Hello, and happy September!

Diving right in, this newsletter involves an Ask and an Essay. Thank you in advance for considering the former and reading the latter.

The Ask

The Ask, part 1:

If you live in the Greater Tetons Region – whether full- or part-time – please follow this link to fill out the public opinion survey I am conducting. (Alternatively, you can also access the survey by scanning the QR code below.)

https://research-polls.com/sIwr

The Ask, part 2:

Please share the link with others. My goal is to get as many responses as possible before the survey closes on September 22.

The Why

Over the past year or so, I’ve heard a lot of concerns about where Jackson Hole and, more broadly, the Greater Tetons Region is headed.

How widespread are such perceptions? Rather than speculate, I developed and commissioned a survey to gauge residents’ views about the area and its future.

Gathering responses involves two phases.

Phase 1 just wrapped up. It was a random, statistically valid telephone survey of the region’s residents. (For the survey, I defined the Greater Tetons Region as Jackson Hole, Star Valley, and Teton County, ID.)

To get the broadest possible sense of residents’ attitudes, I’m launching Phase 2 – an all-are-welcome on-line version of the same survey. To take it, please click HERE.

As noted, my goal is to get as many residents as possible to complete the survey (it’s available in both English and Spanish). Hence the Ask.

The on-line survey runs from September 5-22, and I’ll present the initial findings at the September 23 kickoff conference for the Teton Leadership Center. It promises to be a great event, and you can register by clicking HERE.

I’ll also write about the survey’s findings in a future CoThive newsletter.

The Essay

Last month’s Republican presidential debate reminded me anew of how much I dislike election debates.

Local, state, or national, it’s all the same – in my view, debates offer little of value for anyone involved except, perhaps, the media and political professionals.

Why? Because debates reward behaviors and qualities which, at best, are unrelated to good governance. At worst, debates reward behaviors and qualities which are antithetical to good governance.

In this, debates distill the huge and growing disconnect between the qualities needed to be a successful candidate and the qualities needed to successfully govern. The result? Governing bodies filled with people who are great at getting elected, but awful at performing the job they were elected to do.

Why is this so and what might we do differently? I explore these questions in the essay below.

One Other Ask

Much of the funding for the work Charture does – this newsletter for example, or the public opinion survey I hope you’ll fill out – comes from charitable donations.

In Jackson Hole, it’s currently charitable giving season; specifically, it’s Old Bill’s Fun Run season.

For those of you not familiar with Old Bill’s, in 1997 a wealthy Jackson Hole couple partnered with the Community Foundation of Jackson Hole to create one of the nation’s most innovative non-profit fundraisers. Since then, it has raised over $228 million to support local non-profits, an average of over $8.8 million/year to help make Jackson Hole a better place for everyone.

Every Jackson Hole non-profit is eligible to participate in Old Bill’s Fun Run, and every dollar they raise up to $30,000 is matched by Old Bill’s donors (the match is usually around 50%).

Old Bill’s funding is vital to Charture’s operations. If you value this newsletter and our other work, please donate to Charture through this year’s Old Bill’s Fun Run by clicking HERE.

As always, deepest thanks for your interest and support.

Cheers!

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

PS – Please be sure to take our public opinion survey by clicking HERE or scanning the QR code below. Please also encourage everyone you know to do the same.

PPS – Please donate to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run by clicking HERE.

Scan this code to link to our survey. Let us know how you feel about the Greater Tetons Area and its future

The Great Campaign/Governance Paradox

“As the playoff race heats up heading into September, major league baseball has done the impossible: It has rescued itself from irrelevance — not through luck, but by identifying what was wrong about the way it was operating and having the guts to make fundamental changes.

“… If 147-year-old major league baseball can rewrite its rules to address its existential challenges, then maybe there’s hope that this even older and even more rule-bound country can do the same for issues with far bigger stakes.”

– Bryan Walsh; What America can learn from baseball (yes, baseball); Vox Magazine; September 1, 2023

Here’s my dream: We can have better government.

I say this as someone who has spent nearly half of the last three decades serving as a local elected official: 8+ years on the board of St. John’s Health; 4+ years on the Jackson Town Council.

From this perch, I’ve come to believe a fundamental problem – perhaps the fundamental problem – with government at all levels is not who we elect, but how we elect them. In other words, our governance system is a mess because our hiring process is a mess – particularly at the state and federal levels.

In a nutshell, here’s the problem.

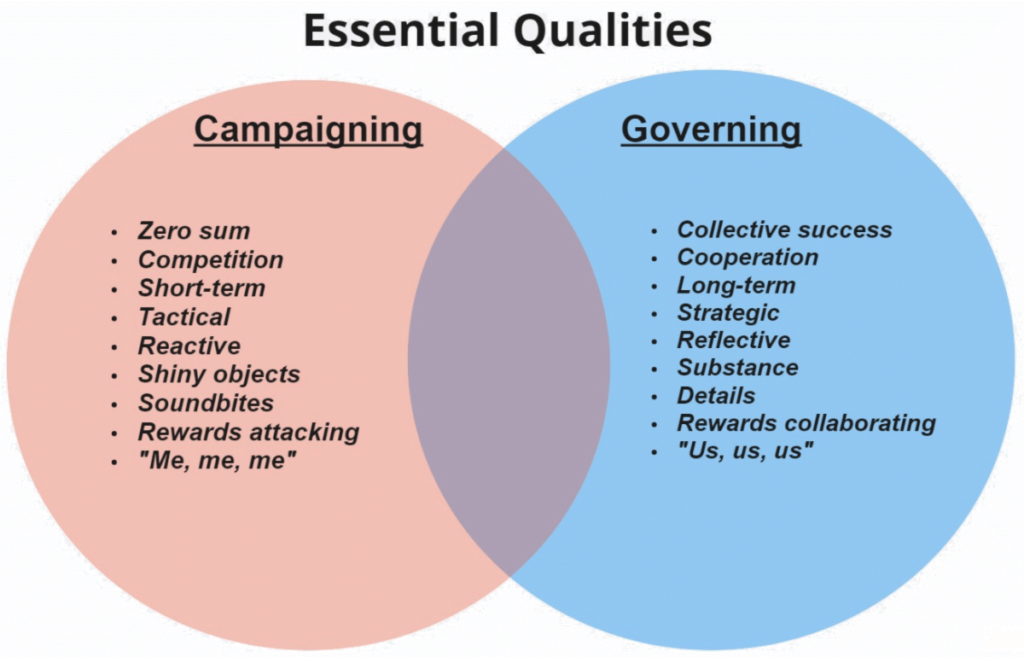

- The skills discrepancy

- Being an effective candidate for office requires a certain set of skills.

- Being an effective elected official requires a different set of skills.

- Unfortunately, the skills you need to be an effective candidate arguably harm your ability to be an effective elected official, and vice-versa.

- The consequences

- Our elections identify and reward people who are good at running for office. What they do not do is identify and reward people who can actually govern.

- As a result, we end up with governing bodies stocked with people who can’t or won’t govern, creating governing bodies that don’t work well.

- Bonus observation: all of this is made dramatically worse by the current media environment – especially social media.

Context

I hold two firm beliefs about our community, nation, and planet.

First, we as a species can be no healthier than our ecosystems.

Second, we as a society can be no healthier than our institutions.

These two beliefs frame my professional and political careers. In both, my ultimate goals are to help us preserve and protect our area’s ecosystem, and to ensure well-functioning institutions.

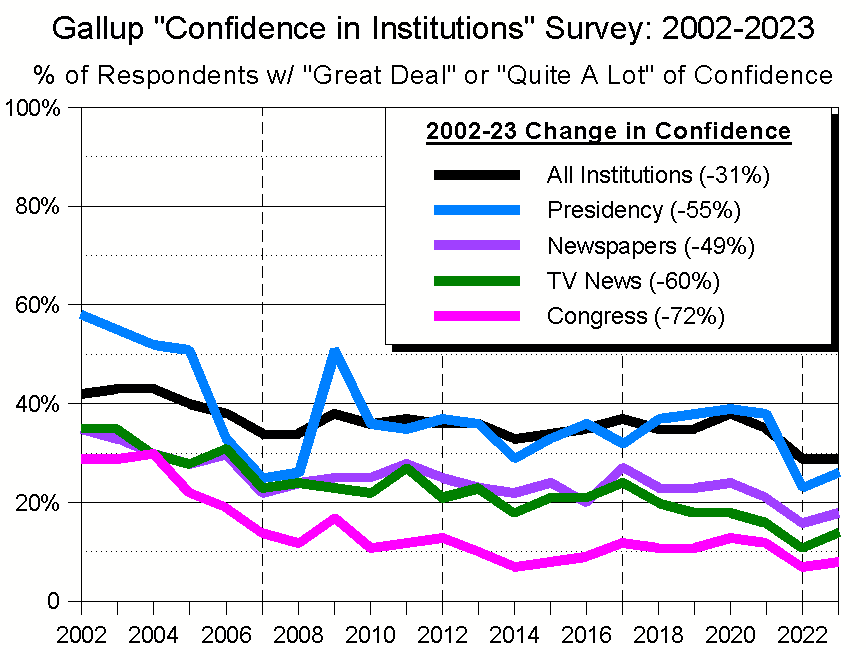

In this context, it’s been disheartening to see – heck, it’s been disheartening to live through – the steady erosion of faith in our institutions. And not just government. Every year, Gallup asks Americans about their confidence in institutions ranging from the federal government to organized religion; from big business to public schools. Since peaking in the early 2000s (around the time of 9/11), Americans’ confidence has declined in every institution in Gallup’s survey.

Most strikingly, between 2002-2023 the four institutions experiencing the biggest drops in confidence were:

- Newspapers (a 49% drop during that time, down to 18%)

- the Presidency (a 55% drop, down to 26%);

- TV news (a 60% drop, down to 14%); and

- Congress (a 72% drop, down to 8%)

To me, the four are inextricably linked through the process of how we elect people to office.

Running v. serving

Running for office and being in office are very different worlds. For example, how does each define success?

In elections, that’s clear: Success equals winning. It’s an easy metric. It’s also a metric which – like that of a baseball game – can be easily understood and endlessly evaluated both before and after the event. And just like sports, campaigns are perfect fodder for all flavors of media – conventional and social.

Also like any sport, running for office is a zero-sum game: Either I win or you do. Therefore, my job is to get a whole bunch of people – few of whom actually know me – to either vote for me or, as importantly, to vote against you.

How do I do that? By drawing attention to myself through soundbites. Controversy. Hot-button assertions. Attacks on my opponent. Focusing on bright shiny objects. Emphasizing noise over signal. A host of stuff perfectly aligned with social media.

Some people are very good at these things. In politics, we increasingly reward them by electing them to office.

What about when you win? What is success for those in office? Defining that is much murkier. If it’s passing legislation, that requires a very different set of skills than winning an election.

In particular, while the goal in both elections and passing legislation is to get 50%+1 of the votes, the two different goals require two very different paths. For example, to succeed in elections many candidates opt to attack their foes. Try that when you’re in office, though, and all you’ll do is alienate someone whose vote you need.

Similarly, elections place a premium on playing a short-term, tactical game. In contrast, success in governance requires long-term thinking, for the legislative process is anything but quick. Further, as that long-term process plays out, you need to keep your eye on the prize, even if that means not drawing attention to yourself.

The list goes on and on, and it results in the great paradox of our system of governance: If I act in a campaign as I must act to succeed as an elected official, I probably won’t get elected in the first place.

The problem

The great campaign/governance paradox is perfectly distilled in our political debates.

For example, consider last month’s shout-fest between eight Republican presidential candidates. The event rewarded those candidates who preened for the cameras and studio audience, talked over the other participants, threw out zingers and soundbites, and generally did whatever they could to attract attention to themselves and/or make their opponents look bad.

What spoils did the victors enjoy? Media attention. The media lapped it up because, as with sporting events, dissecting debates and campaigns is an easy way to fill up space and generate buzz. The political class likes it too, because their job is to provide succor to candidates who, during campaigns, are among the most profoundly insecure people in the world.

Where debates fail – and fail hugely – is in serving democracy. In serving the governance process. In serving you and me. What those two hours of debate did not do is give us any sense of whether the candidates could actually govern. Could actually make government work. Could do anything to make society work.

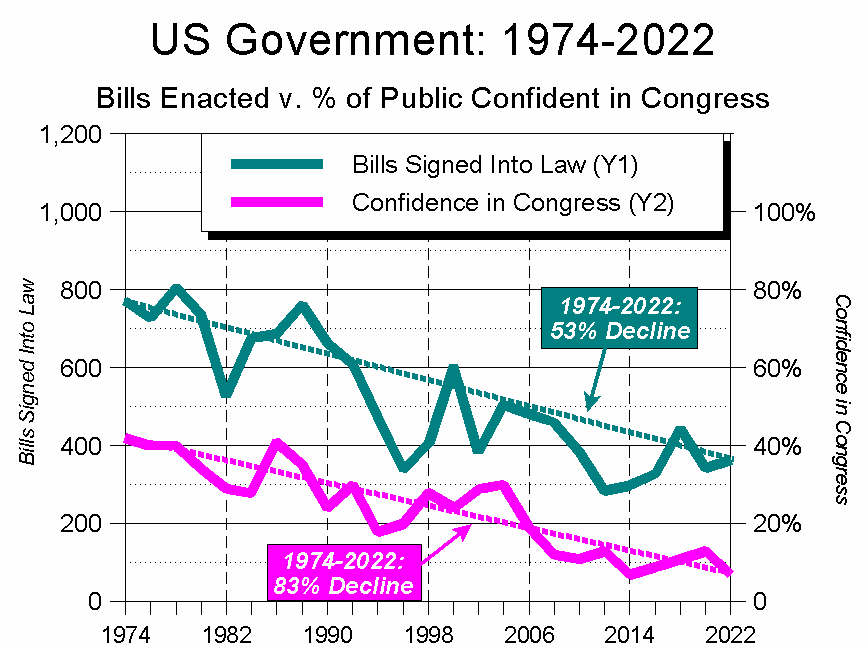

On a larger level, the same is true of campaigns in general. In that vein, what really worries me is the growing body of evidence suggesting that, at all levels of government, we are electing people who are tremendous at running – tremendous at drawing attention to themselves by saying outlandish things, hurling scurrilous charges, and otherwise ginning up controversy – but have no interest in actually governing.

Hence, if they win, what do they do? Keep campaigning. And what do they not do? Govern.

This is governance as Kabuki, a stylized performance whose purpose is not actual governance, but getting re-elected. Our political system rewards not the abstractness of governance, but the concrete reality of elections. As a result, for that growing number of folks whose primary goal is getting re-elected, they find that the best use of their time in office is not to govern, but to basically keep the campaign going. It’s less work, less risk, draws more attention, and has a much bigger pay-off.

Unfortunately, as more elected officials take a transactional approach to office and prioritize their interests over those of the governing body, society pays the price of an increasingly dysfunctional government. The net result? A steady decline in the confidence people have in their government. Which, of course, only makes it that much easier to run against the system. And so the downwards spiral builds upon itself.

A partial solution

So what to do?

The essence of my suggested change is to do all we can to make campaigns focus on the job we actually elect officials to do: govern.

It’s pretty simple, actually. Let’s do all we can to highlight candidates’ governance-oriented skills while working equally hard to reject things that don’t matter to the governance process.

Sadly, on a national level, we can’t do much. Locally, though, we have two levers for making change.

Lever 1: Candidate Debates

Debates are one of the rituals of local campaigns. Candidates face a panel of reporters and are asked questions about things the media think are important. While such questions tell us a lot about local media’s priorities, for two reasons they rarely shine any light on candidates’ ability to govern.

Reason one is the nature of issues. For the most part the issues raised in debates are either essentially unsolvable – think housing or traffic – or ephemeral: e.g., last fall’s non-issue of “Save the Fairgrounds.” As a result, during debates candidates tend to end up sounding pretty much the same.

Reason two is that, because they come and go, issues are not really what matters. Instead, over the course of a term in office, what really matters is an official’s ability to effectively address the issues that arise.

To that end, we should be asking candidates not what they care about, but whether they understand how government works. Not how they would address a particular issue, but how they would get their colleagues to support their proposed solution. Because if they can’t get a majority of their colleagues to vote with them, nothing will get done.

As an alternative to the current system, my suggestion is to conduct what I call the “Free Market Debates.” By this I mean that organizers should devote most of a debate’s time to letting candidates talk about whatever they think is important. Don’t ask candidates about issues. Instead, ask them what they feel is important for voters to know and let them rip. Or blather. Or whatever they might do.

What the candidates say and, critically, what they don’t say will give voters far more insight into the candidates than anodyne responses to questions about intractable issues.

In the same way that all markets need some structure, though, Free Market Debates should not be entirely free form. Instead, specific questions should be asked about candidates’ understanding of the governance process, their governance experience, and their ability to get things done within the system.

We should also tell the candidates well in advance what the agenda will be. Why? Because the kinds of surprise questions that make debates feel like game shows have zero connection to governance.

The game show-cum-sporting event approach to debates emphasizes surprise questions because they add drama and intrigue to the spectacle. But do you know what governance rarely involves? Surprise. Drama. Intrigue. Instead, for the most part governance involves studying lengthy reports well in advance of a meeting, asking detailed questions, and being willing to wait if it’s too soon to make a decision.

Dull stuff, but this slow, plodding process is the warp-and-woof of governance. And what’s not required to succeed in this dull environment – in fact, what works against succeeding in this slow, plodding process – is the ability to quickly come up with sound bites, zingers, and glib responses.

So why structure debates in ways completely unrelated to governance? Elected officials know well in advance what issues they’ll be hearing. Let’s have our debates reflect that reality.

Lever 2: Candidate profiles

The second lever is basically a print version of the first.

Currently, during debates reporters ask candidates about issues the media think are important. Newspaper and web-based candidate profiles do the same. Because issues are usually complex, and because space is usually limited, the almost-inevitable result is that candidates provide answers which make them all sound pretty much the same. Worse, the questions posed never ask about a candidate’s understanding of the job, nor their ability to govern.

Instead, let’s structure candidate profiles so that candidates use the space to identify their priorities. Let’s also ask the candidates what they know about governance and the realities of the job. This will allow voters to focus on who will make a good elected official and not just a good candidate.

Conclusion

We can’t change human nature. As a result, candidates will continue to attack each other, raise phony issues, and otherwise continue to do all the other things that make campaigns so painful for candidates and voters alike.

We also can’t change the national political system. As a result of that, we will continue to suffer through our current– and thoroughly dreadful – politics as game show/sporting event approach to elections.

Locally, though, I believe we can do better. Know we must do better. Just like baseball, we know the problems. And just like baseball, we can find the guts to change. For the same basic reason – it’s the right thing to do to save an institution we so desperately need.