Hello and happy late-February!

Today’s newsletter is based on two recent occurrences.

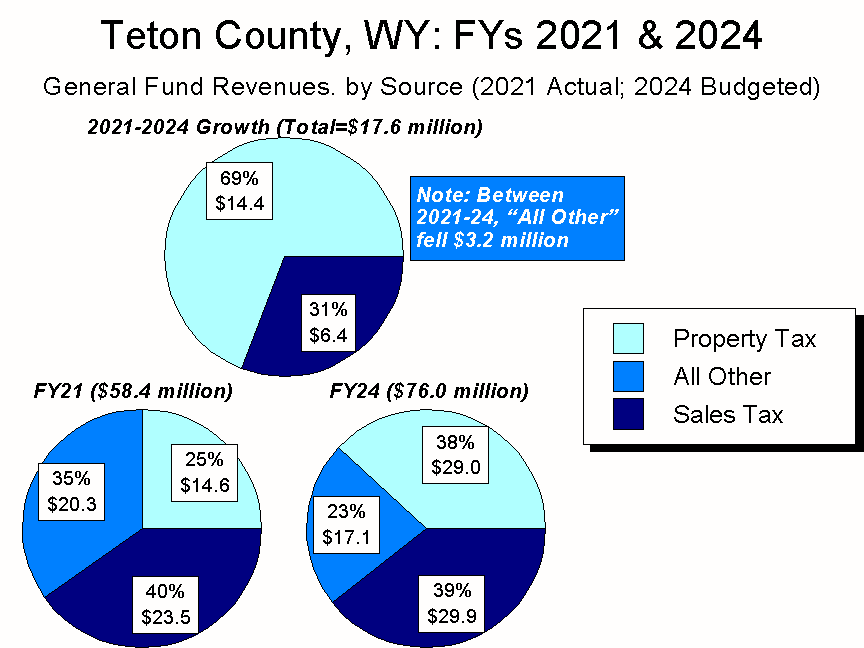

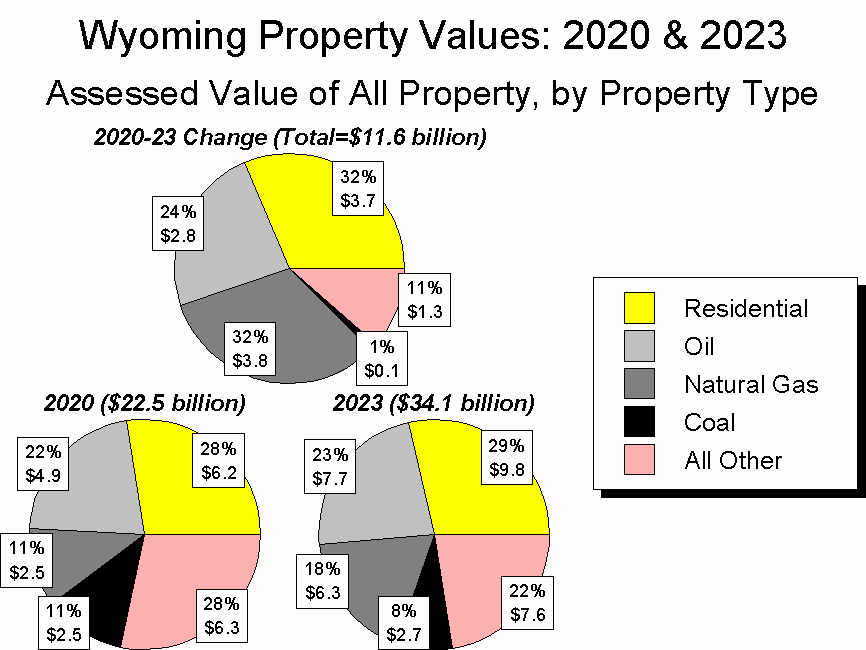

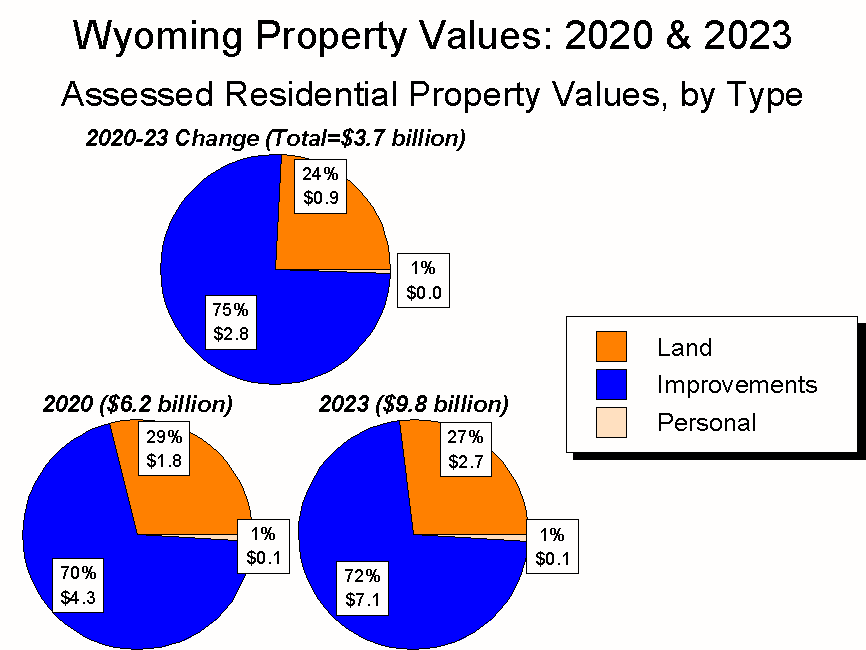

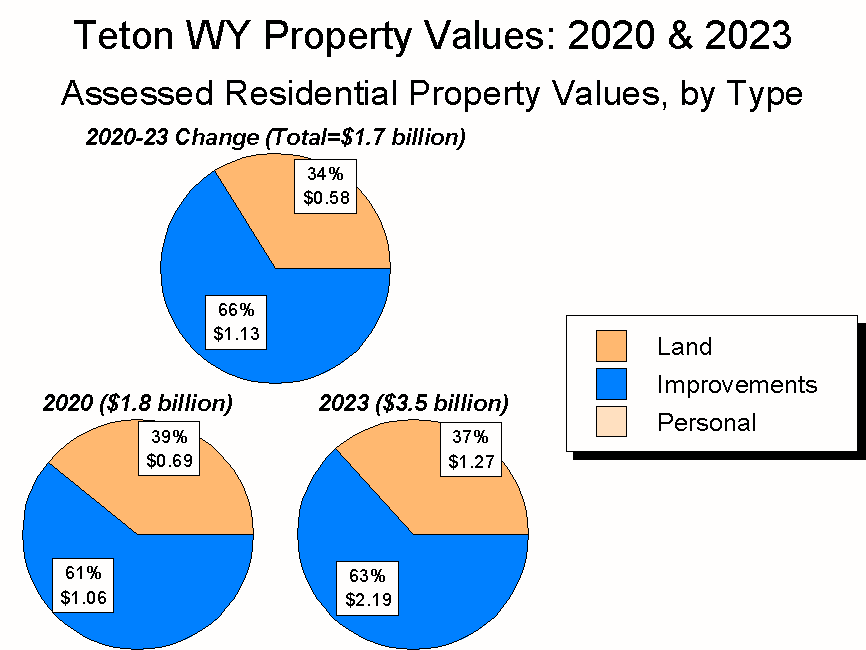

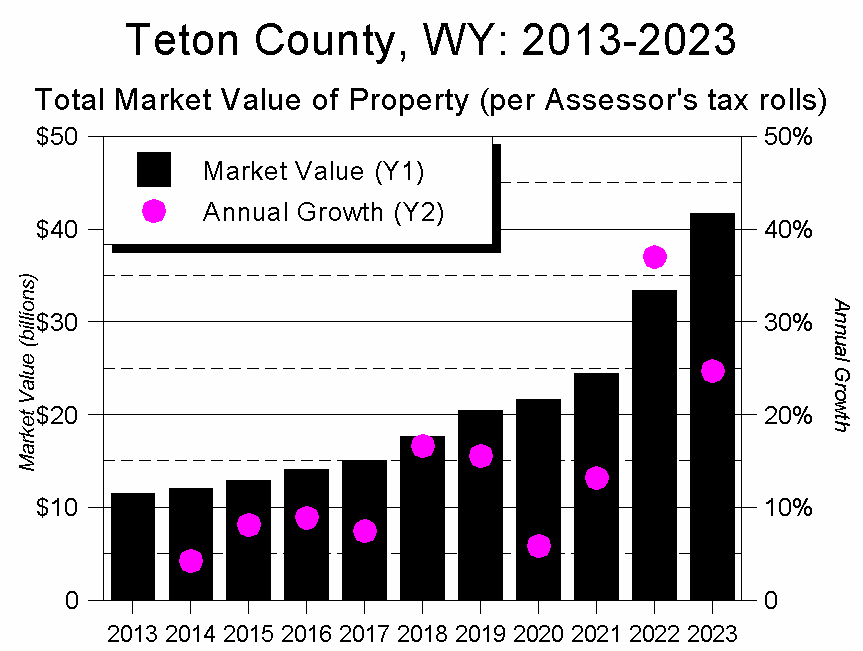

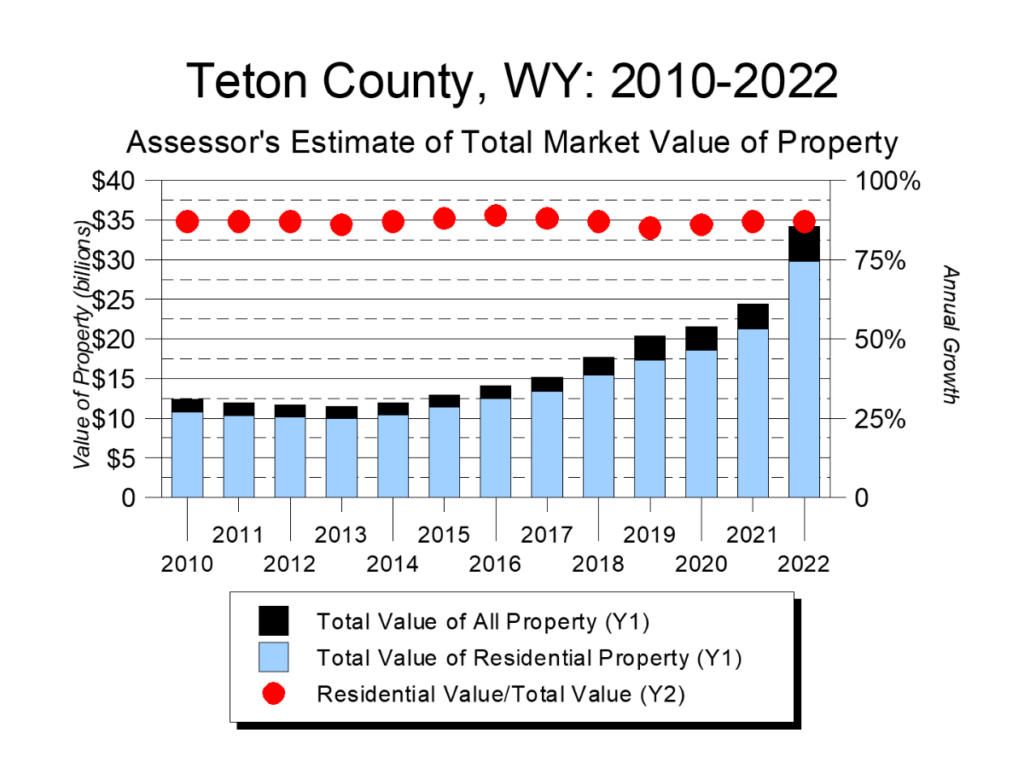

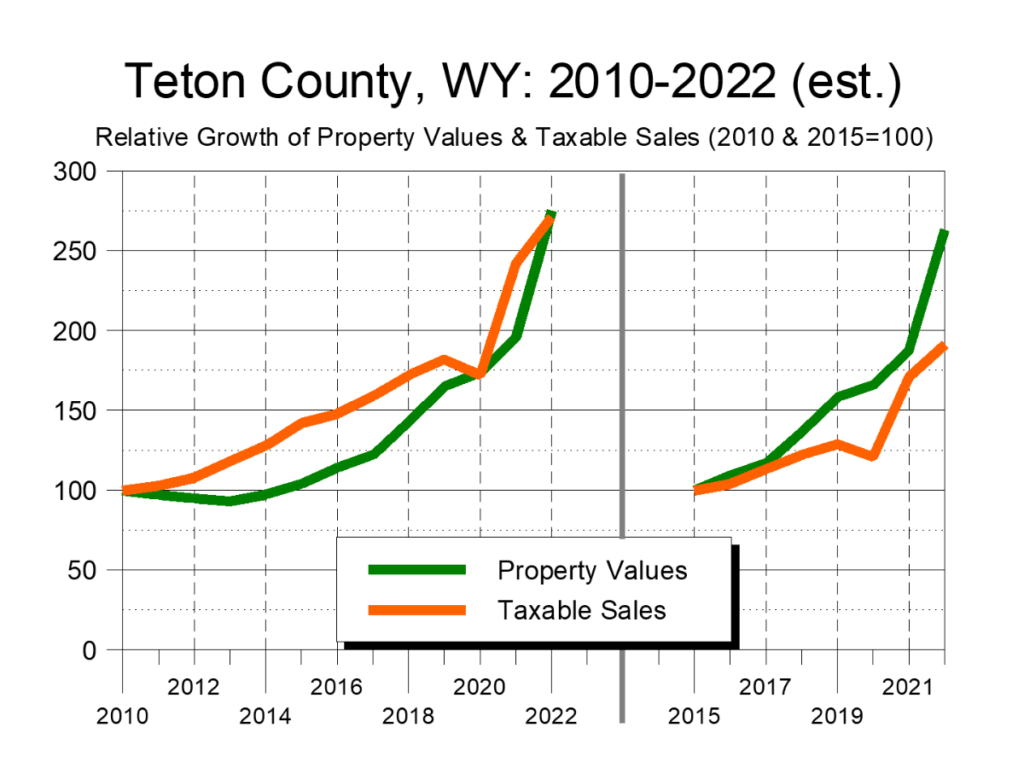

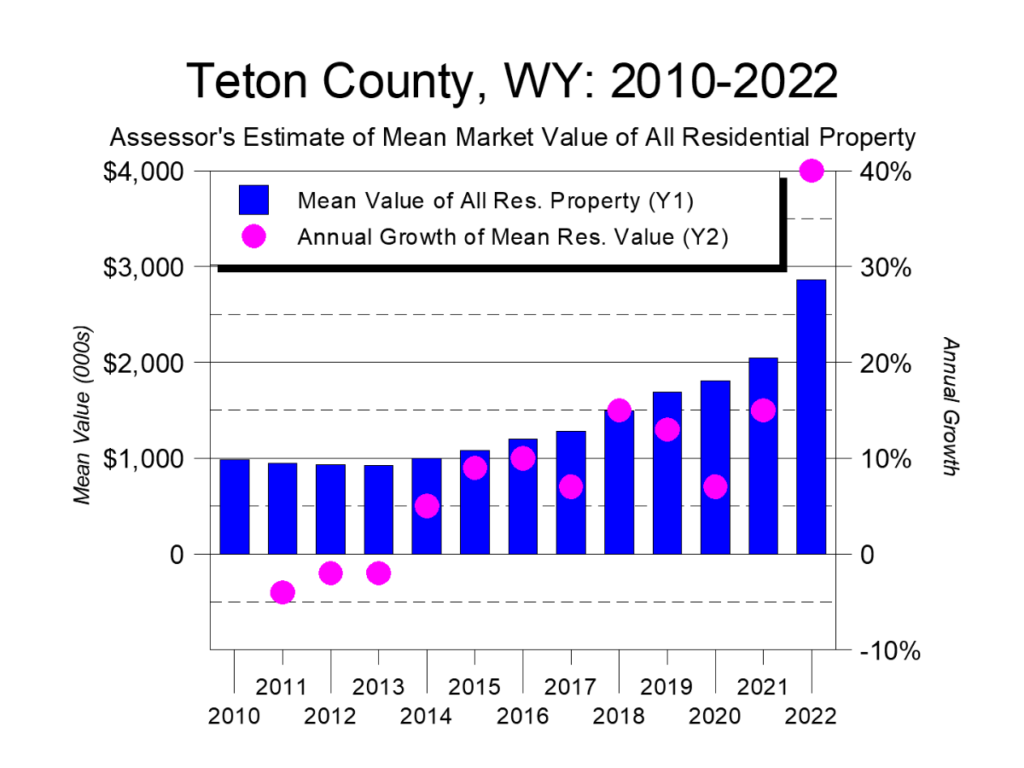

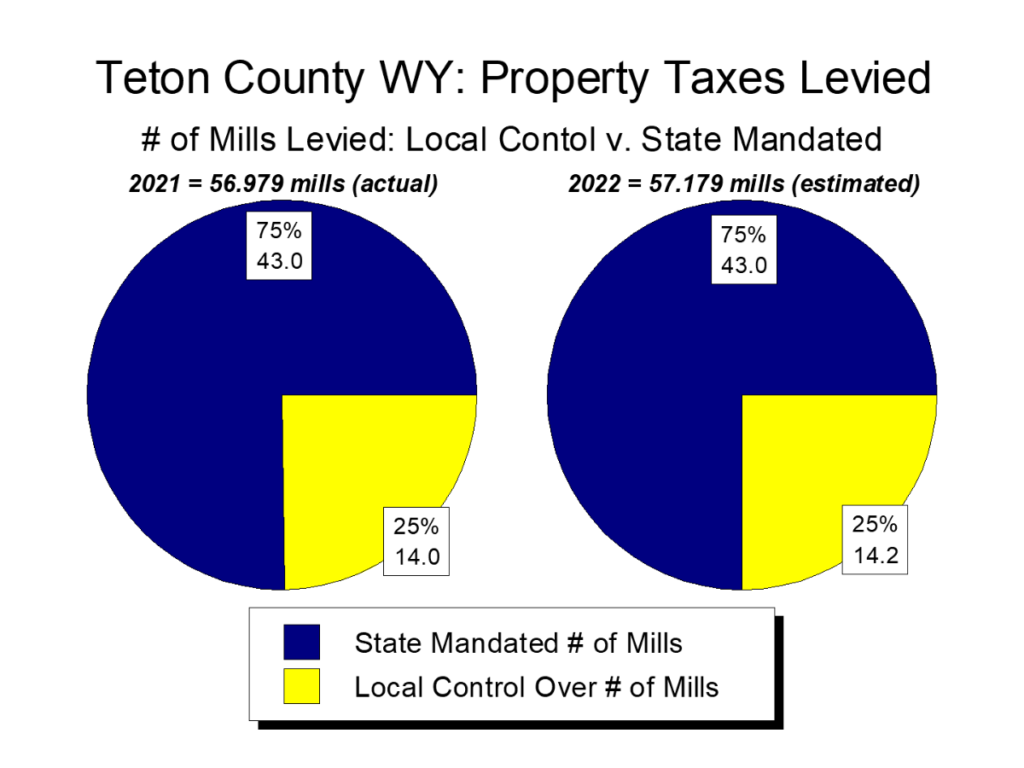

The first was that my last two newsletters focused on Teton County’s rapidly-rising property taxes.

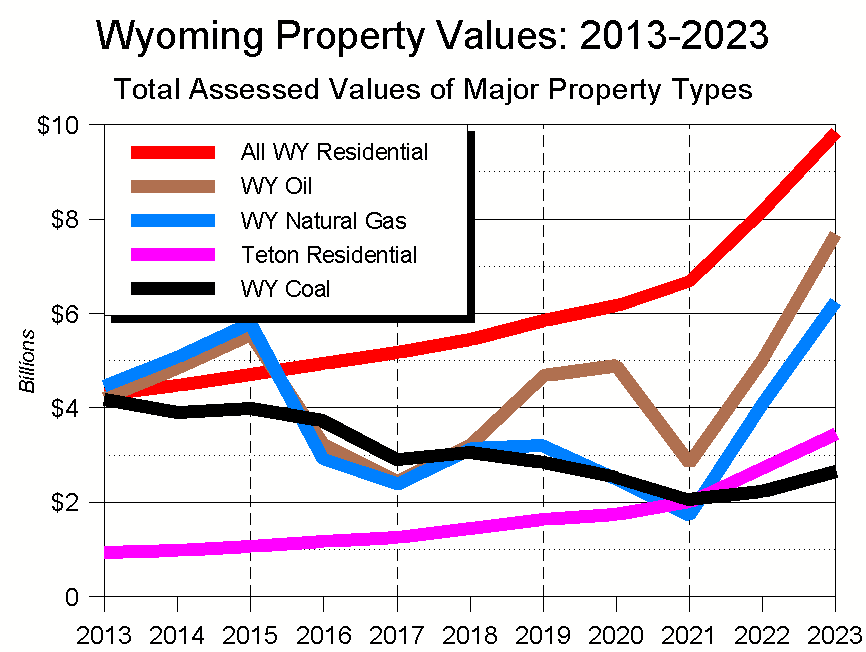

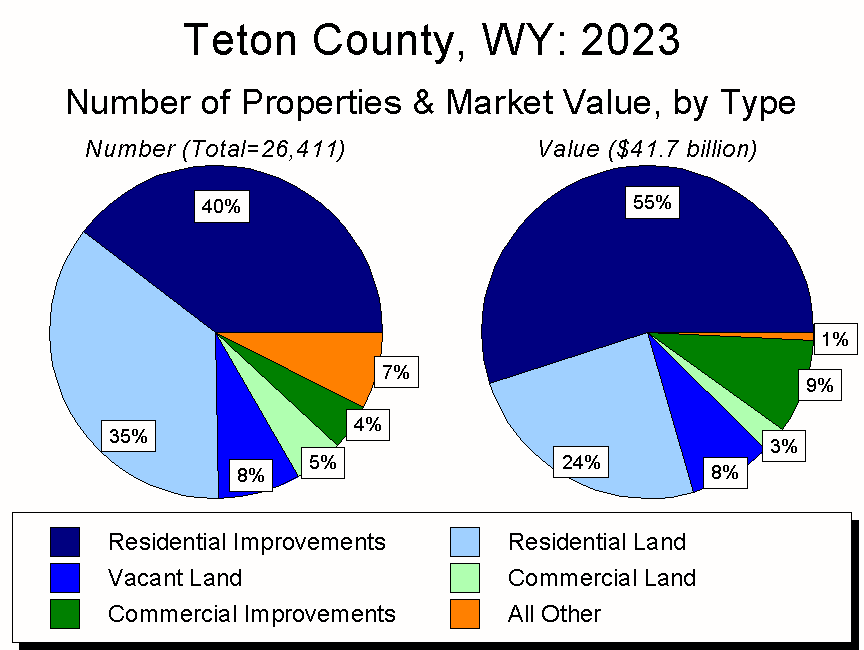

In Wyoming, property taxes reflect property values, which have exploded the past few years. In turn, that got me wondering how much of the boom might have been caused by well-to-do COVID migrants fleeing big cities for the Tetons region.

Pursuing this thought, I dug into a variety of socio-economic data, hoping to find something that would give me a better sense of how – if at all – the forces COVID unleashed might have affected Jackson Hole.

The second occurrence was three business-related events from earlier this month.

First, Apple introduced its new virtual reality headset. While I’ve not tried that device, several years ago I demoed a virtual reality headset that instantly transported me to the center of a large alpine lake. Floating contentedly, I was surrounded by mountains, the distant shoreline, a variety of birds, and other familiar sights. Then, out of nowhere, I was hit by a locomotive. No tracks, no warning. Just a steam engine running at full speed on top of the water. The experience was so vivid, so visceral, and so completely beyond comprehension that it seared itself into my memory.

Second, the world’s largest cruise ship had its maiden voyage. The Icon of the Seas holds 7,500 passengers and 2,500 crew, meaning its population is about the same as Jackson’s. The ship boasts the largest waterpark at sea, the world’s largest floating ice rink, a surf simulator, a casino, nightclubs, stage shows, gardens and a park, and a variety of other features. In other words, a whole bunch of attractions you could find on land – think Las Vegas – except they’re on a boat.

Third was Las Vegas itself, which hosted the Super Bowl. Sort of like the Icon of the Seas, Las Vegas amalgamates, commodifies, and Vegas-izes a hodgepodge of features from other places – Paris, New York, ancient Rome, where have you – and puts them into a setting basically disconnected from the natural world around it. In other words, Las Vegas creates its own type of virtual reality.

My thoughts about Apple, the Icon, and Las Vegas shaped my COVID-related analysis. To telegraph my punches, here’s what I found.

Between 2018-2022 – i.e., during the years straddling the heart of the COVID pandemic – eight of the ten counties in America that experienced the biggest surge in wealth – America’s leading “Wealth Attractor” counties – shared a common quality: They are distinguished not by virtual reality, but by the by-God actual reality that only the natural world can offer. The eight were:

- Eagle, Pitkin, Routt, and San Miguel counties in Colorado (the homes of Vail, Aspen, Steamboat, and Telluride respectively)

- Blaine County, Idaho (Sun Valley)

- Douglas County, Nevada (South Lake Tahoe)

- Summit County, Utah (Park City) and

- Teton County WY (Jackson Hole).

The only exceptions to the “money moved to places closely linked to the natural world” rule were Denver County, Colorado (Denver) and San Mateo County, California (Silicon Valley).

We can quibble about how “real” places like Aspen and Vail are, but the simple reality is that, during COVID, the places which attracted people who could live anywhere were those closely tied to the natural world. Not a virtual headset or trees-at-sea version of the natural world, but the real deal.

I think that’s profoundly important in what it says about our values. It’s arguably even more important in what it suggests about pressures Jackson Hole and similar communities will be facing going forward.

As always, thank you for your interest and support.

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

PS – Based on the feedback I received from my last newsletter, readers like puppy photos at least as much as socio-economic analysis. Pandering to that audience, please find below more cuteness and fierceness.

Introduction

Four years ago, COVID-19 upended seemingly every aspect of American life.

After a couple of years of upheaval, things have arguably settled into a “new normal,” a world in which many previous assumptions about work and home no longer seem to apply.

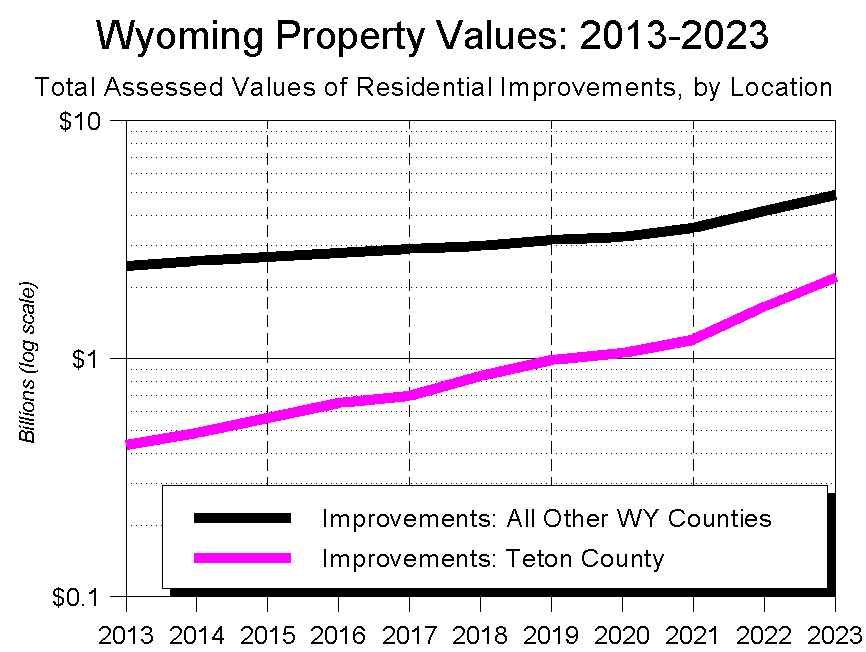

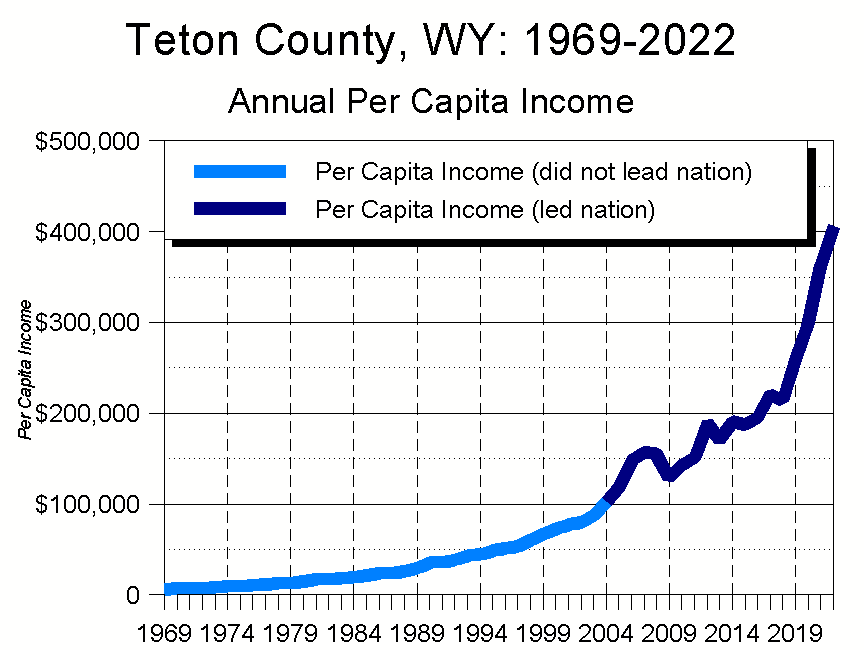

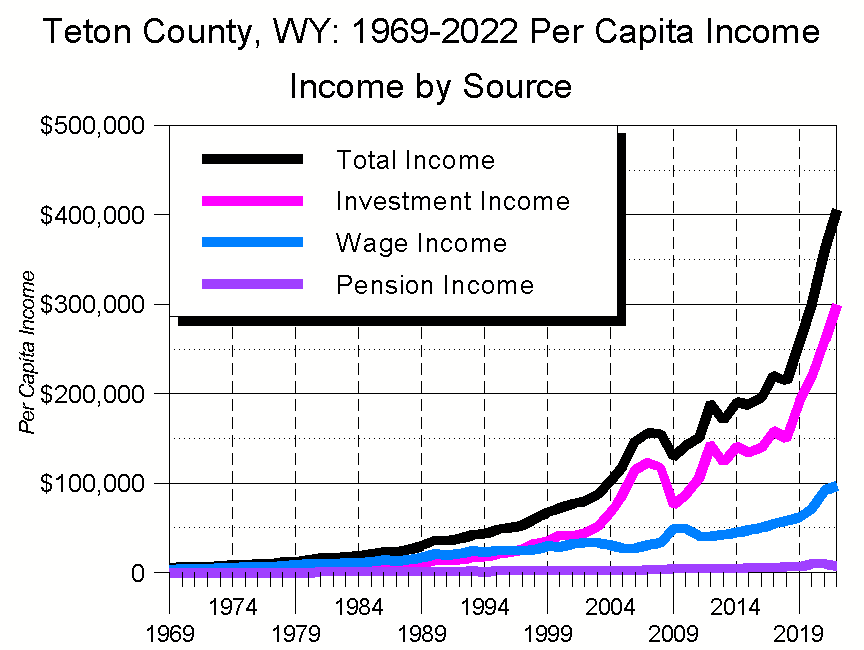

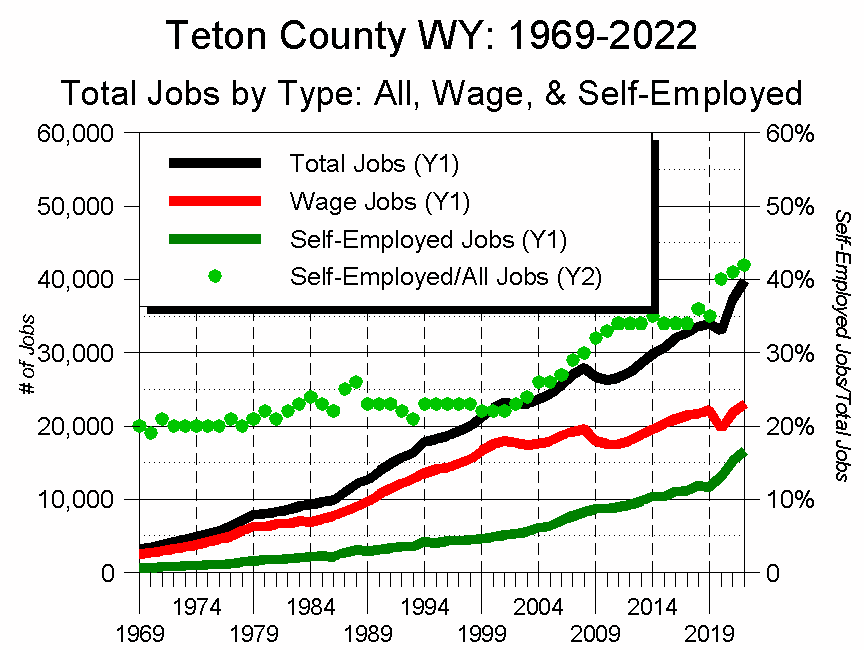

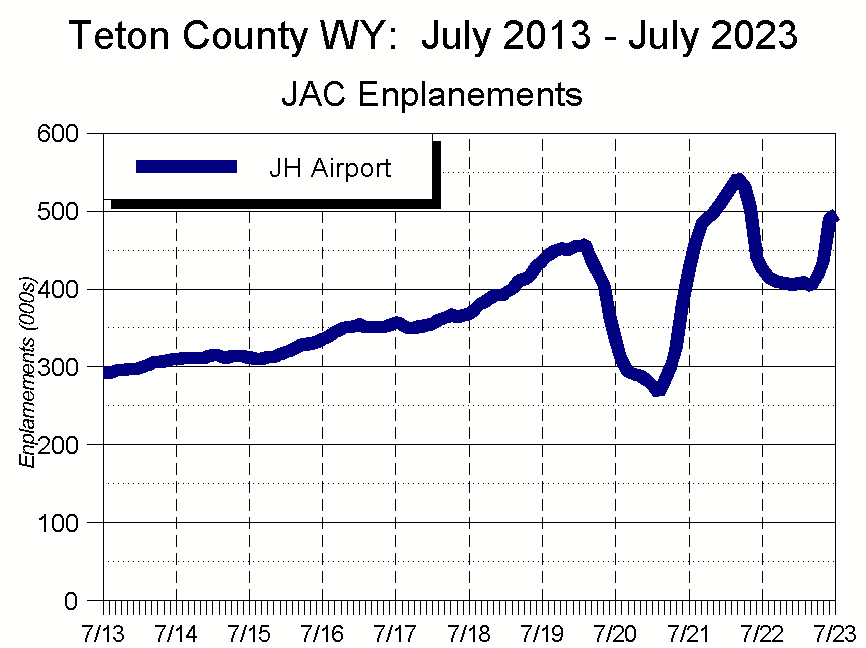

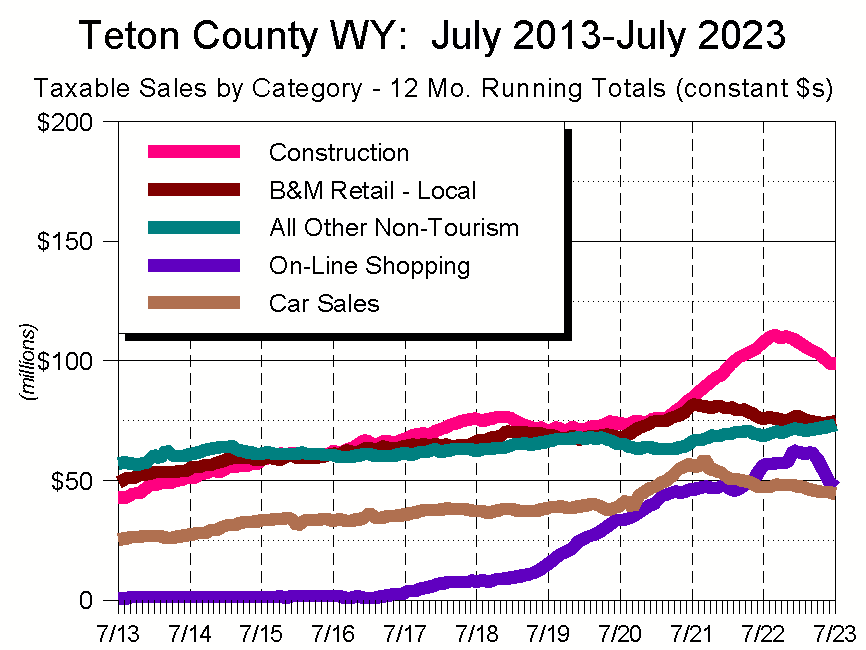

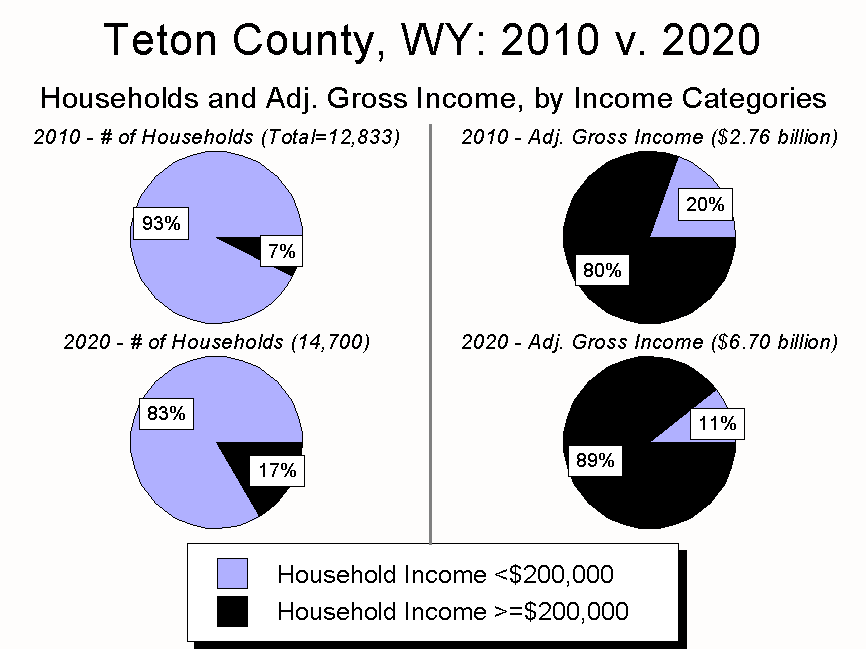

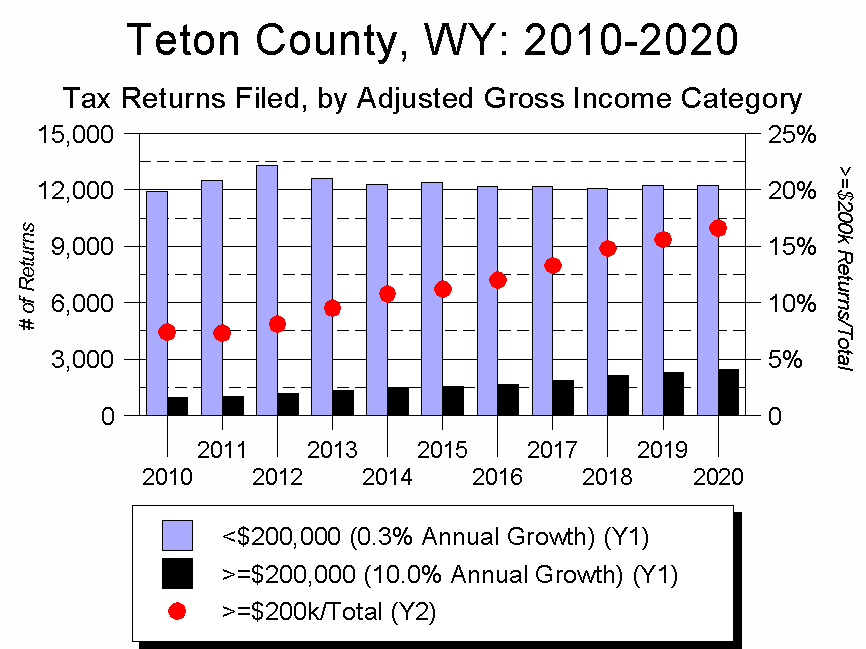

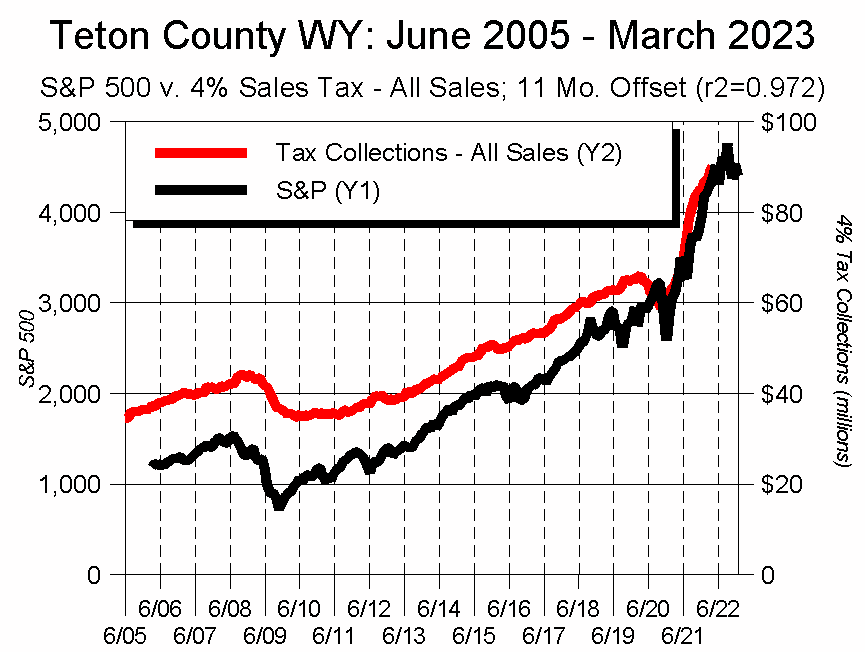

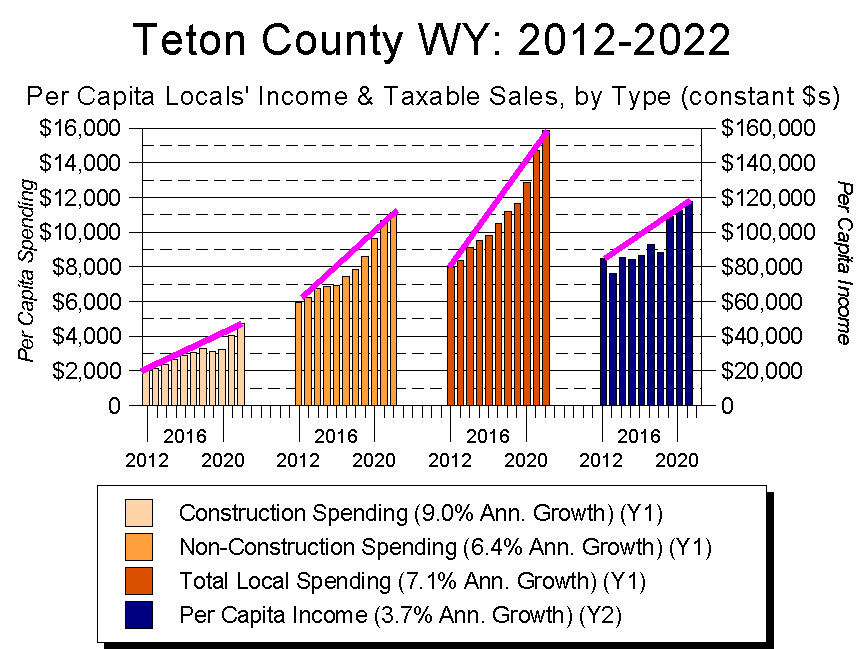

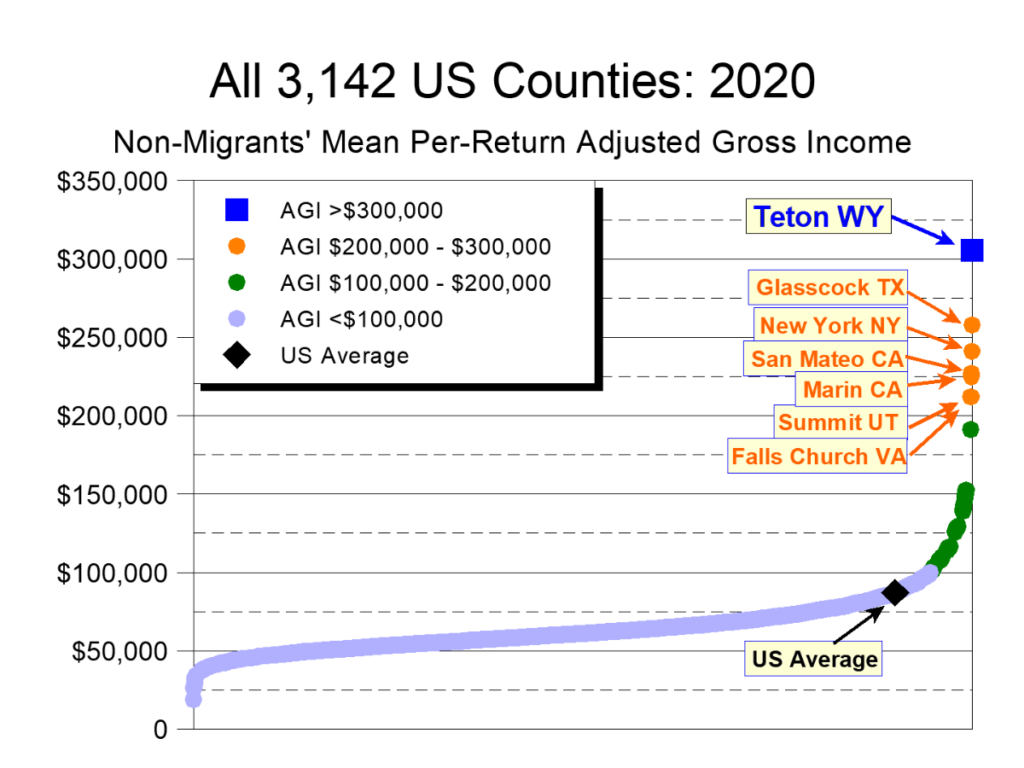

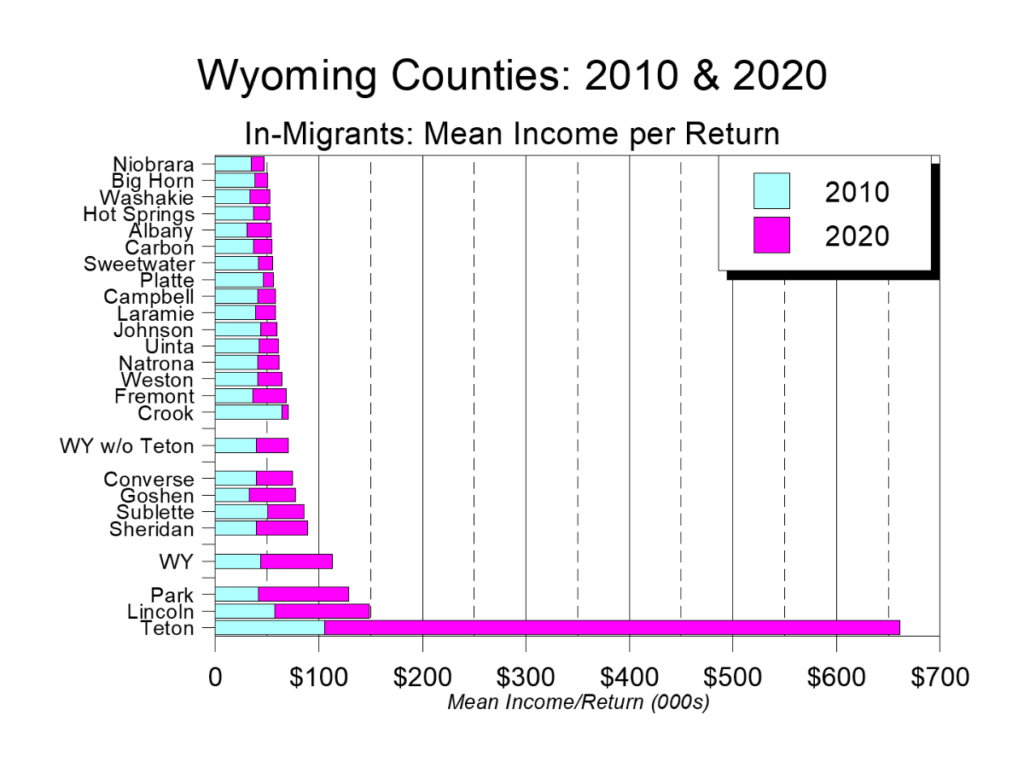

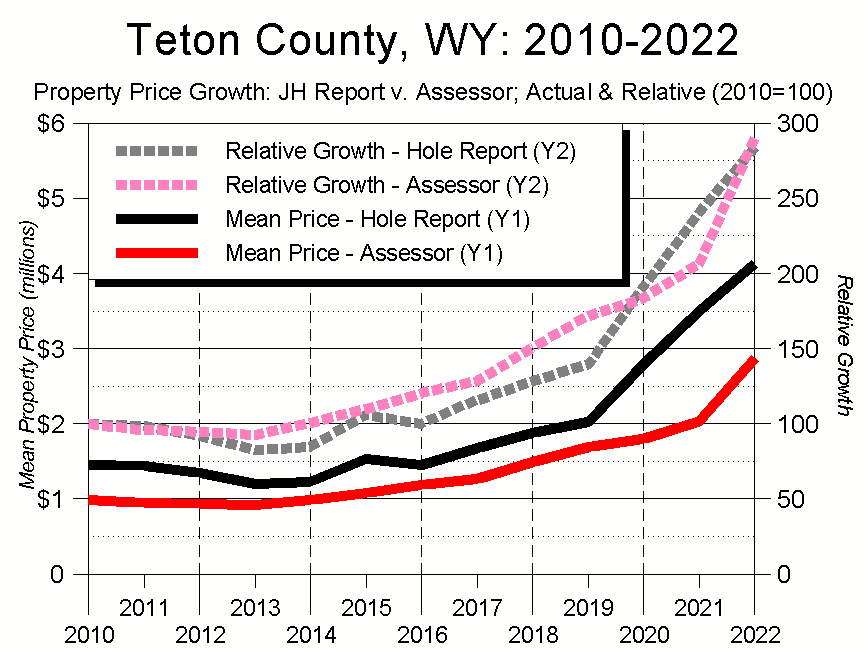

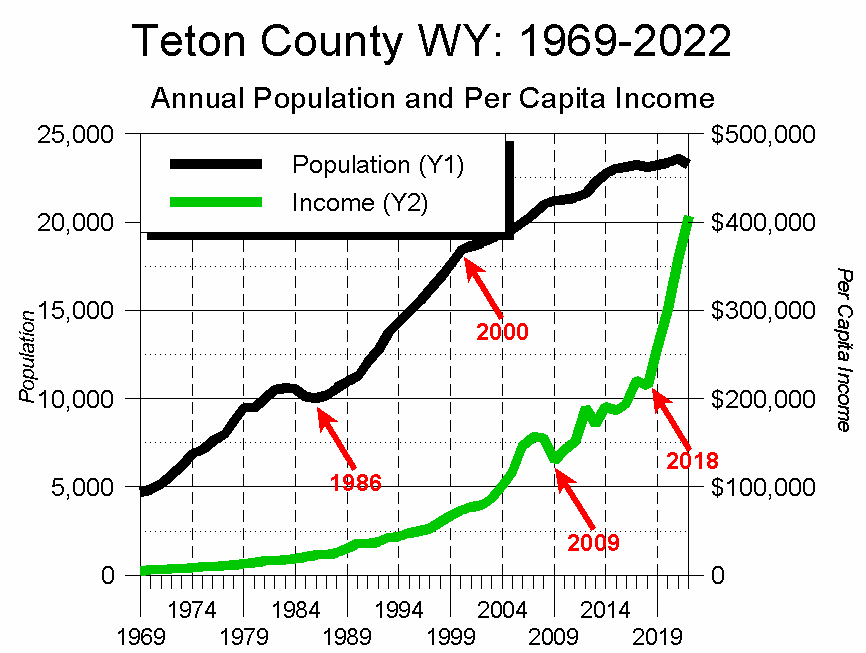

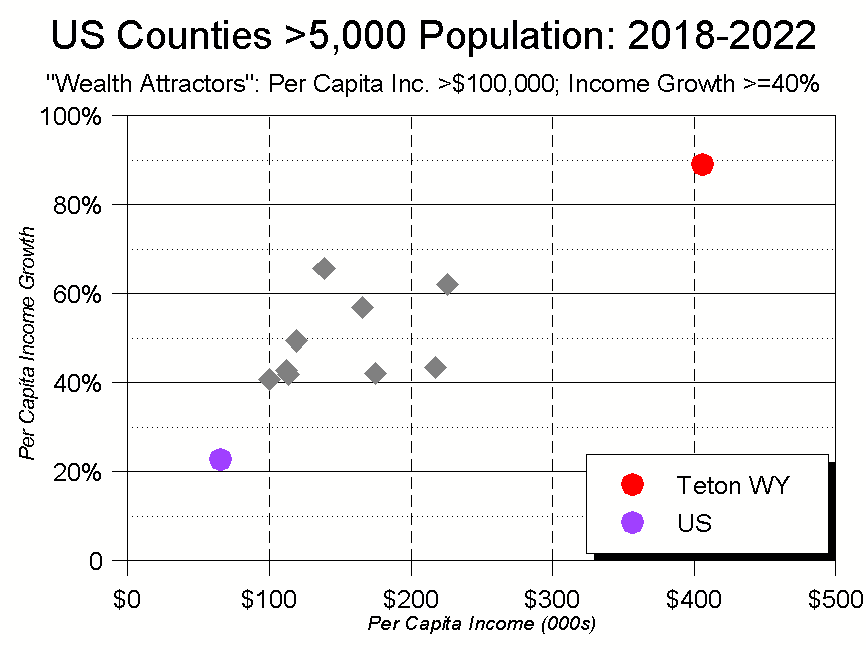

To better understand how we got here, I looked at some basic population, income, and jobs data about every county in the US. I focused on the years 2018 and 2022: the former because that was the last year before Teton County, WY’s recent, extraordinary growth in income; the latter because that is the most recent year’s data available. (Figure 1)

Findings

In 2022, there were 3,088 counties or, as the geographers say, “county equivalents” in the United States. Of these, 2,769 – roughly 90% – had more than 5,000 residents. In the analysis below I focused on these larger counties because smaller counties’ sizes make them susceptible to huge, often nonsensical variations in growth rates.

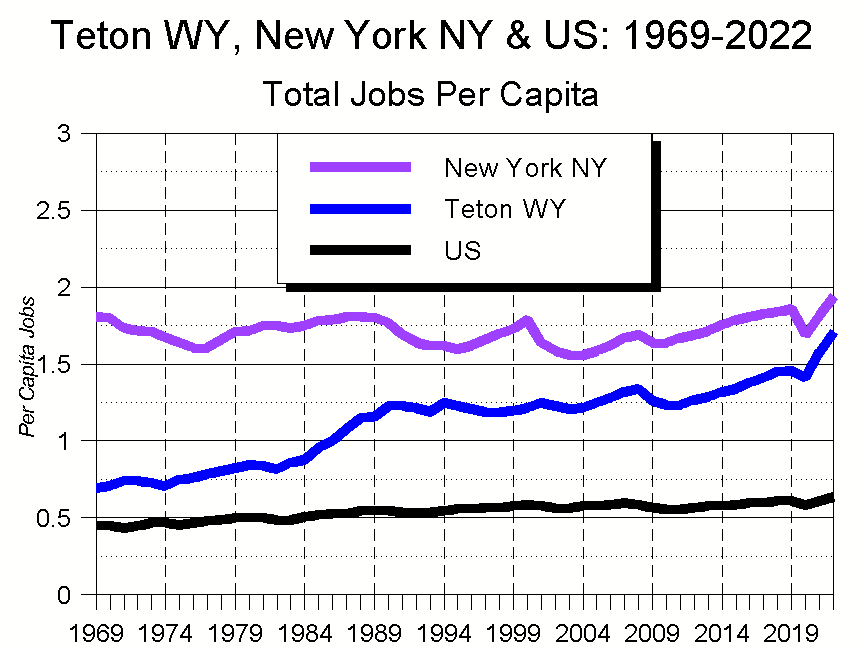

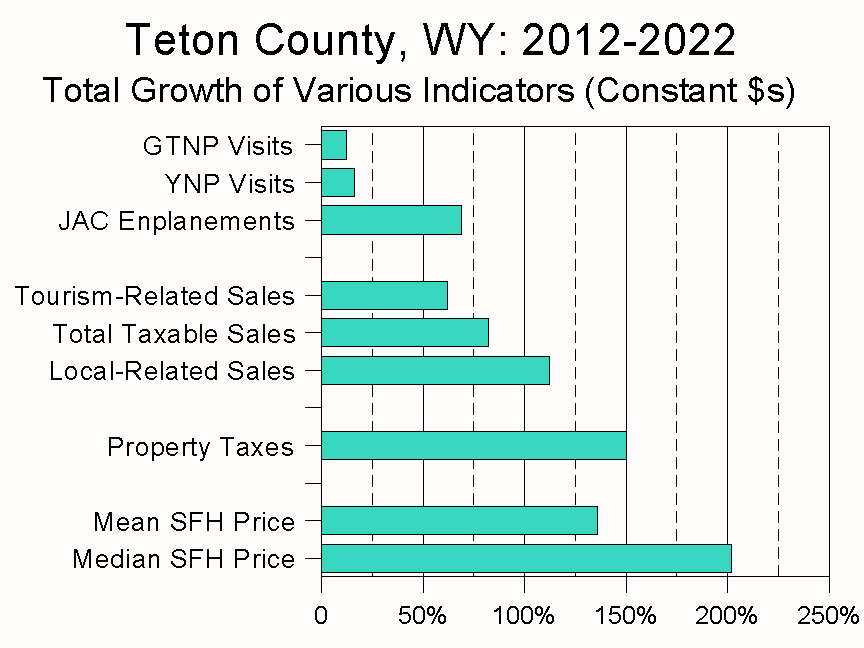

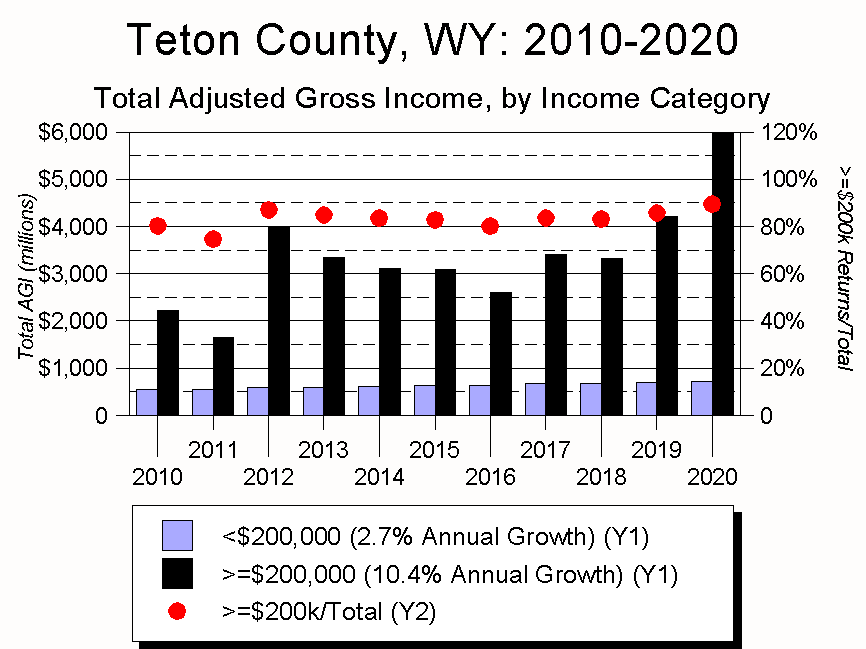

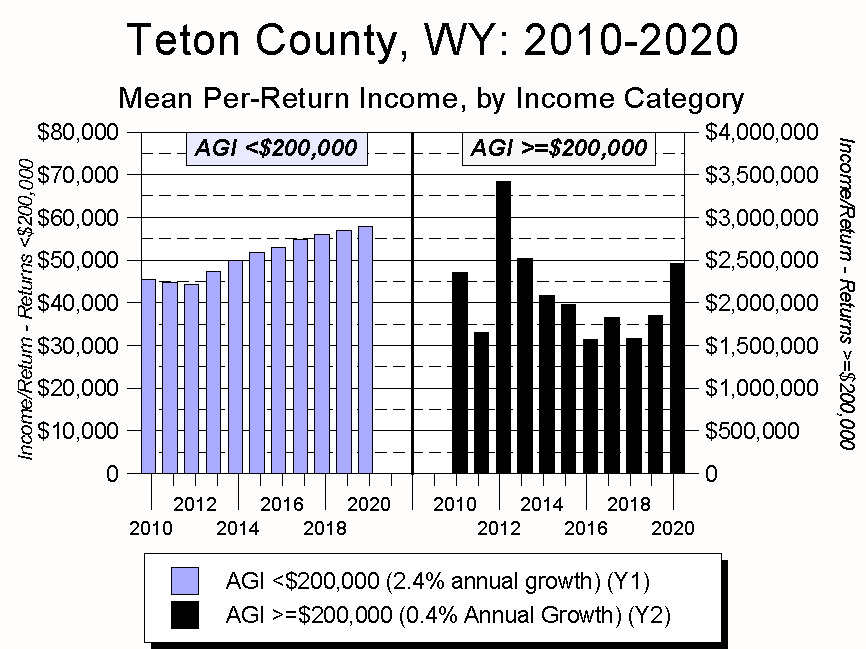

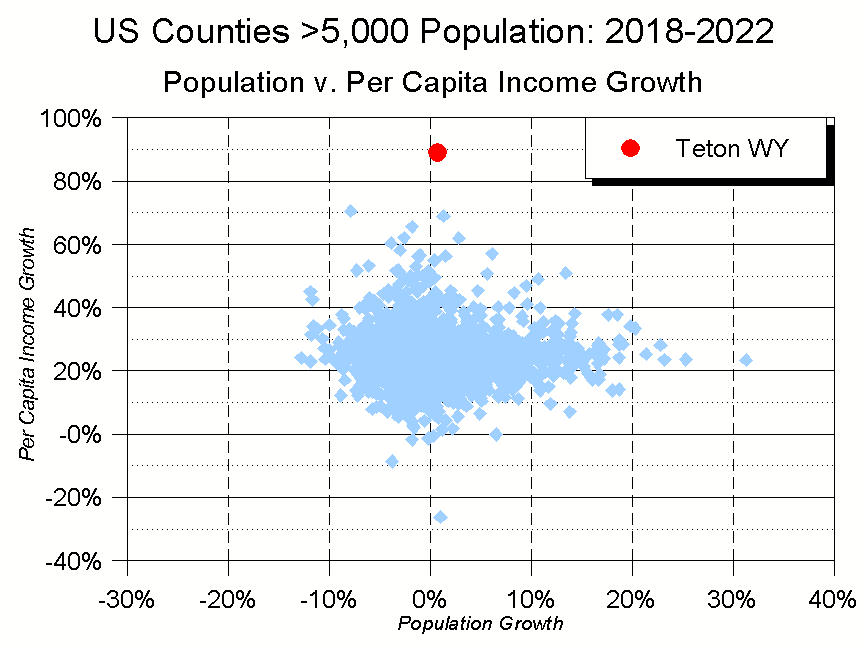

If you pose the question “Between 2018-2022, did counties’ per capita income growth correlate well with their population growth?” the answer is “Nope.” What does emerge from asking this question, though, is that during that particular four-year span, Teton County, Wyoming enjoyed the nation’s greatest per capita income growth: 89%. (Figure 2)

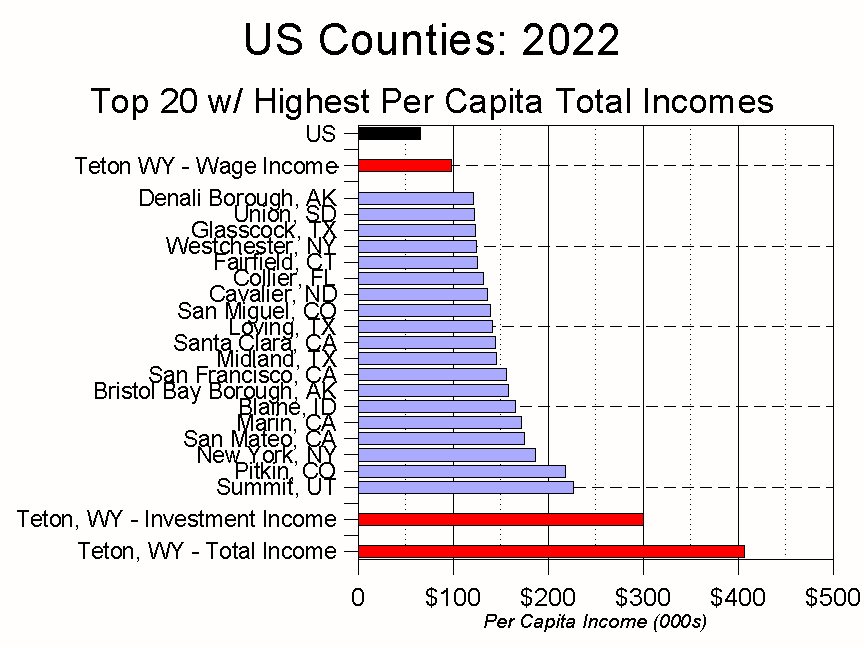

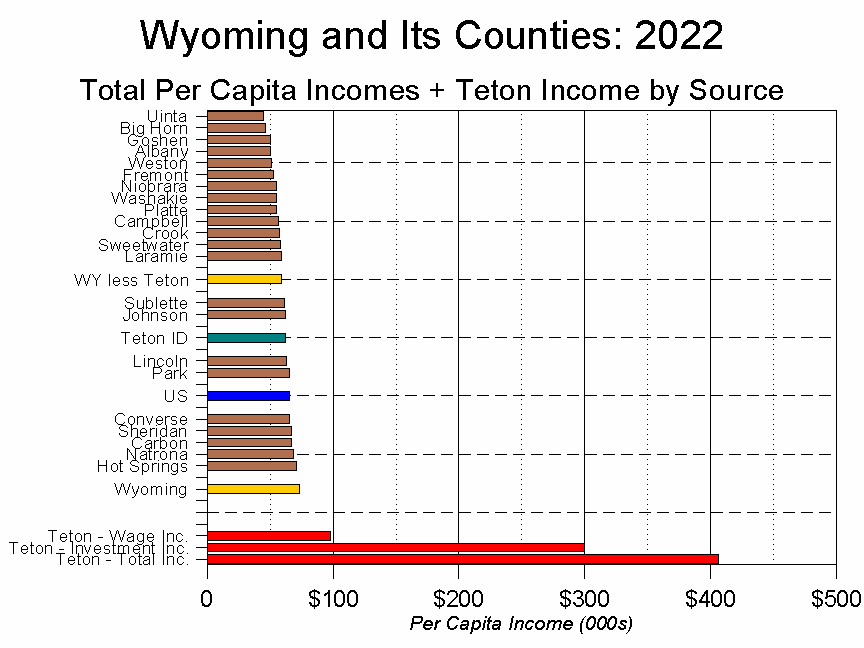

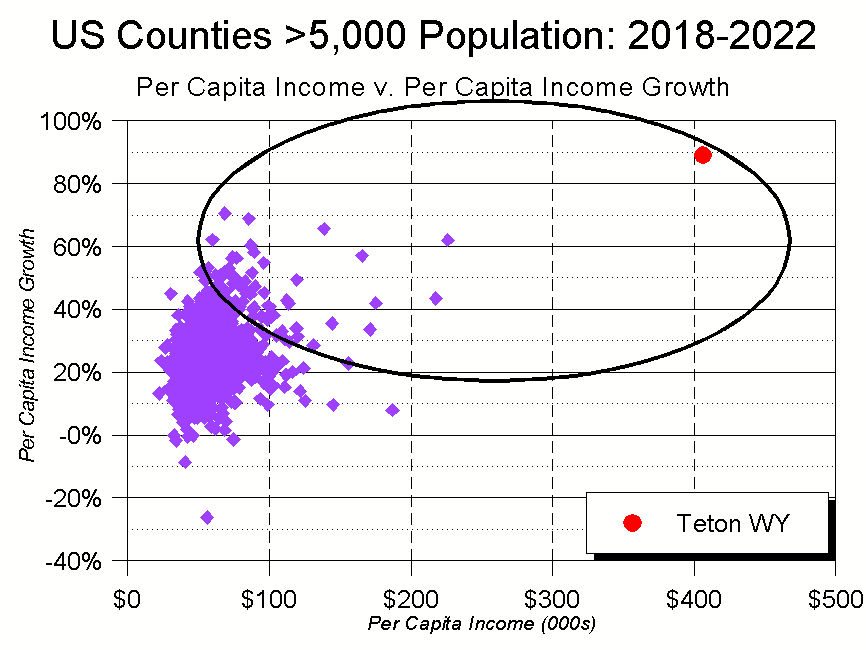

Since per capita income growth v. population growth got me nowhere, I decided to replace population growth with 2022 per capita income. While that proved mostly inconclusive, it did highlight two facts.

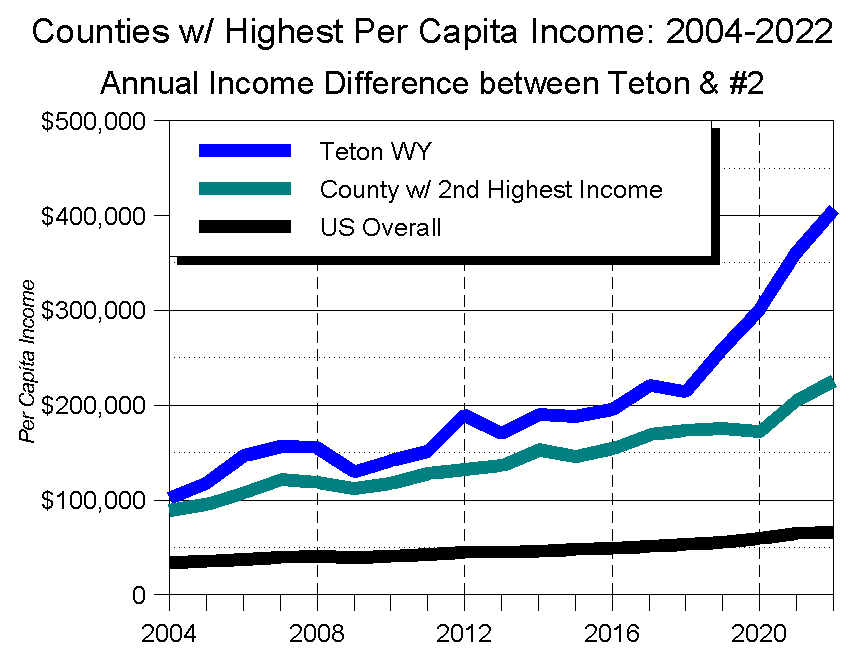

One was that, in 2022, Teton County led the nation in both 2018-2022 per capita income growth and 2022 per capita income (Teton County has had the nation’s highest per capita income every year since 2004). No county had led in both income and four-year growth rate since New York, NY in 1998.

The second fact was that, in contrast to Figure 2’s population-growth-versus-income-growth blob, there seemed to be a bit more going on when I compared annual income to four-year income growth. This phenomenon is captured by the oval surrounding the higher-income, higher-growth counties in Figure 3.

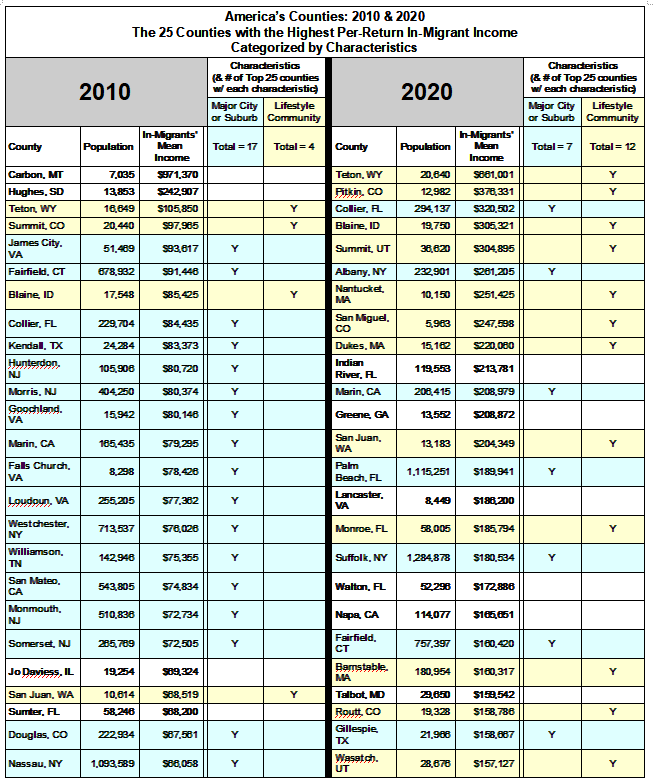

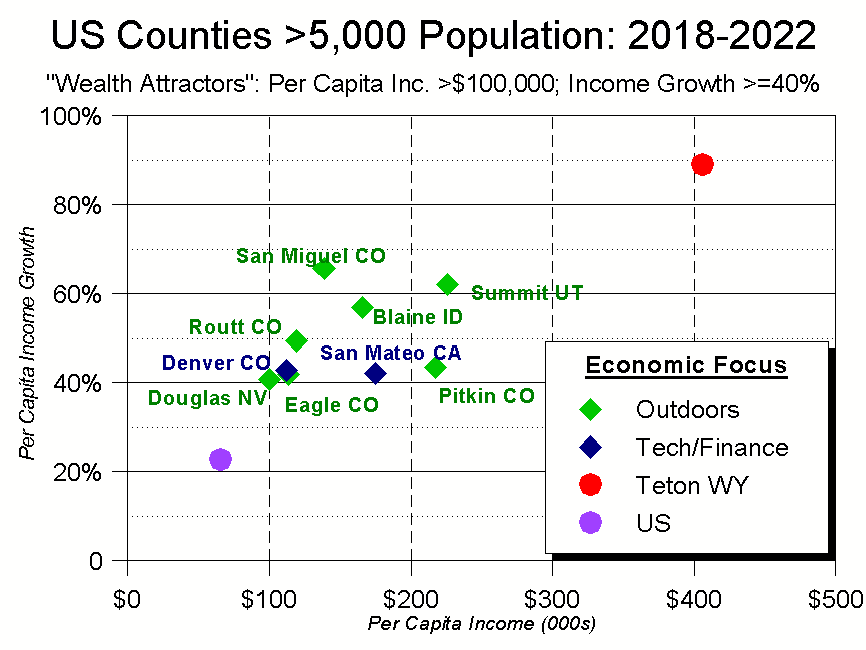

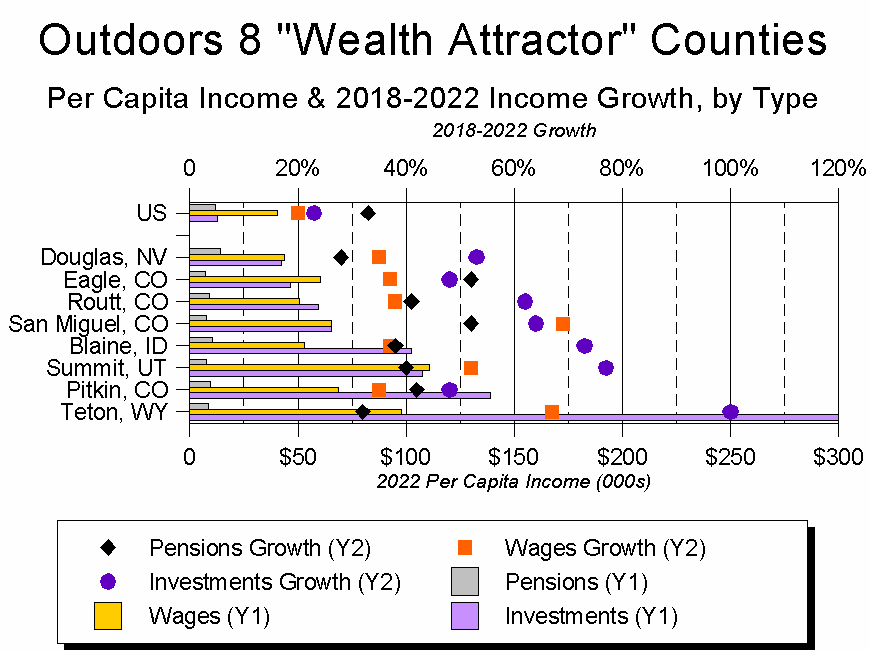

Building on this, I created Figure 4 by running Figure 3’s data through two filters: counties with per capita incomes of $100,000 or more, and counties with at least 40% growth in per capita income between 2018-2022. Ten counties met both criteria, suggesting that these were the places where, during COVID, people who could afford to live anywhere were choosing to live. My term for these counties is the “Wealth Attractors.” (Figure 4)

Figure 5 is the same as Figure 4, but with the ten counties identified and categorized. Doing this, what leaps off the page is that eight of the ten counties were ones whose characters and economies are directly linked to the natural world around them. In fact, the six with the biggest growth in per capita income were all “outdoors” counties, along with #s 8 and 10. Combined, I refer to these counties as the “Outdoors 8.” (Figure 5

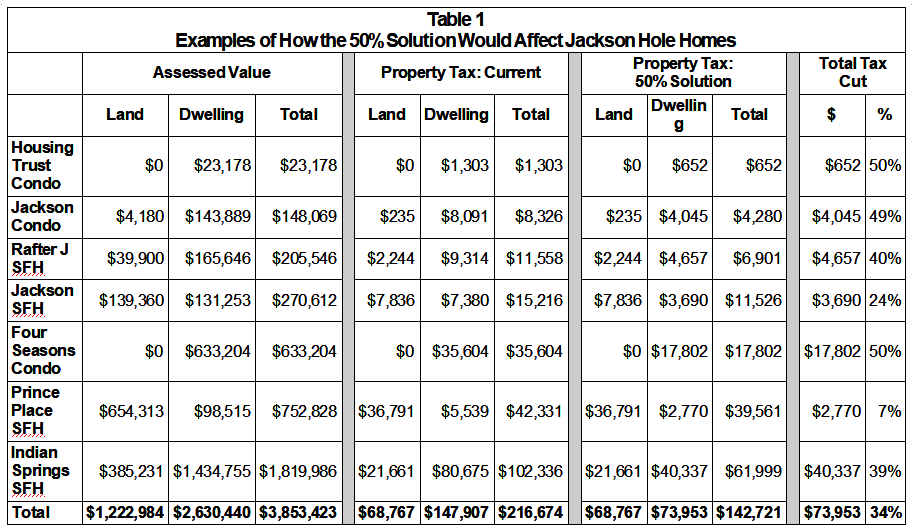

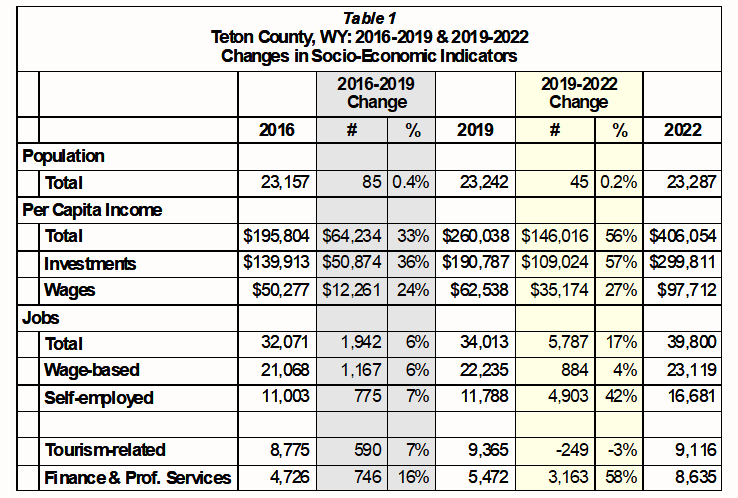

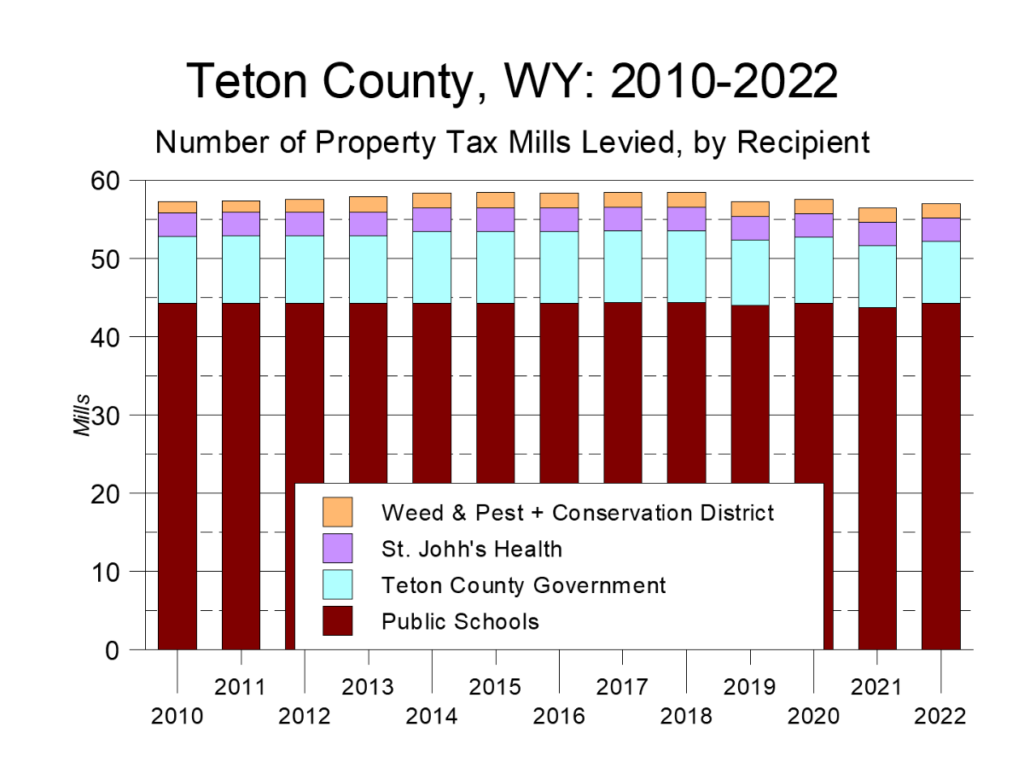

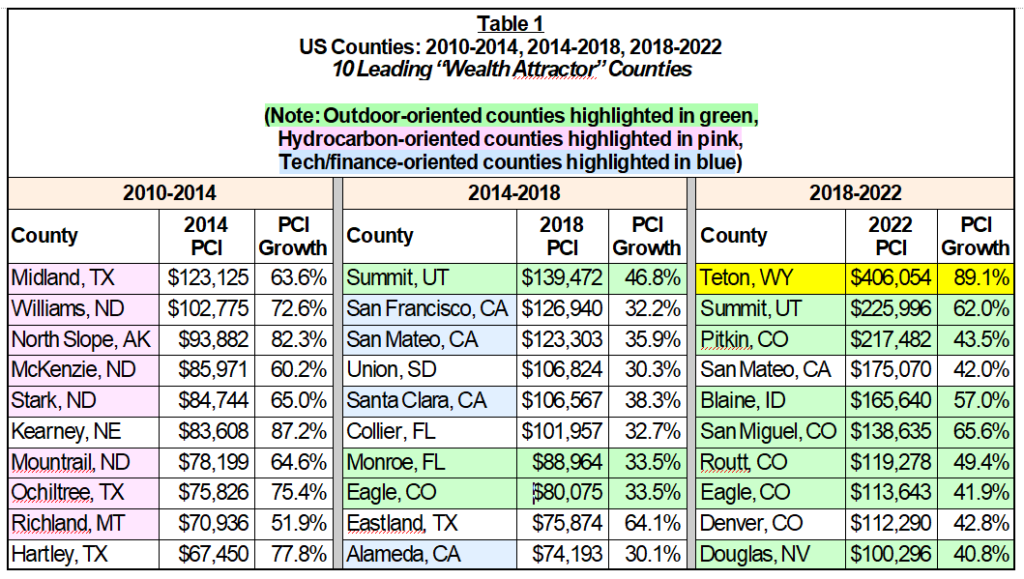

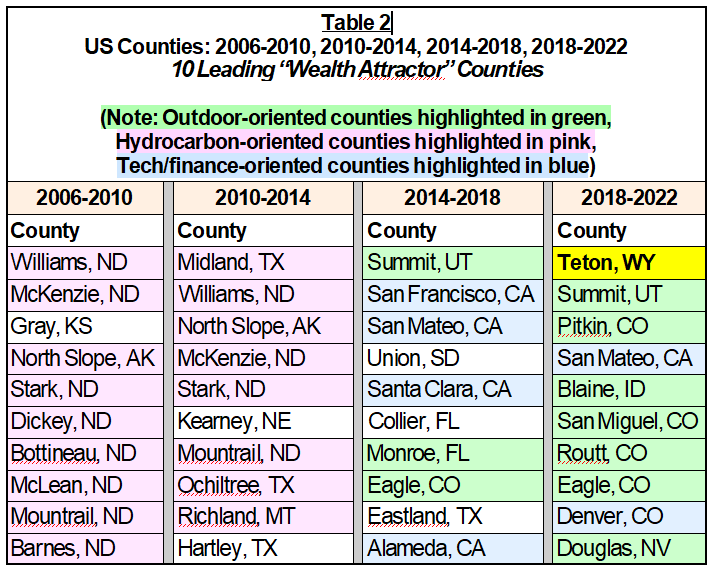

This emphasis on locale had never occurred before. For example, between 2010-2014 the places with the greatest increase in wealth were, broadly speaking, places associated with hydrocarbons and the fracking boom; between 2014-2018, it was more about tech. Between 2018-2022, though, people with means sought out places closely tied to the natural world. (Table 1)

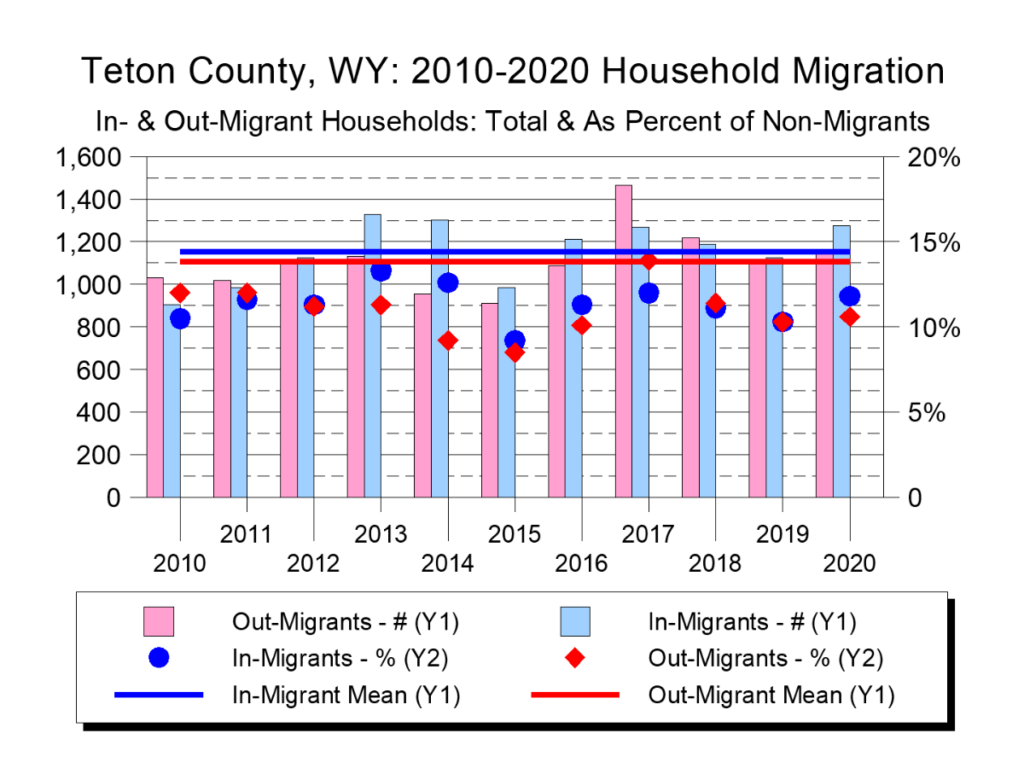

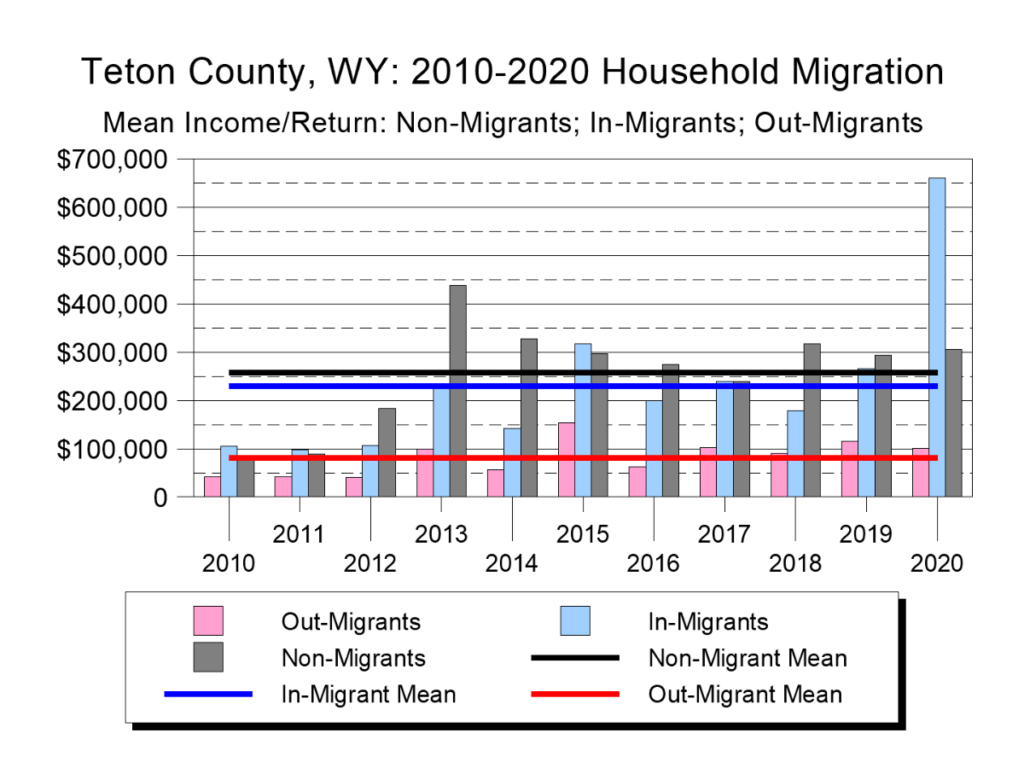

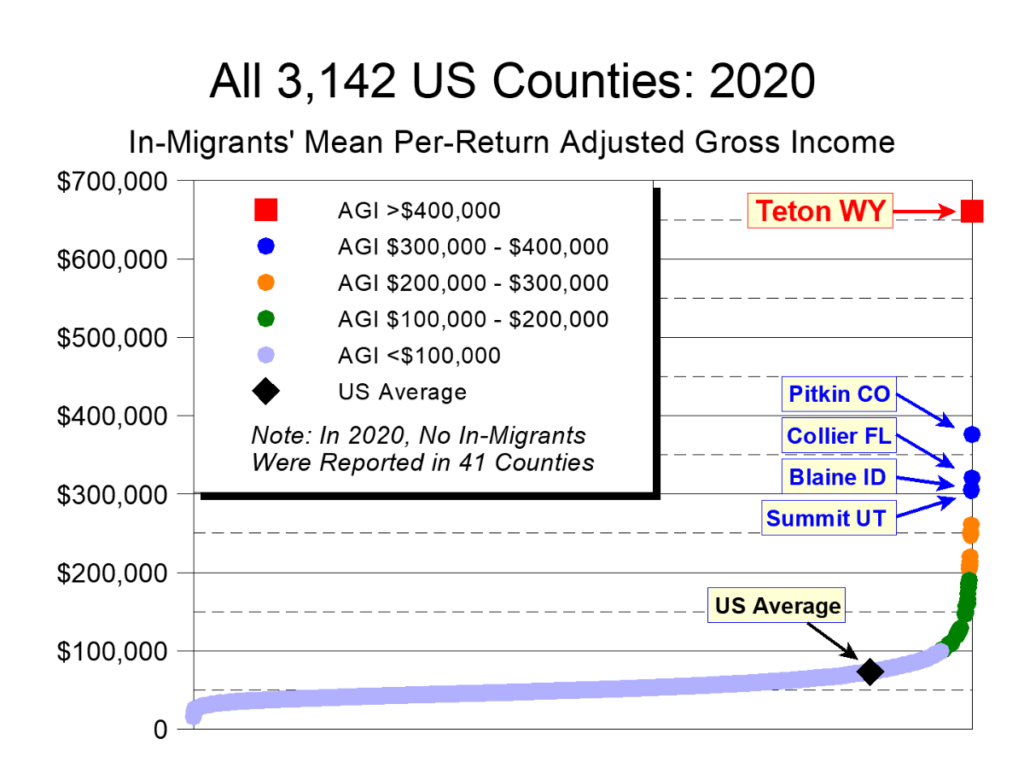

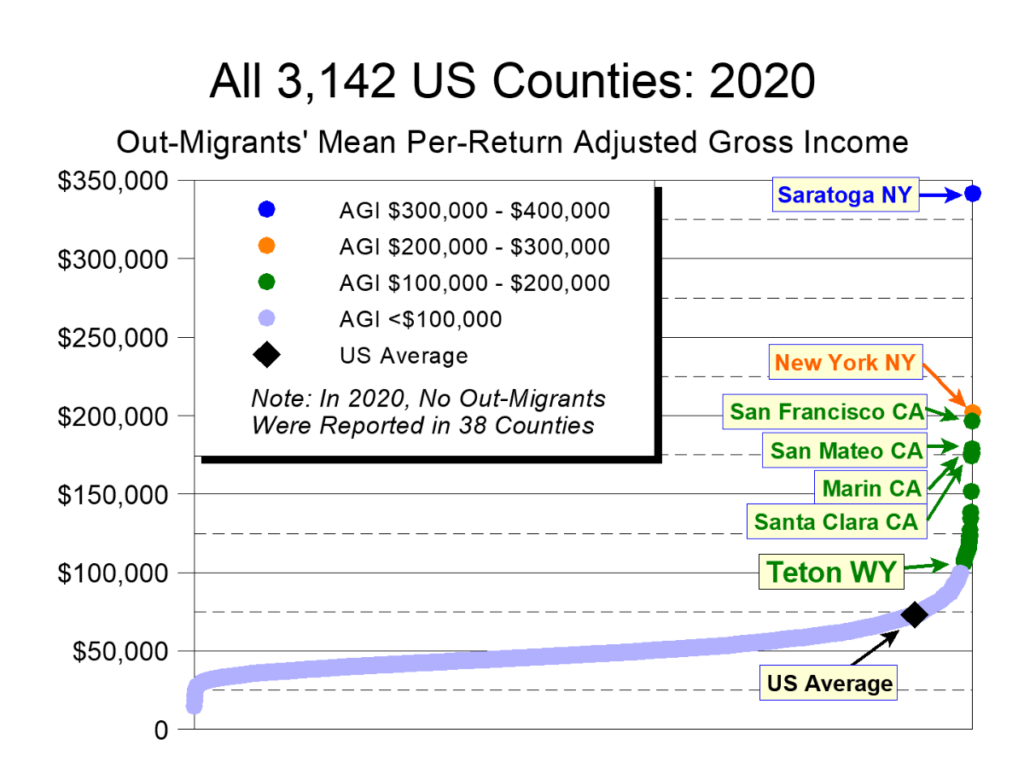

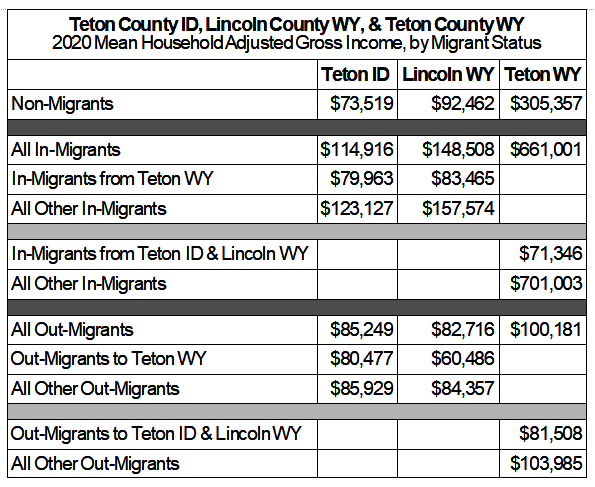

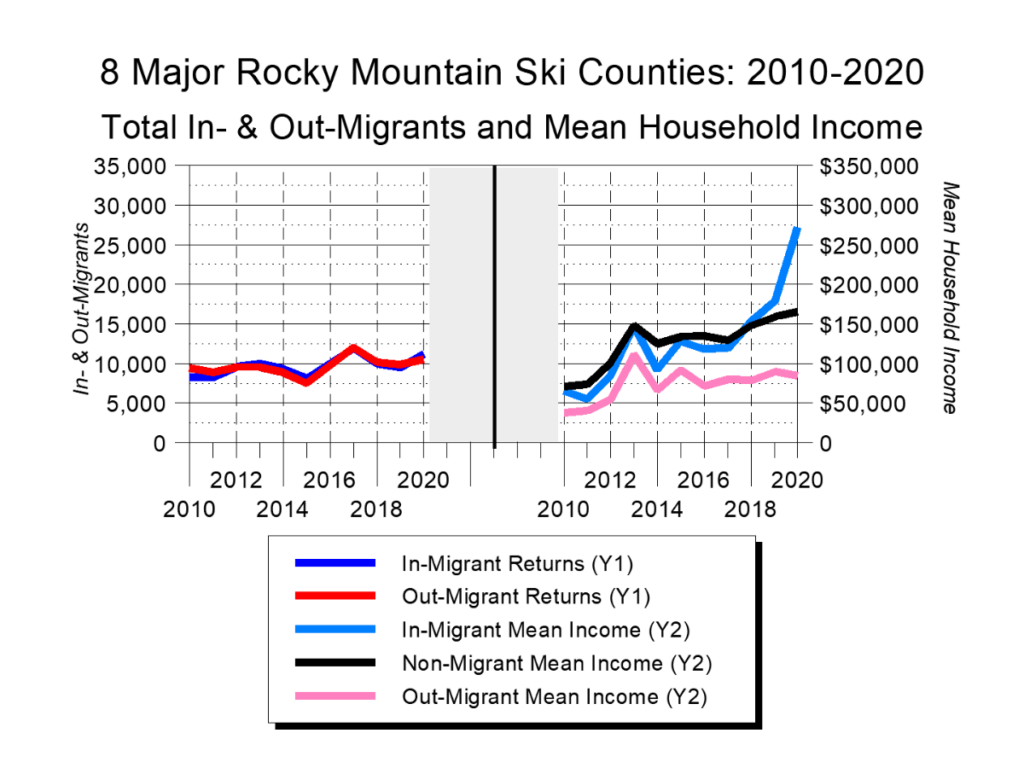

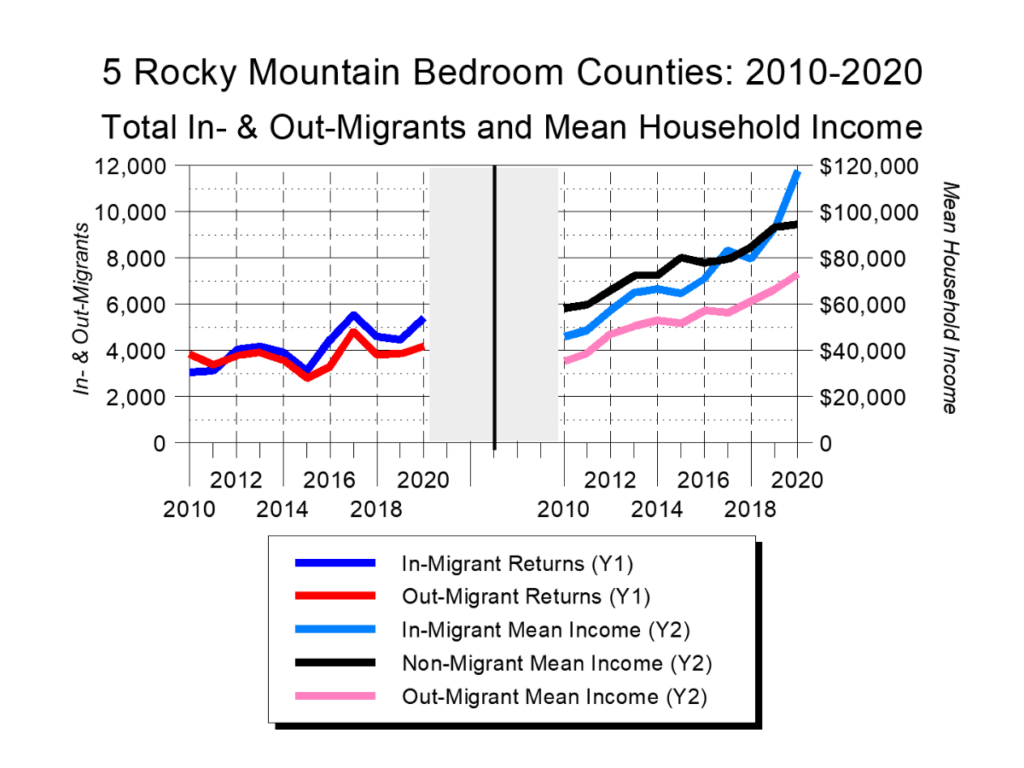

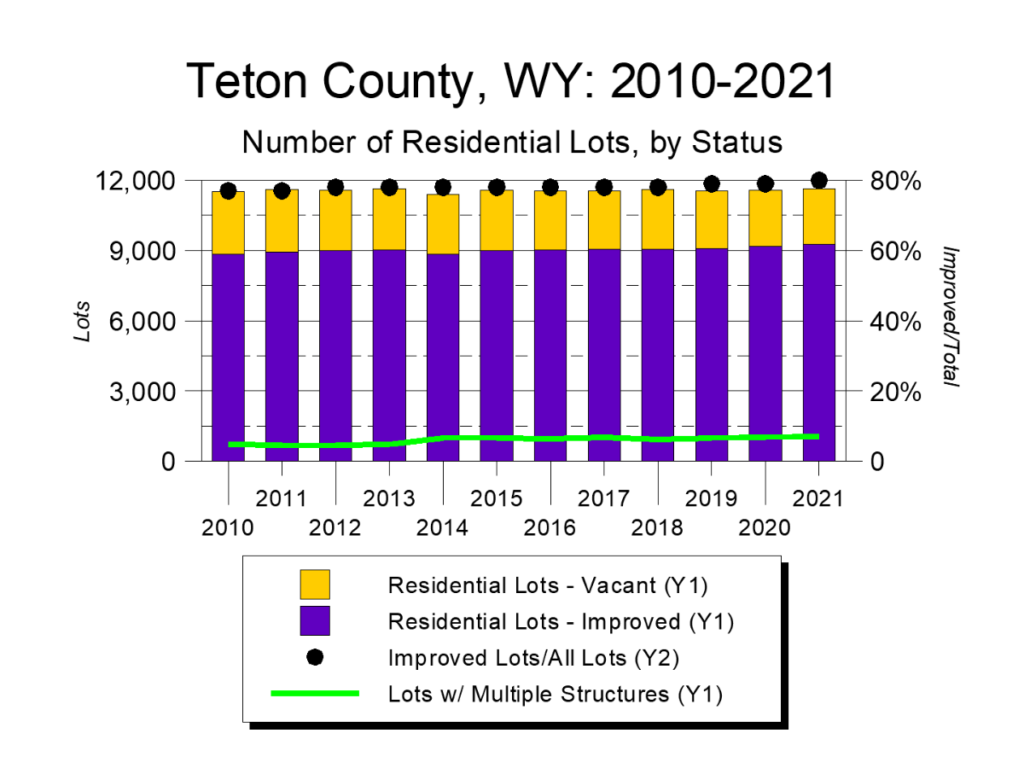

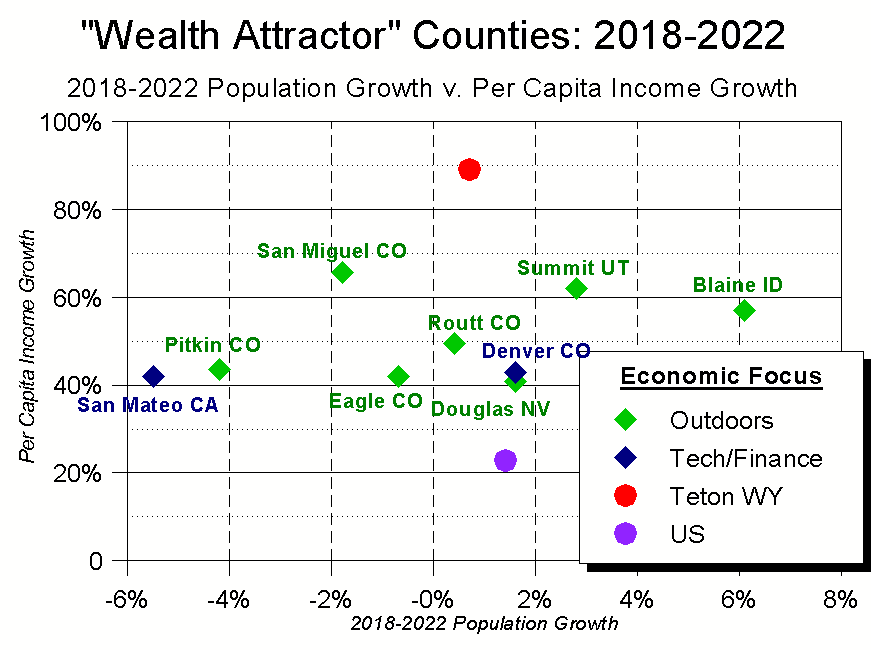

So what happened? Well, one thing that didn’t happen was a big population surge in the Outdoors 8. In fact, three of the Outdoors 8 lost population between 2018-2022, and only one saw its population grow more than 3% (during that period, the nation’s population grew 1.4%). This suggests that the Outdoors 8’s surge in incomes came not because of population growth, but because of population turnover; i.e., less well-to-do residents were displaced by new, well-to-do ones. (Figure 6)

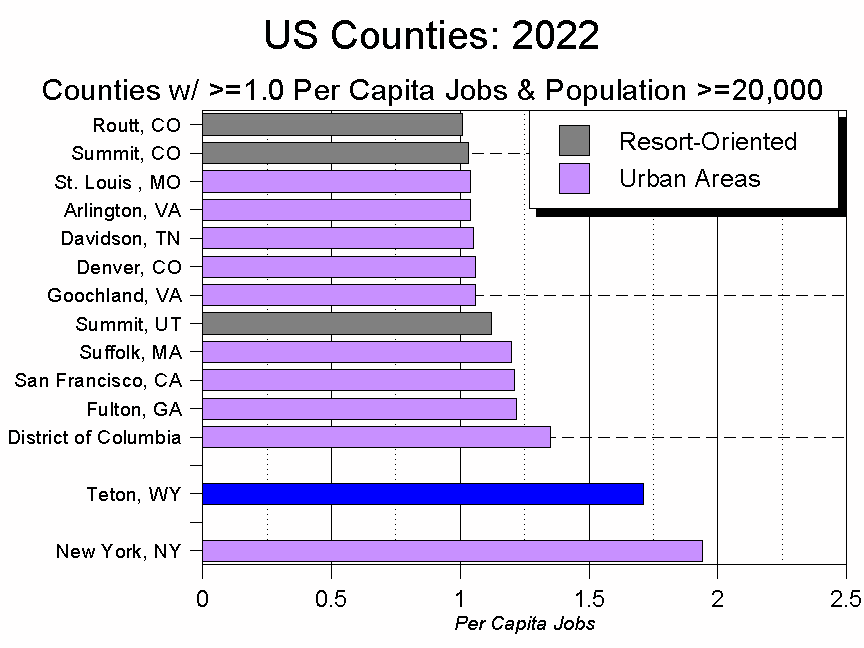

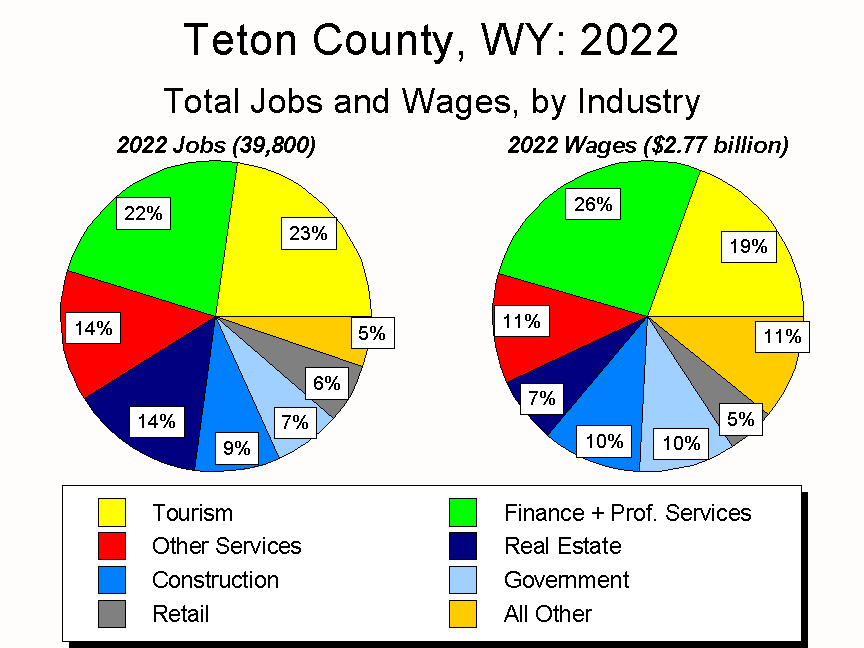

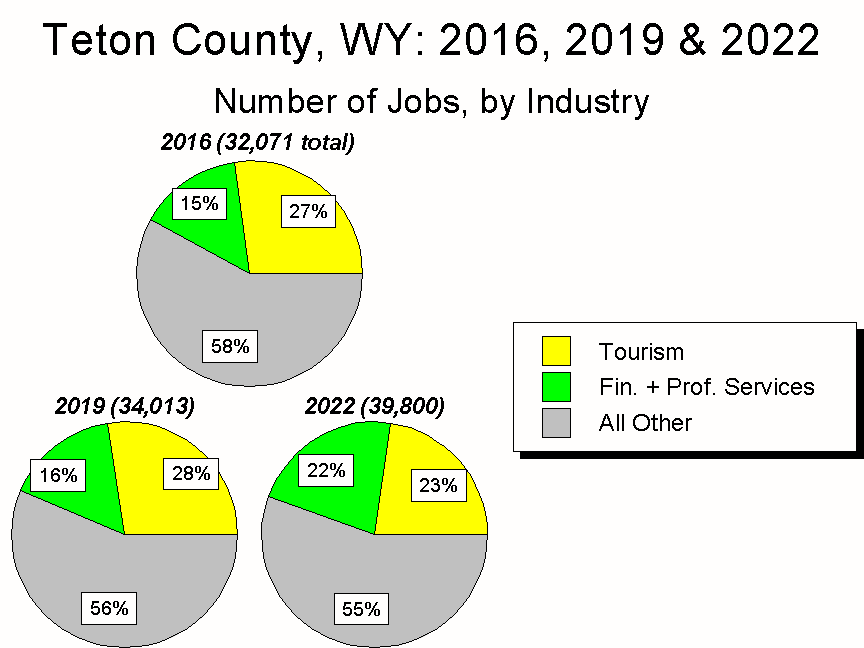

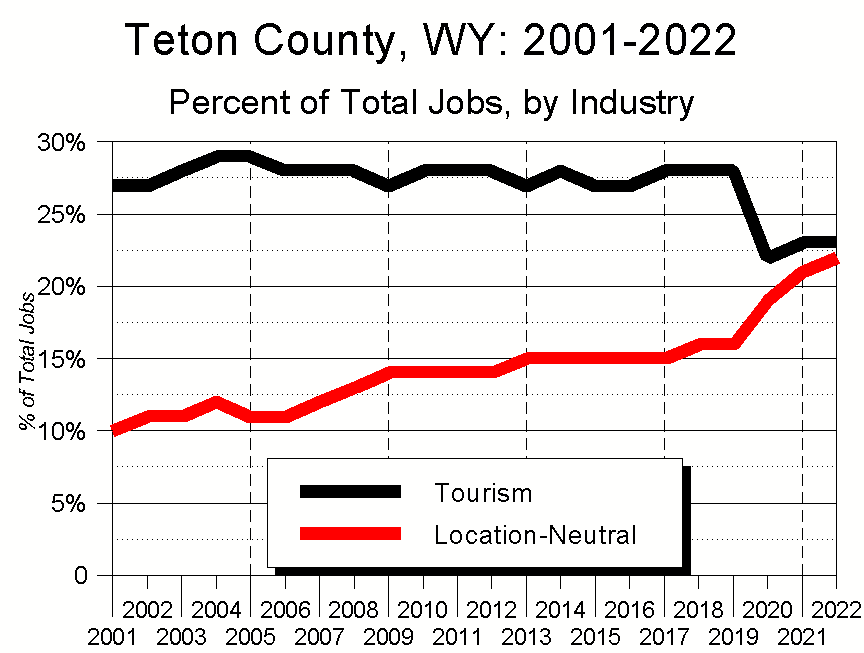

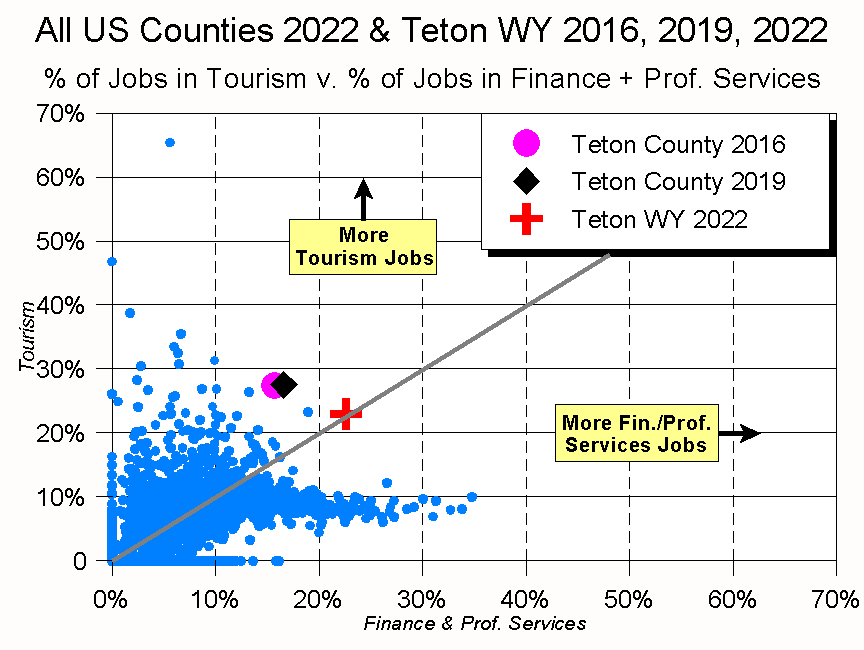

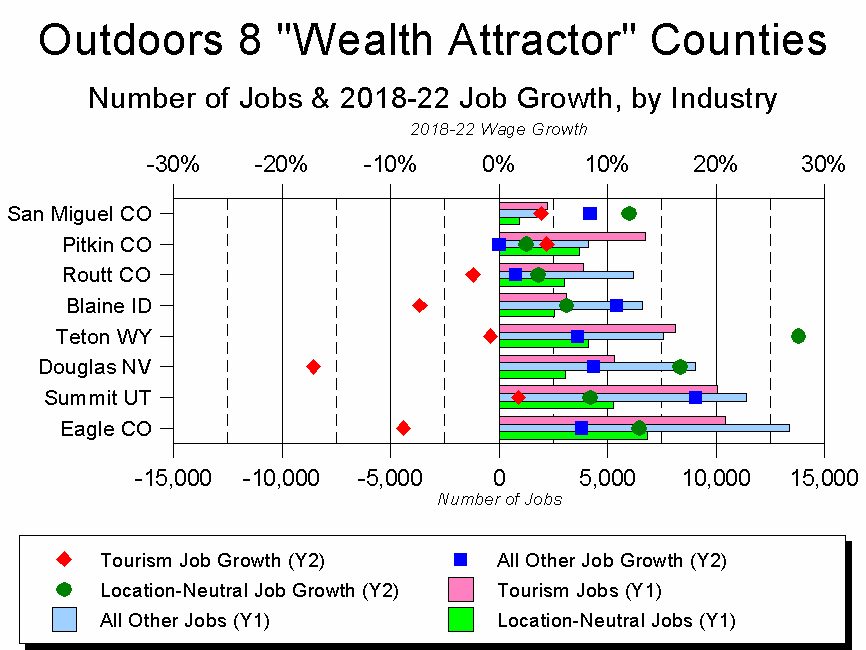

Where did the newcomers’ wealth come from? In part, from a shift in the counties’ job mix. Between 2018-2022, five of the Outdoors 8 saw a decline in Tourism-related jobs (i.e., jobs in recreation, lodging, and restaurants), and no county saw more than a 4% increase in Tourism jobs.

At the other end of the spectrum, in five of the Outdoors 8 the biggest job growth occurred in the “Location-Neutral” industries of Information, Finance, and Professional Services. In the remaining three, Location-Neutral jobs were the second-fastest area of growth. (Figure 7)

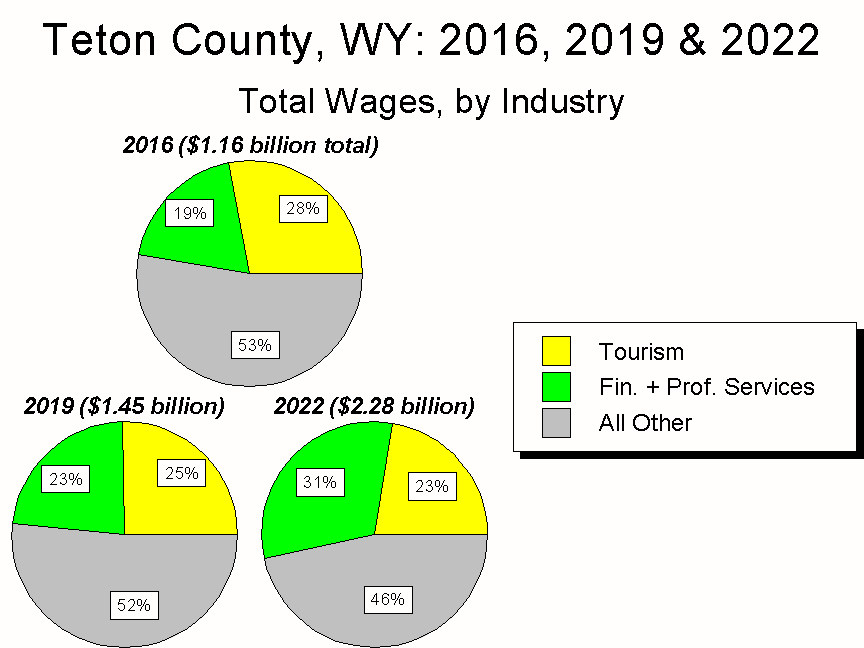

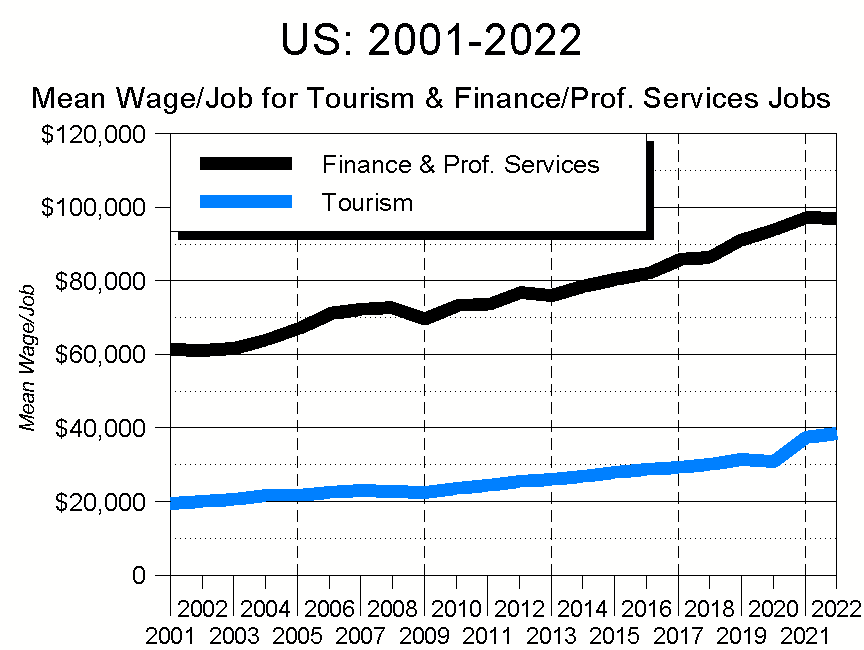

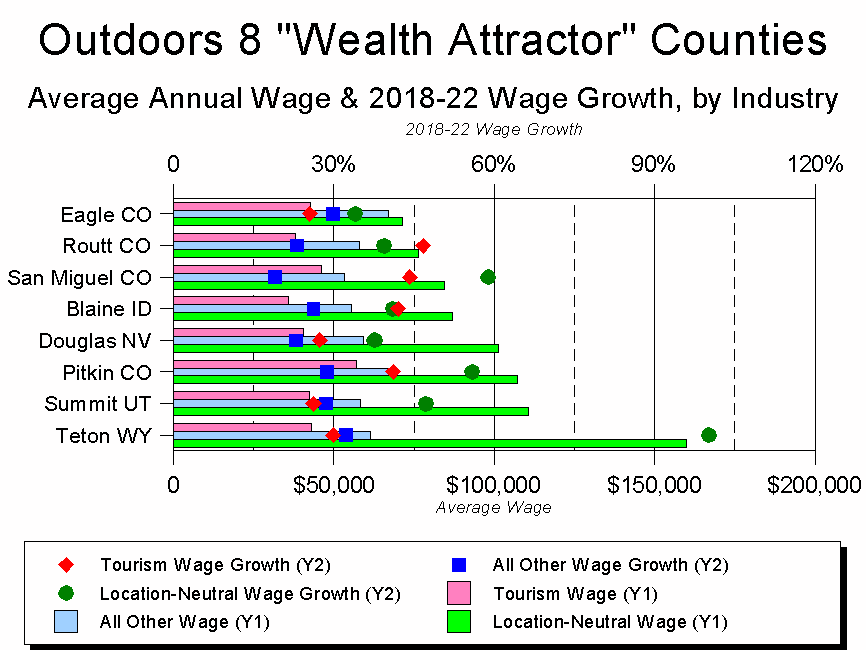

This job mix matters because not only do Location-Neutral jobs pay far more than Tourism-related jobs, but Location-Neutral wages are going up far faster than in any other field.

The result is a weird anomaly: In 2022, the Outdoors 8 had 70% more jobs in Tourism than in Location-Neutral industries, but the Location-Neutral payroll was 40% higher.

Perhaps even more important is the fact that not only are wages in Location-Neutral jobs two-to-three times higher than those in Tourism, they are growing much faster.

The point? Between 2018-2022, job and wage growth in the Outdoors 8 were driven by Location-Neutral industries – folks who could work anywhere chose to work in places emphasizing nature and outdoor recreation.

Further, when Location-Neutral businesses pay, on average, over twice the wage paid by a Tourism-oriented job, it suggests that those running Tourism-oriented businesses are going to be facing an increasingly difficult time finding employees. (Figure 8)

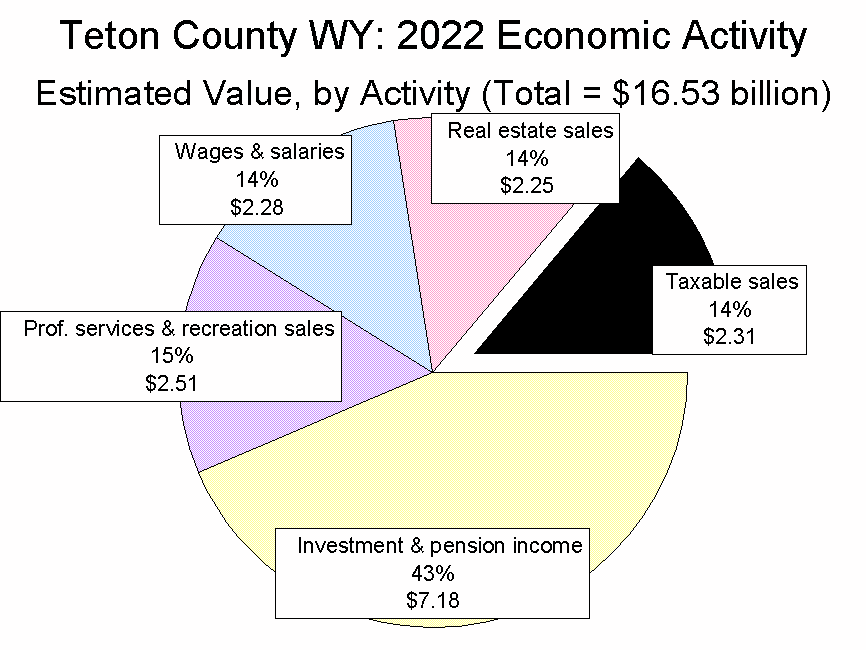

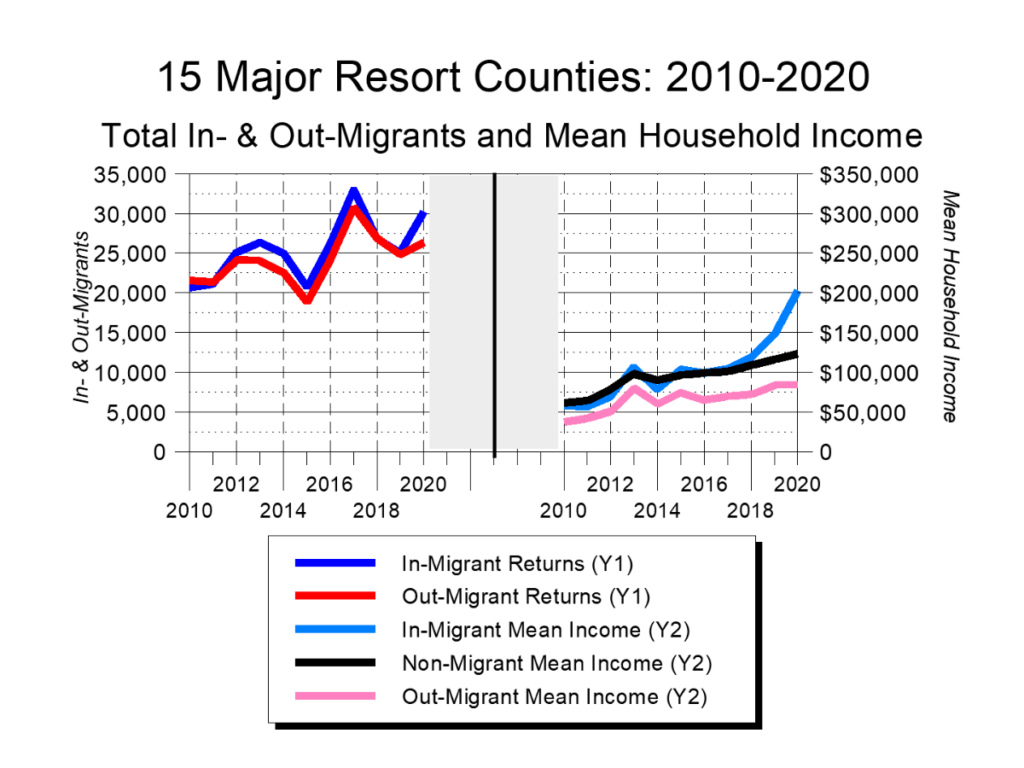

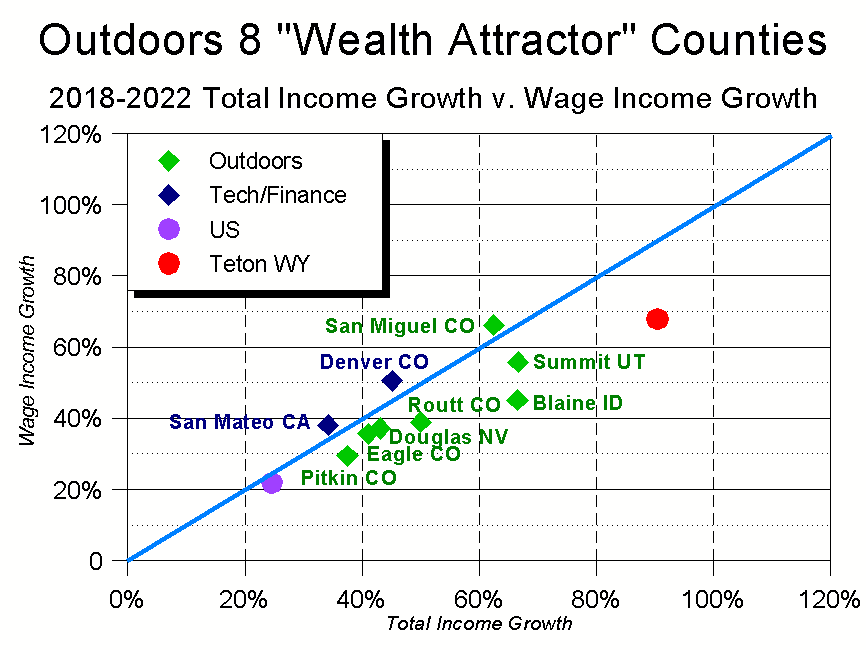

For as well-paid and bountiful Location-Neutral jobs may be, though, they are NOT what drove the rapid increase in the Outdoors 8’s overall incomes. In particular, as Figure 9 shows, seven of the Outdoors 8 saw their overall incomes grow faster than their wage incomes (this is why they are to the right of Figure 9’s blue line, which indicates equal growth between wages and total income).

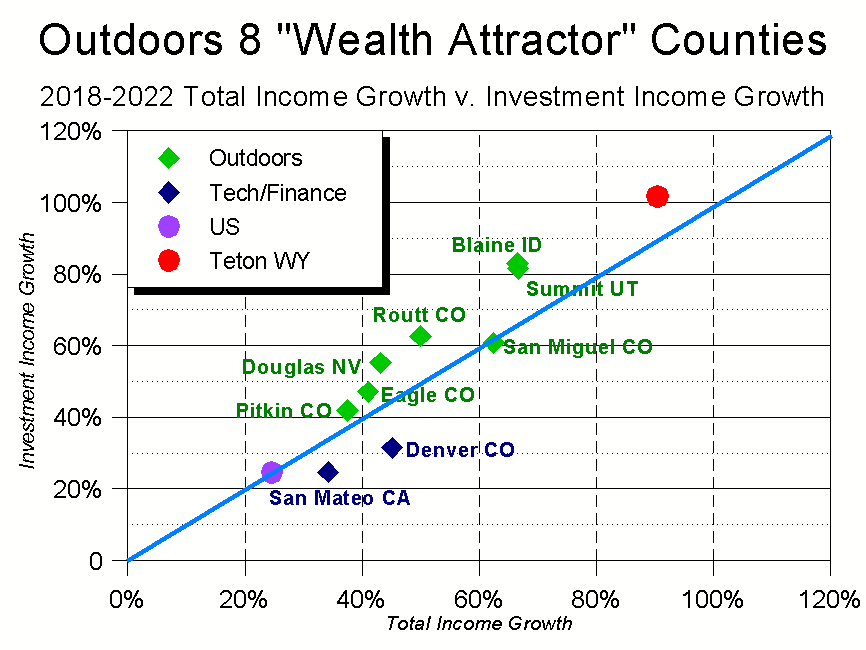

So what drove Outdoor 8 residents’ growth in personal income? In a word, investments, that most location-neutral of all income types. Figure 10’s X axis is the same as Figure 9’s; i.e., it shows 2018-2022 growth in Total Income. Figure 10’s Y axis is different, though, substituting Investment Income for Figure 9’s Wage Income. As Figure 10 shows, again with the exception of Telluride, between 2018-2022 every Outdoors 8 county saw its Investment Income grow faster than its Total Income. The two Tech/Finance counties experienced the opposite. (Figure 10)

The bottom line is that in 2022, even in the most wage-dependent of the Outdoors 8 counties, residents got at least 41% of their overall income from investments; in five of the eight, investments accounted for over half of residents’ total income. In the US as a whole, only 20% of Americans’ total income comes from investments.

Further, between 2018-2022, in six of the eight counties Investment Income was the fastest-growing type of income. Combine this with the huge surge in Location-Neutral wages, and a very clear picture emerges that during the COVID era, people with the economic freedom to move where they wanted to go chose mountain towns closely connected to the natural world around them.

The same was distinctly NOT true in previous cycles, where rapidly growing incomes were closely tied to a particular type of work. (Figure 11)

Comment

To me, Table 1 (above) captures the most important finding of this study, namely that the COVID years marked a distinct change in how we think about economic boom towns. In turn, I think that has clear implications for the future of Jackson Hole and other communities where the character, economy, and quality of life are closely tied to the natural world around them.

Specifically, my big takeaway from Table 1 is that before the COVID years, places experiencing rapid income growth – i.e., boom towns – were associated with a particular type of industrial growth. In the mid-2010s, the tech boom shot Silicon Valley’s incomes to new heights. Four years earlier, the boom was in hydrocarbons, particularly those extracted by fracking. Hence those counties’ surge in income.

This phenomenon is captured in Table 2, which takes Table 1 back four more years. During that 2006-2010 period, eight of the ten biggest Wealth Attractor counties were in western North Dakota, the epicenter of the fracking boom. (Table 2)

Things changed with COVID, however. All of a sudden, traditional economic drivers were no longer associated with counties’ growth in wealth. Instead, for those people who had the flexibility in their incomes, the attractor was nature, authenticity, and no doubt a sense that a relatively remote place would offer a sense of safety from COVID they could not find in major cities.

Put another way, before 2018-2022 America had never seen such an explosion of wealth associated with places prioritizing conservation of the natural world. Going forward, though, economists will have to consider the dynamics of not just boom towns associated with oil or gold or software, but those associated with conservation and lifestyle.

This raises two obvious questions: “Will this shift last?” and “Whether or not it does, what are its implications for the Outdoors 8?”

Regarding “Will this shift last?” that is an open question. Using the methodology underlying Tables 1 and 2, I looked at four-year cycles going back to 1970-1974. To generalize, for nearly 50 years, Wealth Attractor counties fell into one of three categories:

- Low population, agriculture-intensive economies during a period of high commodity prices;

- Low population, hydrocarbon-intensive economies during oil and gas booms; or

- Finance and/or tech hubs during financial and tech booms

During that time, the only real exception to this rule occurred between 1998-2002, when four outdoors-oriented counties ranked among America’s ten leading Wealth Attractors: the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, and the ski towns of Steamboat Springs and Telluride. Because this period straddled 9/11, the surge in wealth experienced by these communities suggests that folks who could afford to do so flocked to a place of perceived safety.

Arguably, the same thing happened between 2018-2022, when COVID led many Americans to search for a different type of safety.

Taking a longer-term view, however, here’s what hit me.

As the sea of pink in Table 2’s first two columns suggests, the primary wealth attractor between 2006-2014 was hydrocarbons, in particular the wealth that was available through fracking in North Dakota’s Bakkan Field. That boom faded, though, and between 2014-2018 was replaced by the huge surge in wealth created in Silicon Valley. In turn, as things in tech slowed down, that boom was replaced by a surge that was more about lifestyle than economic opportunity.

Will well-to-do Americans keep flocking to places like the Outdoor 8? Hard to say, because we’ve never seen a boom like it. We also don’t know the degree to which places like the Outdoors 8 will “deplete” the resource underlying their boom by failing to conserve the natural world around them.

Regardless, there’s a larger lesson here, namely how booms continue to affect communities long after they’ve slowed down.

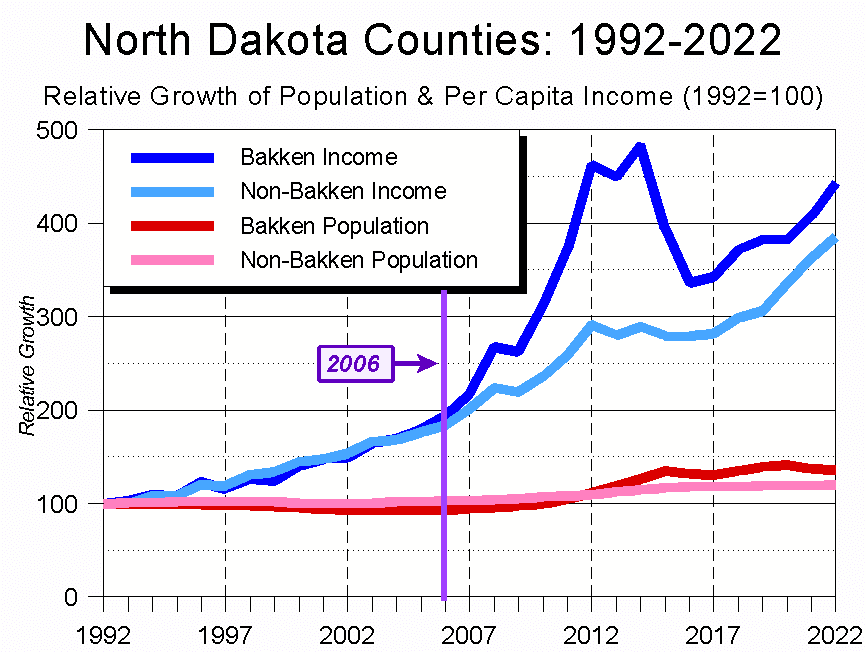

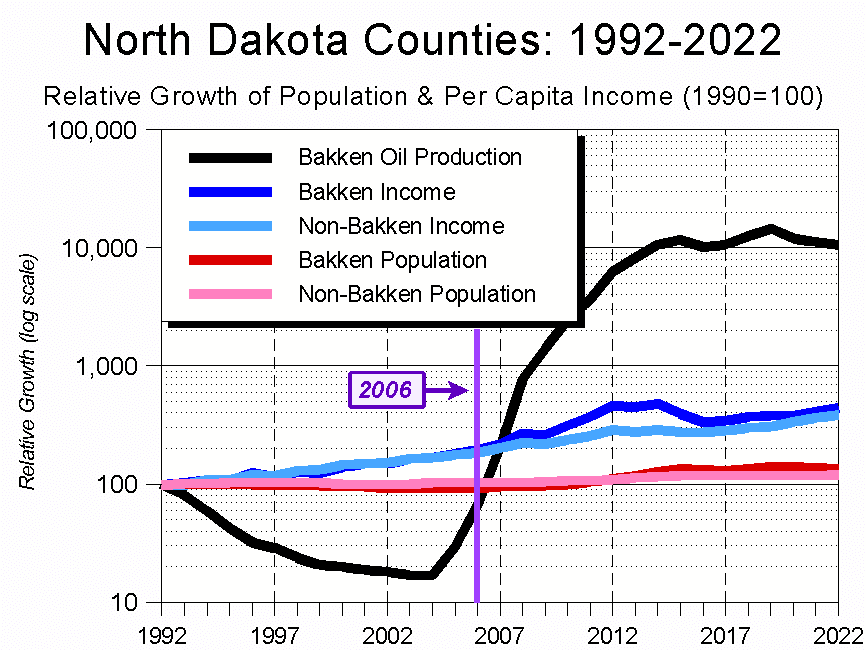

For example, consider the eight North Dakota counties that form the heart of the Bakken region. From 1992 to 2006, their per capita income growth matched that of North Dakota’s other, non-Bakken counties, and their population growth was slower. In fact, in 2010 the Bakkan counties’ population was actually lower than it had been in 1992. (Figure 12)

Today, however, the Bakkan counties’ per capita income is significantly higher than the rest of the state’s, and since 2010 their population growth has been three times faster than the rest of North Dakota’s.

Why? Because the effects of the Bakken field boom that started nearly two decades ago continue to reverberate today. In particular, even though the huge boom in drilling petered out over a decade ago, North Dakota’s Bakken counties have not declined to their pre-fracking selves. Instead, they have settled into a post-boom “new normal,” one highlighted by faster population growth and a per capita income significantly higher than the rest of the state. (Figure 13)

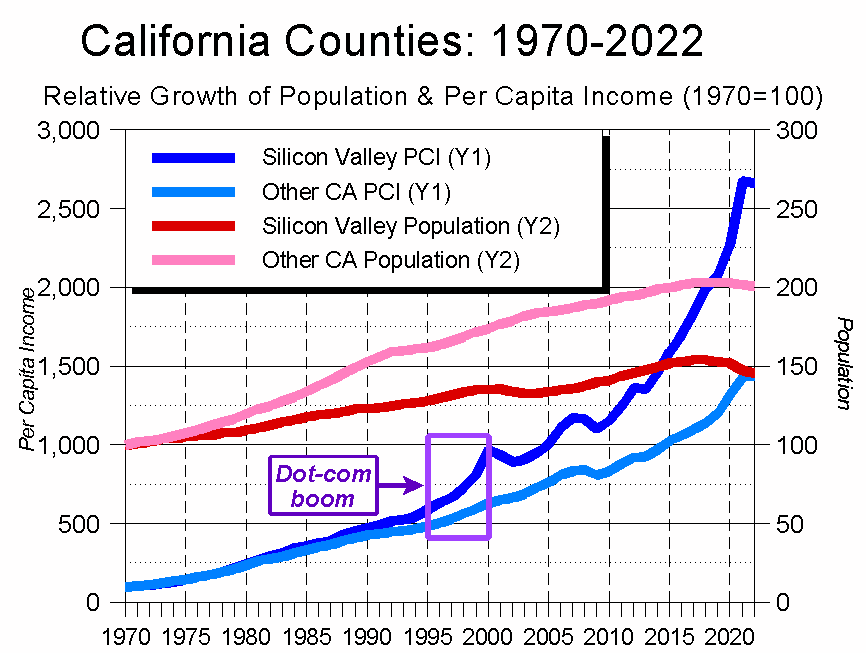

A similar dynamic occurred in the Bay Area a decade earlier, when the dot-com boom separated the economic trajectory of the three Silicon Valley counties of Santa Clara, San Francisco, and San Mateo from that of the rest of the state. Despite the 1990s’ dot-com boom going bust, incomes in the Silicon Valley were boosted to a new floor, one upon which all future growth has been based. (Figure 14)

Conclusion

During COVID, Teton County and similar communities experienced a boom of their own, albeit one driven by a very different mechanism: setting and lifestyle rather than traditional economic drivers. Whether the Outdoors 8 and related places will continue to rank at the top of America’s Income Attractor list isn’t clear. What seems likely, though, is that as with the hydrocarbon- and tech-driven booms, the shifts that occurred during the COVID years will continue to reverberate going forward.

As I see it, the thing tying together Apple’s virtual reality headset, the Icon of the Seas, and Las Vegas is that they are all sugar highs, activities which create adrenaline rushes. While I am not a neuroscientist, the reading I’ve done suggests the problem with adrenaline rushes is habituation; i.e., over time, you need a bigger jolt to get the same feeling. Hence Las Vegas has to keep adding new attractions, cruise ships have to keep getting bigger and, oxymoronically, virtual reality has to keep getting more real.

Alternatively, by going out in nature you can experience actual by-God reality, things our species has evolved to appreciate over hundreds of thousands of years. This type of experience involves a different sort of neural reaction, one that is more profound and less sugar-high.

It’s for this reason that I think the migration to communities like the Outdoors 8 will continue. Maybe not at the same pace as during COVID, but continue nonetheless. Technology has made geographic barriers increasingly less meaningful, allowing those with economic freedom to live where they want to live rather than where work forces them to live. And while the trendiness associated with living in a community closely tied to nature will wax and wane, the deep neural connections won’t. In that way, the incentives pulling people to places like the Tetons are far less susceptible to booming and busting because, at the end of the day, they aren’t purely – or even primarily – economic. Instead, they’re about something more intrinsic to humans’ essence.

From a Maslow’s hierarchy perspective, America’s extraordinary economic success has made it increasingly easy for people to pursue their higher selves. One result is the kind of shift that occurred between 2018-2022, when for the first time in the nation’s history there wasn’t a simple economic explanation underlying America’s leading Wealth Attractor counties. To me, that suggests we need to consider anew many of the foundational assumptions underlying where we think Jackson Hole and related communities are heading, as well as how we deal with that future.

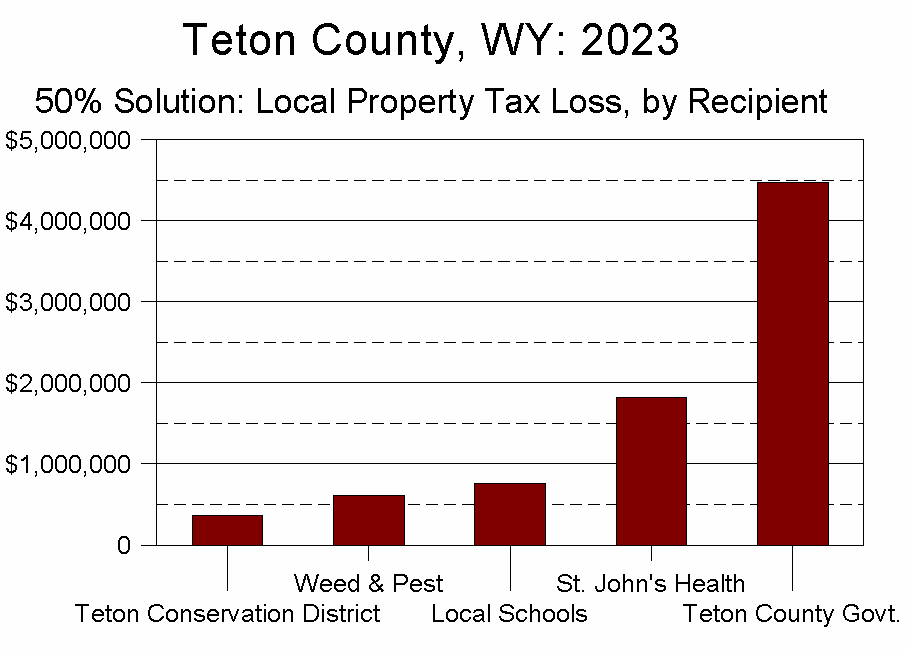

What will this mean for Jackson Hole? My best guess is that the pressures we were feeling before COVID, and which COVID only accelerated – pressures including affordable housing, governmental budget challenges, growing income inequality, and increasingly stressed infrastructure and ecosystem health – will become even greater.

Less clear to me is how we will handle those pressures.

Historically, our sense of community – that ineffable something that has bound residents together despite our disagreements – has allowed us to weather even the thorniest of challenges and still emerge with a sense that we are greater than the sum of our parts.

What concerns me, though, is whether another one of the things COVID has upended is our sense of community. Have the pressures become so great and the tensions so sharp that we’ve lost sight of that which binds us together, namely our shared sense that we are stewards of an extraordinary place, a place which never fails to produce awe in those who experience it?

Clearly social media and economic pressures have led to a coarsening of civil discourse. Sadly, COVID only made things worse. My fervent belief, though, is that we as a community can rise above that negativity; that we can recognize in each other the fact we’re all here for the same basic reason. As I see it, that foundation is far stronger than anything our discordant world can throw at us. Why? Because unlike the cheap sugar highs of virtual reality, it is intrinsically connected to the natural world around us.

That’s why people will continue to be attracted to places which have put a premium on conservation. It’s also why the entire Tetons region – along with every other place which emphasizes the natural world around it – can anticipate continued growth pressures, particularly from those with the economic freedom to live where they want to live. The key to addressing those pressures will be to not lose sight of why we’re here, to not let the noise associated with our community’s growth and change overwhelm the signal that is the conservation and stewardship legacy we inherited from our forebears, and which we in turn must protect for future generations.