Jonathan Schechter – February 2021

Introduction

In 2020, Teton County, Wyoming was home to an estimated 9,100 households. It also had 1,559 households on the Jackson/Teton County Housing Department’s affordable housing unit wait list. Of those, 1,388 – 89% – currently live in Teton County.

Do the math, and 15% of Teton County’s households – more than one in seven – were on the affordable housing waiting list. Another 2% want to move from surrounding counties to Jackson Hole.

So what’s being done to address the situation?

Well, in 2020 the Town of Jackson and Teton County allocated $2 million – 3% of their combined general operating funds – to support the Housing Department’s affordable housing efforts.

Had that $2 million been used on 2020’s open market, it would have bought:

- 3/4 of one median-priced single family home; or

- 2.4 median-priced condominiums; or

- 2.8 lowest-priced single family homes (assuming 2.8 had been available at that price); or

- 6.1 lowest-priced condominiums (ditto).

Do some more math, and at best, that $2 million could have helped 0.4% of all the families on the Housing Department’s wait list.

Put another way, had it been spent on the open market, 3% of local government’s combined general revenues would have, at best, addressed 0.4% of the community’s affordable housing need. And while free market housing isn’t 100% linked to the community’s affordable housing efforts, the underlying fundamentals are close enough to make it clear that the $2 million/year is not nearly enough to even mildly dent the demand for affordable housing.

In short, Jackson Hole’s current approach to the community’s affordable housing situation is not working. More succinctly, it’s broken.

The current approach to addressing the community’s affordable housing situation arose because the free market approach was failing – it’s far more profitable to build higher-end homes, so that’s what the market does. That was true in the early 1990s when the community’s first affordable housing efforts got going, and it remains true today.

When this reality first became a problem, the community initiated a two-pronged alternative to its long-standing, purely free-market approach to providing housing. One prong was institutional: first with the founding of the Jackson Hole Community Housing Trust, and later with Habitat for Humanity and what is now the Jackson/Teton County Housing Department. The other prong was through government policies. Some offered a carrot to build affordable housing; others brandished a stick.

Big picture, these efforts have been successful – today there are over 1,000 affordable housing units in Teton County. However, the same market forces that inspired those efforts three decades ago are today increasingly hampering their effectiveness – there is so little land in Jackson Hole and so much money to be made building higher-end homes that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to build local affordable housing. Last year, that difficulty reached unprecedented levels.

In 2020, there was such strong demand for Jackson Hole housing that the median price of a single family home rose 46%, to $2.65 million dollars. The median condominium price rose 27%, to $827,500. Assuming a few mortgage basics – e.g., a 15 year mortgage at current rates, and a 20% downpayment ($530,000 for a home; $165,500 for a condominium) – to afford the median single family home a buyer would have needed to earn around $60,000 per month after taxes. For a condominium, the monthly post-tax nut was $15,000.

This in a county where the median household income was around $90,000 per year – one-eighth that needed for the median home; one-half that needed for the median condominium.

This paper looks at Jackson Hole’s astonishing 2020 real estate boom not as an end in itself, but as a five-alarm indicator that the community is facing some extraordinary challenges. Regarding housing of course. More consequentially, though, to its economy, community character, and way of life.

Local government has a role to play in addressing these challenges, but particularly given Wyoming’s wildly-libertarian approach to governance, local government can do only so much.

Instead, the real estate data suggest the community needs to explore deeply whether current approaches are moving us closer to the future we desire, or moving us further away from that goal.

Critically, the question matters not just to those getting priced out of Jackson Hole’s real estate market, but everyone who has a stake in the community. Run a business here? Who’s going to work for you, and what will you have to pay them? Selling high-end real estate? Who’s going to provide the services your well-heeled clients expect? Care about the ecological health of the region? How can that be preserved in the face of overwhelming pressure to build as much housing as possible? And the list goes on and on…

It’s trite and cliched to say things have reached a tipping point, or that there’s never been a more critical time than now, or what have you. Regarding Jackson Hole’s future, however, I think that’s the case. When you combine 2020’s real estate firestorm with the fact that Jackson Hole sits at the heart of the healthiest largely-intact ecosystem in the lower 48, the pressures are intense, there is little room for error and, critically, there is no road map that shows us how to simultaneously preserve the ecosystem’s health, meet our overwhelming housing needs, support a thriving tourism-based economy, and maintain the community’s character.

This paper proposes a solution, one that may or may not work. What is clear, though, is that powerful economic forces are pushing Jackson Hole and the entire Tetons region in a direction receiving little attention and essentially no formal consideration. It’s also almost certainly a direction few would consciously choose.

If that’s true, and if it’s also true that a problem cannot be properly treated unless it’s accurately diagnosed, then this paper will be a success if it catalyzes a clear and thorough discussion of what is happening to Jackson Hole, where the community is likely headed, and whether that direction is one the community wants for itself and future generations. 1

The Basic Data

In 2020, Jackson Hole sold a record number of properties for a record amount of money. Compared to previous years, it wasn’t even close.

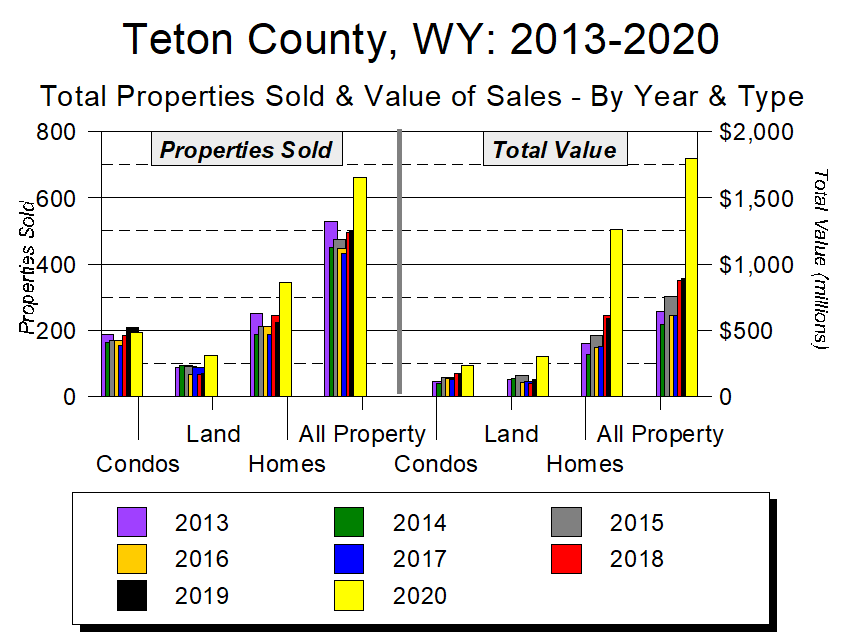

For visually-oriented people, Figure 1 shows what happened.

For those preferring words, here are the key numbers summarizing 2020’s total residential sales: single family homes, condominiums, townhomes, and undeveloped land. All are record-breaking:

- Total number of sales = 662 (up 32% over 2019)

- Total sales amount = $1.8 billion (up 103%)

- Overall median price = $1.59 million (up 45%)

- Overall mean price = $2.54 million (up 53%) 2

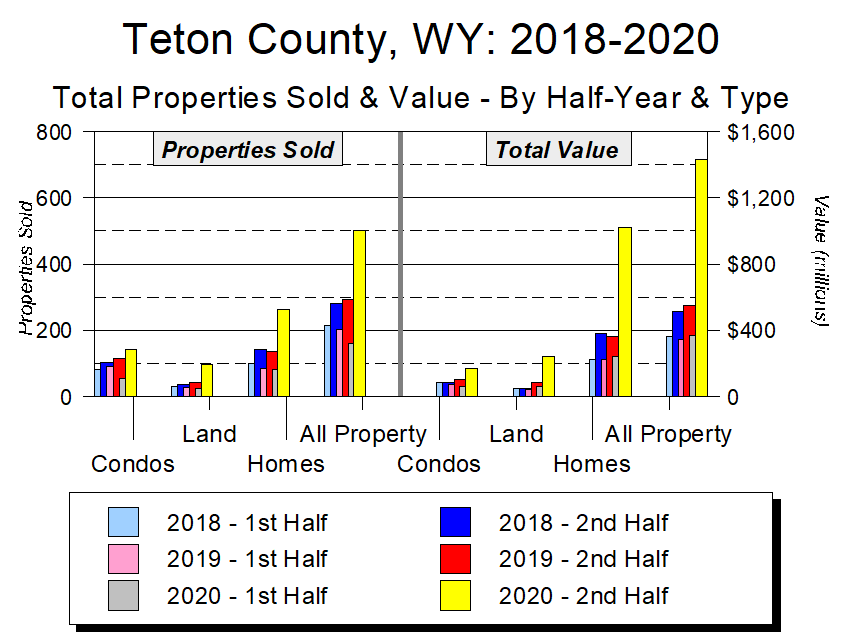

As Figure 2 shows, the first half of 2020 wasn’t anything special. In the second half of the year, though, things exploded – just on their own, many of 2020’s second half numbers alone were so crazy that they far exceeded the annual figures from every previous year:

- Total sales amount

- 2019 total = $947 million

- 2020 2nd half = $1.53 billion (up 61% over 2019’s total)

- Overall median price

- 2019 total = $1.10 million

- 2020 2nd half = $1.67 million (up 52%)

- Overall mean price

- 2019 total = $1.78 million

- 2020 2nd half = $2.87 million (up 61%)

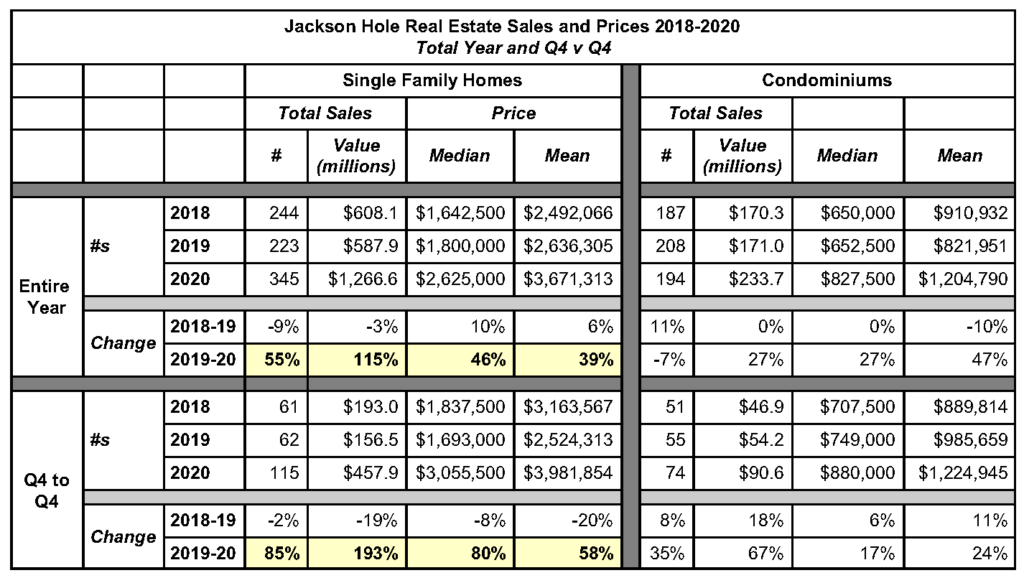

Because the market was relatively flat between 2013-2019, Table 1 focuses on just the past three years, highlighting what happened in Jackson Hole’s residential real estate market since 2018.3

My Big Takeaways

OMG

The numbers are staggering. Big picture, pick any number and it confirms 2020 was an extraordinary year.

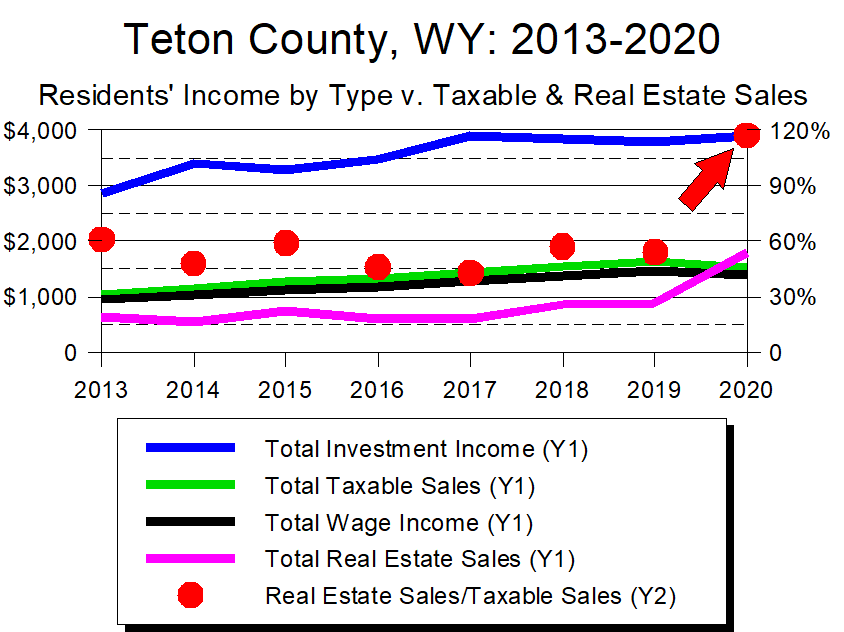

Perhaps the most significant figure is this: In 2020, Jackson Hole’s real estate sales exceeded its taxable sales. That was unprecedented – never before had Teton County’s real estate sales come close to matching its taxable sales. In particular, as Figure 3 shows, before 2020 real estate sales equaled about half of taxable sales. In 2020, they were 17% greater.

Some of this had to do with the COVID-related decline in taxable sales. But even if 2020’s total taxable sales had climbed 10% from 2019, they still wouldn’t have equaled 2020’s real estate sales.

Why does this matter? Because local government doesn’t generate any revenue from real estate sales. Indeed, had real estate sales been taxed at the same rate as, say, a rotisserie chicken sold at a grocery store, those sales would have generated another $108 million for the cash-strapped state, county, and town governments (the total taxes generated by taxable sales were $92 million).

Instead, every penny of that $1.8 billion in real estate sales went untaxed. A sweet deal for the buyers and sellers; arguably not so much for the governments charged with providing the county’s 662 new property owners with a level of service befitting their multi-million dollar investments.

The 2020 sales figures were so big that real estate is now the second-biggest sector of Jackson Hole’s economy, trailing only investment income. With that, Jackson Hole has arguably become the apotheosis of America’s post-industrial economy, a place whose economy is dominated not by labor or production, but instead by the buying and selling of assets.

Something has shifted

In a certain sense, 2020’s real estate explosion wasn’t unexpected because its basic pieces were already in place. These included:

Ease – Rapid technologic advances have made remote working increasingly easy, resulting in a global boom in tele-commuting.

Acceptability – By extension, as remote working has grown increasingly easy, it has also grown increasingly acceptable.

Diminished hardship – The perceived hardships of living in a place as geographically remote as Jackson Hole have increasingly declined thanks to rapid advances in not just technology, but air service, on-line shopping, and the like.

What wasn’t expected was how COVID-19 would catalyze these and other trends, turning the small stream of people who had been moving to Jackson Hole and other “remote” places into a raging river. Critically, though, “raging” is only from the perspective of the towns COVID-refugees are moving to. In larger cities, the comings and goings of that number of people would be too small to have much effect. In smaller towns, though, such an influx can profoundly influence community character.

The not-a-bubble bubble

Given the huge jump in prices, it’s easy to view Jackson Hole real estate as a bubble. It’s almost certainly not, though.

A bubble is created when asset prices become disconnected from economic fundamentals. Arguably that’s what happened to Jackson Hole real estate in 2020 – the thoughtful real estate agents I know (insert your Realtor joke here) are at least a bit appalled by the run-up in prices, feeling properties are currently selling for far more than they’re worth.

Certainly that’s true by, say, 2019’s standards, or even mid-2020’s. But what if there’s a new reality? What if something fundamental shifted in the second half of 2020? If that’s the case, then what we’re experiencing isn’t a bubble but a ratcheting up.

Which I think is the case, because of the most fundamental of economic fundamentals: supply and demand. In particular, prices will likely stay around their new, elevated level because, when it comes to Jackson Hole real estate, there is far more demand than supply.

This has been true forever, of course, but until recently demand was tempered by Jackson Hole’s geographic isolation. In the last few years, though, rapid improvements in technology and logistics PLUS an increasing acceptance of remote work PLUS an economy increasingly geared toward remote work PLUS the convenience of great air service (commercial and private, passenger and freight) PLUS Jackson Hole’s new-found hipness PLUS other factors too numerous to mention have combined to neutralize most of the “I’d love to live there but it’s just too remote” objections keeping growth at bay. As a result, there is now essentially unlimited demand for the very limited supply of Jackson Hole housing.

Will prices come down? Sure. At some point. To some degree. Especially if, post-COVID, some pandemic refugees find that living in a remote corner of Wyoming isn’t their cup of tea.

But to use atomic physics as a metaphor, my sense is that, in 2020, Jackson Hole real estate became so energized that prices jumped up an electron shell or two, and will never fall back to their previous, lower level (barring, of course, some titanic economic and societal collapse). As a result, future fluctuations will take place not, say, between the median home prices of 2015 and 2020 ($1.3 million and $2.6 million respectively), but within the boundaries of the new, higher-priced 2020 range.

Policy Considerations

Property taxes and rents

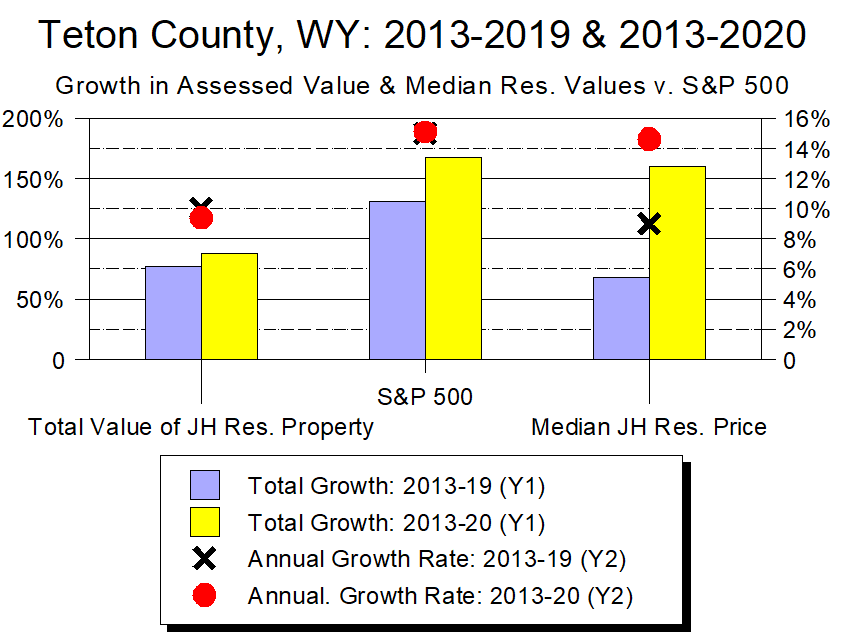

The real estate sales database I’m working with lists nearly all the residential sales that occurred in the Jackson Hole valley between 2013 and 2020. Figure 4 compares the growth rates of Jackson Hole’s median residential prices to two other economic indicators:

- the Standard & Poors 500 Index of stocks (S&P 500) and

- the total assessed value of Teton County’s residential properties.

The growth rates are shown for two time periods: 2013-2019 and, adding one year, 2013-2020. What’s striking is this.

For both Teton County’s overall assessed value and the S&P 500, there was little difference between the 2013-2019 and 2013-2020 growth rates. Which makes sense – it’s hard for just one year to affect a multiple-year growth rate.

Hard, but not impossible. Case in point: In 2020, Jackson Hole’s median residence price grew so much that, all by itself, it boosted 2013-2019’s compounded average annual growth rate of 9.0% to 2013-2020’s rate of 14.6%.

One mammoth year. One mammoth increase in the long-term growth rate.

Why mention this? Because the county’s property value assessments are based upon real estate sales prices. And because last year was so extraordinary, over the next one-to-two years 2020’s real estate boom is going to cause Teton County’s assessed property values to soar. Which, in turn, will likely lead to property tax increases.

For the people purchasing new Jackson Hole properties, this won’t be much of a problem, for Teton County’s property tax rates are very low by national standards.

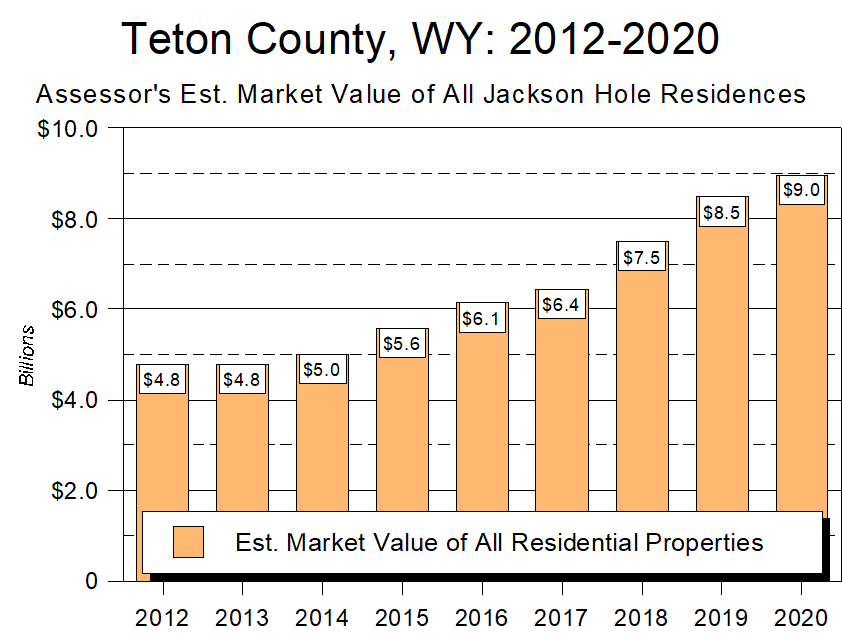

For people struggling to earn enough to live in Jackson Hole, however – which these days means pretty much anyone without significant investment income and/or outside sources of income – the property tax increase resulting from 2020’s real estate deluge is going to come on top of several previous years of significant increases, adding to the financial challenge of living in Jackson Hole. (Figure 5)

Unfortunately, the same will be true for renters, for both increasing property values and increasing property taxes invariably lead to rent hikes. Over the past few years, the combination of increased property values and increased property taxes have resulted in many sharp increases in rents, and 2020’s housing price explosion will likely keep this pattern going for at least the next few years.

Employees, employers, and workforce housing

Here are two basic facts about the Jackson Hole housing market.

First, in 2020, you could not make enough from local wages alone to afford a Jackson Hole single family home. Instead, you had to meet at least one of three additional criteria:

- have tremendous accumulated wealth; and/or

- make a lot of money from investments; and/or

- have significant support from family or other sources.

Some folks might have been able to swing a median-priced Jackson Hole condominium on local wage income alone, but even there it was difficult – not many Tetons jobs pay $175,000/year after taxes.

Second, the disconnect between Jackson Hole’s tourism economy and its housing situation is the apotheosis of the disconnect between Jackson Hole’s 20th century operating system and its 21st century reality, a disconnect growing greater by the year.

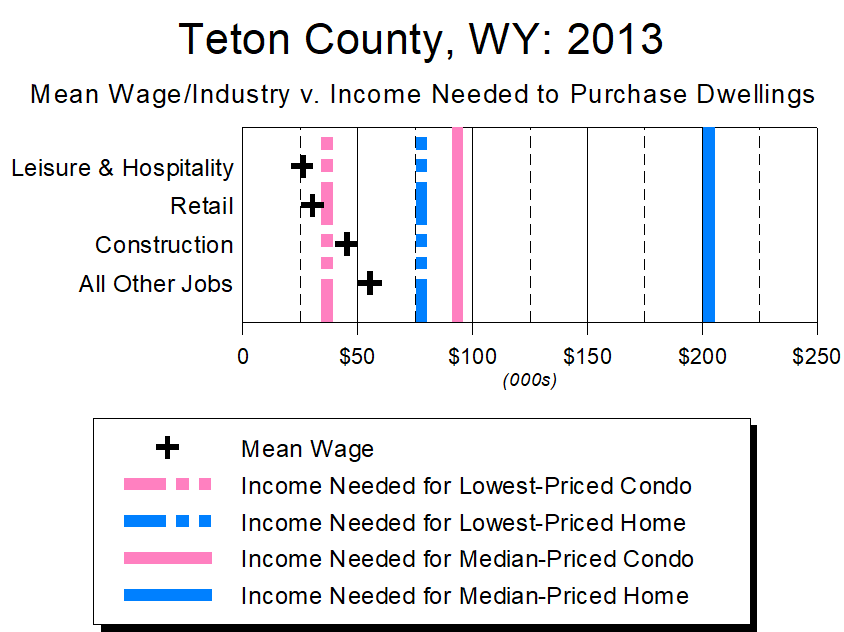

As many people know, on a per capita basis, Teton County is the wealthiest county in the wealthiest country in history of the world. Less well-known but equally true is that Teton County ranks in the top 10 of all American counties in its proportion of tourism-related jobs; i.e., jobs in lodging, recreation, and restaurants. Throw in retail and construction, and these core Jackson Hole industries account for nearly 60 percent of the community’s jobs.

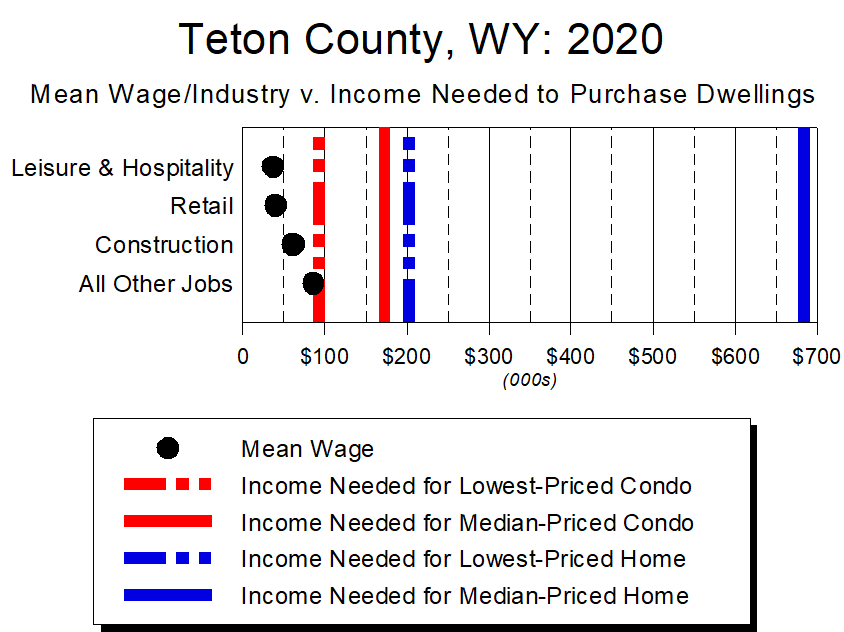

Yet because the business model of both tourism and retail is to hire a large number of employees and pay them relatively little, these core industries plus construction account for only around 40% of the Teton County’s overall wages. As a result, in 2020, the collective mean annual wage for Teton County’s nearly-11,000 tourism, retail, and construction jobs was around $43,000, while the collective mean annual wage for the county’s 8,200 other jobs was around $86,000; i.e., twice as much.

Neither figure was anywhere close to the income needed to afford to buy a free-market median Jackson Hole condominium, though, much less a median single family home.

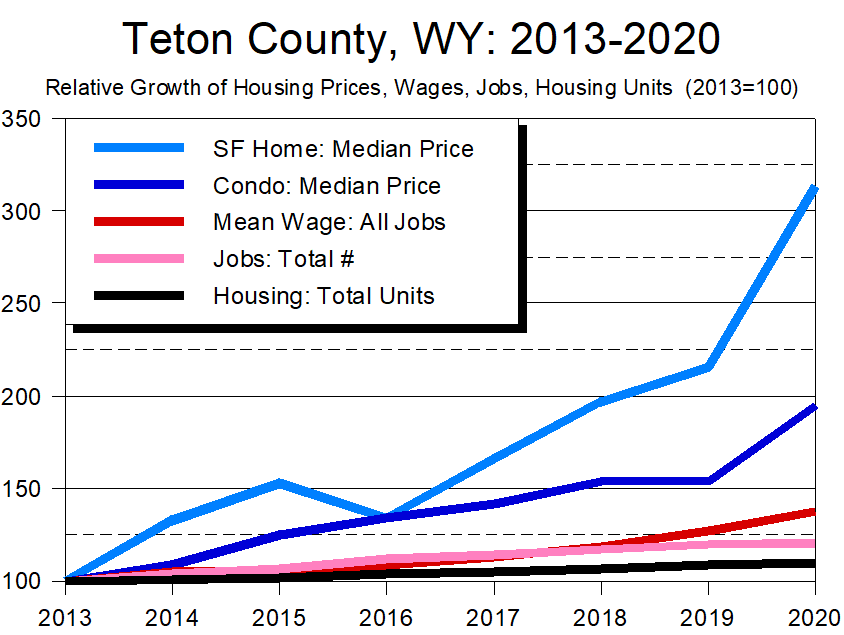

Affording a Jackson Hole home on a Jackson Hole wage has always been a stretch – the last time the median Jackson Hole home was affordable to someone earning the median Jackson Hole wage was in the mid-1980s; i.e., a generation ago. As Figure 6 shows, though, as recently as 2013 someone relying on a non-tourism wage could at least hope to buy something.

Not any longer.

In 2020, home prices grew so rapidly that, with the exception of only one industry – finance – none of Teton County’s industries paid its employees a mean wage high enough to allow them to afford even the cheapest condo on the market. And even for those working in finance, the mean wage could barely afford it. (Figure 7)

It’s also worth noting that, to put it mildly, finance is not a profession that evokes the “Last of the Old West” brand we pride ourselves on and market to the world…

In fact, in 2020 home prices became so disconnected with local wages that if employers in Jackson Hole’s core industries (tourism, retail, and construction) had wanted to pay their workers enough to afford the median-priced Jackson Hole condominium, they would have needed to quadruple their mean wage. Employers in non-core industries would have needed to double theirs.

And single family homes? To afford the median-priced Jackson Hole single family home, core industry employers would have needed to increase their mean wage sixteen-fold, while other employers an average of “only” eight-fold.

Which, of course, is madness. Tourism’s “hire many/pay little” business model works well when there’s ample, inexpensive housing available. When there’s not, though, any community with a thriving tourism economy will face the same workforce housing problem now affecting Jackson Hole.

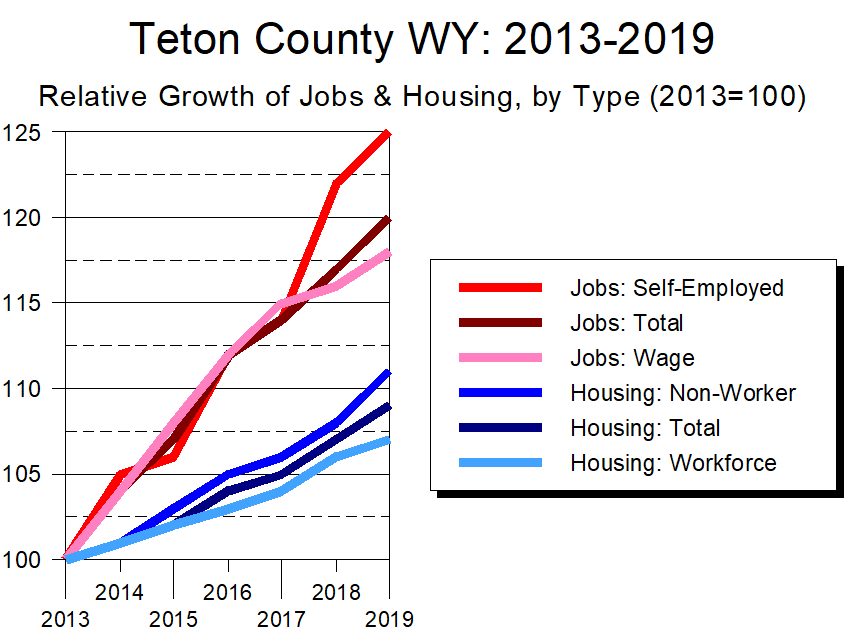

Even before COVID struck, Jackson Hole’s workforce housing problem was becoming increasingly acute. Two reasons underlay this: the number of jobs was growing faster than the county’s housing stock; and an estimated half of all the housing being built was targeted at people not in the local workforce; e.g., second home owners, retirees, and remote workers. (Figure 8) And as with so much else relating to current Jackson Hole’s socio-economic convulsions, COVID-19 amplified these issues.

Making Jackson Hole’s situation more complicated still are two additional challenges.

One is the region’s growing attractiveness to tourists – both summer and winter, and especially high end. More tourists create more business opportunities and, by extension, the need for more employees, especially because high-end tourism is often quite labor-intensive.

The other challenge is local government’s extraordinary dependence on the sales taxes generated by tourism. More tourism creates more revenues for local government, but also comes with a cost, including the need for more labor. Begging the question, “Where will all these additional employees live?”

Combine these problems with the rapidly-deteriorating workforce housing situation, and the result is captured in Figure 9: Teton County’s housing growth is trailing job growth, which is trailing wage growth, which is being eclipsed by the rapid growth in housing prices, which in turn is being driven by extraordinary outside demand.

Unfortunately, while this conjunction of problems is taking its biggest toll on the tourism sector, tourism is not alone in bearing these the problems. Not by a long shot.

Instead, think of tourism as Jackson Hole’s canary in a coal mine. Due to its size and structure, tourism is the local industry most sensitive to whatever socio-economic stresses the community is facing at a given time. Currently, those stresses include affordable housing, the challenges posed by last summer’s onslaught of visitors (an onslaught likely to be repeated in summer 2021), and of course COVID-19’s disruptions. All of this and more may be most-visibly washing over tourism right now, but each of the problems facing tourism will eventually manifest themselves in the community’s other sectors and facets.

Love it or loathe it, the reality is that tourism is integral to the fabric of the Tetons region, affecting everything from ecosystem stewardship to the big-city amenities enjoyed by the small town that is Jackson Hole. Some of this is clearly positive, some of it negative, and most of it a mix. What’s been striking for several decades, though, is that the overall system has generally been in balance, with things basically working for nearly everybody: residents and tourists; employers and employees; the public and private sectors.

The challenge now is that the changes currently sweeping over the community are so rapid and so profound that they are disrupting this long-running stasis. Remote workers are increasingly competing with those in tourism. Recreationists with conservationists. Tourists’ desires with those of locals. And the list goes on…

All of these challenges flow from the community’s historical reliance on tourism and how that industry has evolved. And because few aspects of life in the Tetons region are more than a degree or two of separation removed from tourism, the upheaval of the past year will eventually touch most aspects of the region’s socio-economics.

The all-encompassing challenge

Given the extraordinary disconnect between the demand for Jackson Hole real estate, what that real estate costs, and what local employers can afford to pay, we’re deluding ourselves if we think our current approach to affordable housing is going to address our issues. And the operative word is our.

This past summer shone a light on how difficult things will become for our tourism industry if employers can’t find enough employees. But it’s not just tourism. Like the interconnected roots of an aspen grove, the socio-economic matrix binding the greater Tetons region together means that problems in one area will inevitably manifest themselves elsewhere.

Including, critically, the non-human world, for Jackson Hole’s increasing number of tourists threatens to overwhelm our ecosystem, putting at risk the region’s economy and community character.

On the positive side of the ledger, within the next year or so COVID-related pressures will settle down, and things will not feel as crazy. But that relative calmness won’t alter the fact that, thanks to 2020’s extraordinary real estate boom, Jackson Hole’s new normal – one driven by our extraordinary supply/demand imbalance – threatens to overwhelm us: economically, socially, and ecologically.

So what do we do?

Let’s start with housing. Three decades’ worth of affordable housing efforts have created a variety of categories and definitions, but for simplicity’s sake, let’s divide the local housing world into two categories:

- “Free market housing” which, as a rule of thumb, requires non-wage income to afford; and

- “Community housing,” which is housing that can be afforded on Jackson Hole wages alone.

Despite the fact that there are more than 1,000 deed restricted homes in Teton County – roughly 10% of the entire housing stock – evidence ranging from affordable housing wait lists to the rapid growth of Jackson Hole’s bedroom communities makes it clear that the current approach to addressing the need for community housing is no longer working very well.

Which raises the question: Can it work going forward? Arguably not. Not when jobs are growing more than twice as fast as housing, and when everyone in the housing supply chain is incented to sell, design, build, furnish, and service higher-end homes and their owners.

If the current approach isn’t working, then, how about scrapping it and taking an “unleash the free market” approach? Unfortunately, as history has shown us, there’s no chance that will work.

During the 20th century Jackson Hole relied on the free market to develop all its housing, and the system worked until it didn’t – hence the genesis of the community’s affordable housing efforts. Since then, nothing has really changed except the supply/demand imbalance has become even greater. As a result, an unfettered free market approach to addressing community housing is guaranteed to fail, for every incentive driving the free market invariably leads to only one product: highly profitable high-end homes.

What if we flood the market with lower cost homes? Ignoring the fact that they would need to be massively subsidized, the combination of pent-up local demand plus virtually unlimited external demand means those new homes would quickly be snapped up and just as quickly see their prices skyrocket well past any reasonable definition of “affordable.” Then throw in the fact that Teton County is gaining 800-1,000 jobs/year – few of which pay enough to afford free-market housing – and you have a community housing problem that, if it can be addressed at all, can only be done so by the community working as one.

All of this is brutally challenging. Making things even more so is that the urgency of the housing situation may cause us to lose sight of, or run roughshod over, the thing that makes Jackson Hole unique in all the world: our generally-intact ecosystem.

Simply put, Jackson Hole will never build its way out of its housing problem. But it’s easy to imagine the community so prioritizing housing that we do irreparable harm to our ecosystem. Why? Because that’s what every other desirable place to live on Earth has done. Spin a globe, put your finger down on a cool place to live, and save for our region there’s not one example of a place with both a healthy, intact ecosystem and a successful industrial or post-industrial economy. Not a one. Instead, whether intentionally or unintentionally, every place you can name has sacrificed the health of its surrounding ecosystem to develop a contemporary economy. Every. Last. Place.

Unless we take great, deliberative care to do otherwise, 250 years of precedent suggests ecosystem degradation will be our fate as well. In fact, it’s already happening – despite the fact that 97% of Teton County is public land, we have significantly polluted streams and alarmingly compromised aquifers. Why? Because even in one of the most pristine spots on the planet, ecosystem stewardship cannot be taken for granted.

Which raises the prospect of Jackson Hole falling victim to an incredibly bitter irony: If we prioritize economic growth over ecosystem protection, we’ll end up with neither, for over the long run, our economy can never be healthier than our ecosystem. And because our ecosystem is the region’s wellspring, ultimately the degree to which we degrade our ecosystem will also be the degree to which we degrade our economy and character.

Because the fundamental appeal of the Tetons region is this: People want to visit here, move here, live here not because of our fine dining or interesting stores or other built amenities. All of these are great, but at their core they are no different than other restaurants or stores or amenities found anywhere else in the world.

Except in one key sense: Their clientele is attracted by the region’s ecosystem.

People want to visit here, move here, and live here because there are few other places with our ecosystem’s health. And our real estate prices are booming because there are no other places combining a pristine ecosystem with such a high quality of life. If we choose to prioritize the health of the economy over that of the ecosystem, though, we stand to lose both.

It may be just a coincidence, but today both the region’s ecosystem and its tourism economy are struggling. For different reasons, and in different ways, but struggling nonetheless. For over a century, the community has had the luxury of taking ecosystem health for granted while focusing on economic development. Now, however, the stresses on the economy, environment, and community character suggest the need for a holistic examination of what the community values and how well we’re honoring those values. A key component of that effort needs to focus on community housing.

Solutions

So what to do?

Unfortunately, there are no clear solutions, no extant models we can emulate. The socio-economic challenges we face are ones also facing every other desirable place in the world, but no other place also faces the additional challenge of preserving a generally-intact ecosystem.

Given that there is no widely-accepted “solution” to the problem, here’s my best shot. It’s an eight step process I call “Comfortable Carrying Capacity” (CCC).

- Clearly identify all the critical wildlife habitat, migration routes, and other ecologically important lands in the county.

- Develop and execute a strategy for conserving not just those lands, but a comfortable buffer zone around them (to allow for the proper functioning of ecological processes such as evolution, adaptation to climate change and other pressures, and the like).

- Identify a reasonable capacity for our current road system (for going forward, it’s unlikely that system will change much).

- Evaluate three elements – how much land is not yet developed, how much of that needs to be conserved for ecosystem health, and how much traffic our road system can reasonably handle – to determine how many people can comfortably live in Jackson Hole.

- Once a preliminary population figure is identified, calculate how much land is needed for commercial and other non-residential needs.

- Through an iterative process, refine the number of people who can comfortably live in Jackson Hole while still meeting the community’s other needs.

- Once this number is identified, begin building as much community housing as possible (this assumes the free market will address those not dependent on local wages).

- Actively pursue solid legal, social, and financial relationships with other communities in the region to ensure that the benefits and burdens of future growth are agreed upon and broadly distributed.

Is this approach social engineering? You bet. Will it be fraught with problems? Of course. And does it imply calculating, building toward, and ultimately enforcing a human carrying capacity for the Jackson Hole valley? Yup.

But every other approach to address Jackson Hole’s future has also been fraught with problems, and each – including relying on market forces – also involves some variation of social engineering and implied carrying capacities.

What no other approach has offered, though, is a clear strategy for preserving and protecting the area’s ecosystem. A hope that the ecosystem would be protected? Absolutely. A faith that, in the end, it would all work out well? Of course. But as our impaired streams and compromised aquifers suggest, this faith is not being fully rewarded…

Neither hope nor faith is a strategy, and the evidence clearly suggests that defining and executing a clear, broadly-embraced strategy is the only way we’ll be able to support both a healthy ecosystem and our successful contemporary economy.

For all its problems, the CCC approach offers a way to produce three outcomes other approaches can only hope to achieve, and for which no other approach offers a clear strategy.

Outcome 1: Preserving and protecting the area’s ecosystem. The CCC makes ecosystem health its top priority, and keeps it top of mind in all ways.

Outcome 2: A laser-like focus on developing a diverse housing stock; i.e. one in which most new housing is community housing. With this will come a concomitant focus on maintaining a sense of community.

The current system has produced a lot of workforce housing, but as the data suggest, it’s failing to keep up with the demand. The current approach also highlights the failures of a purely free market approach, for every new free market development of the past couple of decades has focused on the much-more-profitable high-end home sector.

Outcome 3: Achieving a comfortable population, as opposed to an overcrowded one.

Under the current system, the town will become much denser; under an unfettered free market, so too will the county. While that might seem good to people moving to Jackson Hole in the future (“This is much better than what I left behind”), it doesn’t necessarily align with what current locals want. Defining “comfortable” won’t be easy, but without aiming for it, we’ll never get there.

Which is basically the problem with both the current approach and an unfettered free market approach. The former offers sweeping platitudes about the community’s future, but doesn’t convert those platitudes into a solid foundation for action. In contrast, the latter assumes that the result of every individual maximizing his or her self-interest will be the best possible outcome for the whole. That may be true in an Objectivist fantasy world, but in the real world it creates a lot of problems, not least of which is wreaking havoc on ecosystems. And by extension, the communities that rely on those ecosystems.

Preserving and protecting the area’s ecosystem is the lofty and extraordinary goal the Jackson Hole community committed to in its Comprehensive Plan. And the happy news is that good progress has been made toward that goal.

But one unanticipated consequence of that progress is that the community is becoming increasingly desirable. Put another way, the community’s land use regulations and other conservation-related efforts have worked so well that Jackson Hole has become a magnet for not just outdoors enthusiasts, but those with the means to live anywhere in the world. And as those folks choose Jackson Hole in increasing numbers, it’s putting incredible stresses on each of the region’s three pillars of sustainability: economy, community, population, and ecosystem.

How to address the problem isn’t clear. The CCC approach may or may not be the answer, but at a minimum it can get us thinking about addressing a situation that is failing under current approaches.

The larger issue is this. Jackson Hole is facing an extraordinary breadth and depth of challenges. Many are sensed, but few are deeply understood. And little effort has been made to develop a holistic understanding of how they tie together and complement one another.

If they are to be successfully addressed, though, it won’t be enough to topically treat their symptoms. Instead, the community needs to begin by developing a shared understanding of their root causes.

The 2020 real estate sales data make it clear where things are going – a Jackson Hole where only those with gobs of investment income can afford to live, or at least live well. No one wants that, most especially those with gobs of investment income.

This reality provides everyone who cares about Jackson Hole with one shared value. A second shared value is the desire to preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem. Combined, these two shared values can provide a foundation for mutually assessing where we are, deciding where we want to go and, if change is needed, collectively pursuing a future that reflects what the community wants – not just for itself, but for future generations of residents and visitors.

1 A technical note. All the data in this paper are based on sales within the Jackson Hole valley. Sales in Alta, WY are not included. For the purposes of this paper, “condominiums” represents both condominiums and townhomes. “Residences” combines single family homes, condominiums, and townhomes, and “residential properties” includes single family homes, condominiums, townhomes, and undeveloped residential land.

2 “Median” is the mid-point of a series of figures lined up lowest to highest. “Mean” is more commonly known as “average,” and is calculated by adding up all the figures in a data set and dividing the sum by the total number of figures. For example, in the series 4, 5, 6, 12, and 18, the median is 6 (i.e., the one in the middle of the series) and the mean is 9 (4+5+6+12+18 = 45. Divide 45 by the 5 numbers in the set and the result is 9).

3 Table 1 omits residential land sales because acreage varies so widely that mean and median figures make little sense. That noted, in 2020 123 parcels of vacant land sales were sold in Teton County, nearly twice 2019’s total of 69. 2020’s sales totaled $303 million, up 134% from 2019’s total of $130 million. 2020’s median value was $1.2 million and the mean $2.5 million, increases of 6 percent and 31 percent respectively from 2019.