Hello, and Happy almost-New Year!

It’s the time of year when the media feature pieces like “This Year’s Biggest Stories” and “The Best of 2023.”

Along these lines, in this newsletter I’d like to explore an issue I’ve not only heard a lot about, but which is inexorably shaping Jackson Hole’s future: property taxes.

My point of departure is an observation that may seem counter-intuitive: For a growing number of residents, Jackson Hole is a land-rich, cash-poor community.

This land/cash disconnect is manifesting itself most clearly in the challenges posed by skyrocketing property taxes. In particular, while rising property values have left all property owners much wealthier on paper, that wealth can’t be realized until the property is sold. In the meantime, property owners have to pay taxes out of their income, which for most people isn’t growing as fast as their taxes.

The result is a lot of people increasingly afraid that rising property taxes might force them to sell their homes.

And it’s not just Jackson Hole. Across Wyoming, property taxes are rising. Not as much as in the Tetons, where we “enjoy” the state’s highest property values. But the same taxes-growing-faster-than-wages phenomenon has begun affecting communities across the state.

What to do?

Proposals to cap or freeze property taxes abound. These conversations are similar to ones that occurred in California in 1978, when anger over rapidly rising property taxes led voters to pass Proposition 13. Prop. 13 did a bang-up job capping property tax growth for those who already owned property, but weirdly distorted things for future buyers. Far worse, it wreaked havoc on government finances, leading to major funding problems for education and local government services.

Forty five years later, I’d hate for Wyoming to repeat California’s mistakes. As a result, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about different ways local government might levy property taxes. The idea described below, which I call the MOTH, would help address the land-rich/cash-poor dilemma by effectively eliminating town and county property taxes on the least valuable 50% of Teton County properties, and lowering them on the next 15%.

In the process, the MOTH would also produce more revenue for local government. In turn, those funds would help mitigate the difficult choices the community must soon make regarding what services local government can afford to provide.

If adopted, would the MOTH fully address Jackson Hole residents’ growing property tax burdens? Nope – not even close. This is because the MOTH would apply only to the property taxes levied by the county and town, which collectively account for just one-eighth of property owners’ tax bills (most property tax revenue goes to fund public education).

That noted, the MOTH would still benefit a lot of folks, especially those most in need of help. It would also help every year going forward, because by design it automatically shields the county’s lower-value properties.

More importantly, simply discussing the MOTH will help the community in two additional ways.

First, it will trigger a dialogue about who we are and where we’re going. Right now, rapidly rising property values and their attendant taxes are changing Jackson Hole into a very different place than it’s been. Is this new Jackson Hole what the community wants? If not, what might we do? To me, that’s a conversation worth having.

Second, I’m concerned that people are losing confidence in government’s ability to address our challenges. Worse still, they’re losing confidence that government is even listening to them. From that perspective, if the MOTH can offer folks a sense that someone in office is at least aware of their concerns, that would be great. Better still will be if we can collectively take steps to address those problems.

- Introduction

- Property Taxes – Mechanics of the Current System

- Property Taxes – Their Role in Government Funding

- Property Taxes – Why They Exploded

- Property Taxes – Why Folks Are Hurting

- Property Taxes – An Alternative Approach (Enter The MOTH)

- The MOTH – Effects on Taxpayers

- The MOTH – Effects on Local Government

- Comment

From my family to yours, may your 2024 be filled with abundant joy, great happiness, and deep contentment.

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

Introduction

This essay offers an alternative approach to levying local property taxes in Jackson Hole.

The alternative would make two fundamental changes to the current system:

- Maximize the property tax rates charged by Teton County and the Town of Jackson.

- Automatically reimburse taxpayers an amount based on the median value of their property type.

Because this new approach focuses on median property values, I call it the “Middle of the Hole,” or MOTH. If adopted, the MOTH would produce two significant outcomes:

- 50% of all property owners would pay no property tax to the town and county, and another 15% would pay lower property taxes than they currently do.

- Local government would receive more property tax revenue than it currently does.

This essay begins by describing the current situation: how property taxes are levied, why they’re important, and the problems they’re causing. Following a description of the MOTH’s mechanics and practical effects, the essay finishes with a few observations about the MOTH’s broader implications.

Property Taxes – Mechanics of the Current System

Property types

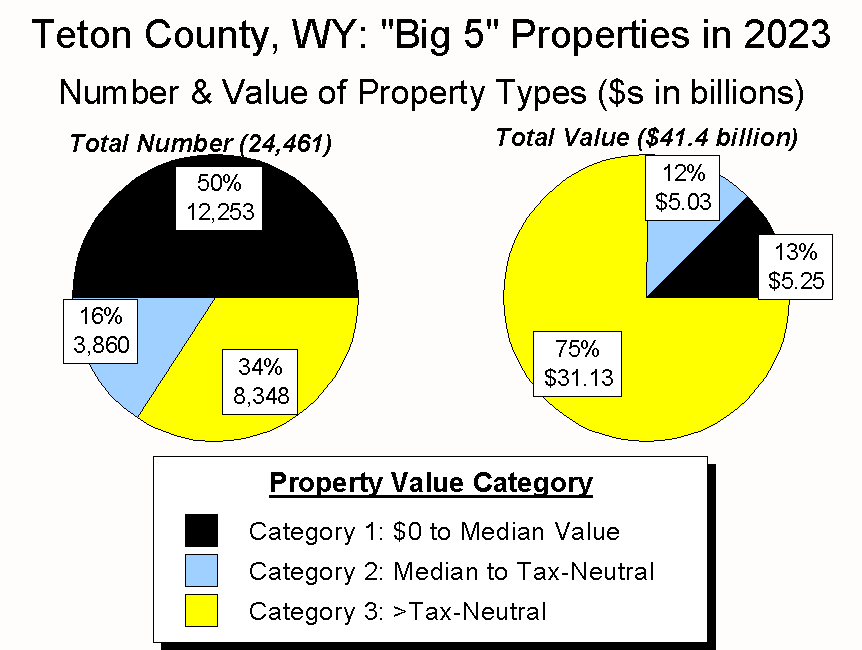

The State of Wyoming levies taxes on 12 types of property. Five types of property (the “Big 5″) account for 93% of the total number of properties and 99% of their total value:

- Residential Land (the land on which a home sits);

- Residential Improvements (the dwelling itself);

- Vacant Land (residential land which has no structures on it);

- Commercial Land; and

- Commercial Improvements.

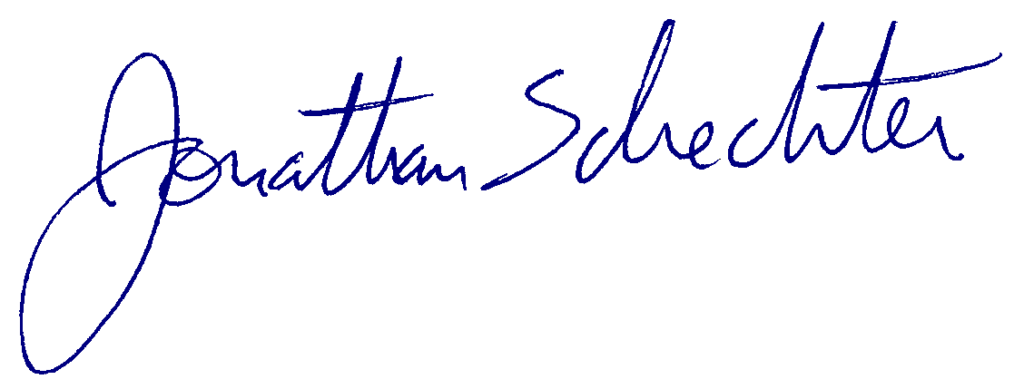

Teton County currently has 26,411 total taxable properties. Drilling down, the three residential property types – Residential Land, Residential Improvements, and Vacant Land – account for 83% of Teton County’s total number of taxable properties, and 88% of their total value. In this way, residential property is to Jackson Hole what hydrocarbons are to the rest of Wyoming: our biggest source of wealth. Unlike minerals, though, residential property can be “mined” over and over and over again. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Levying property taxes

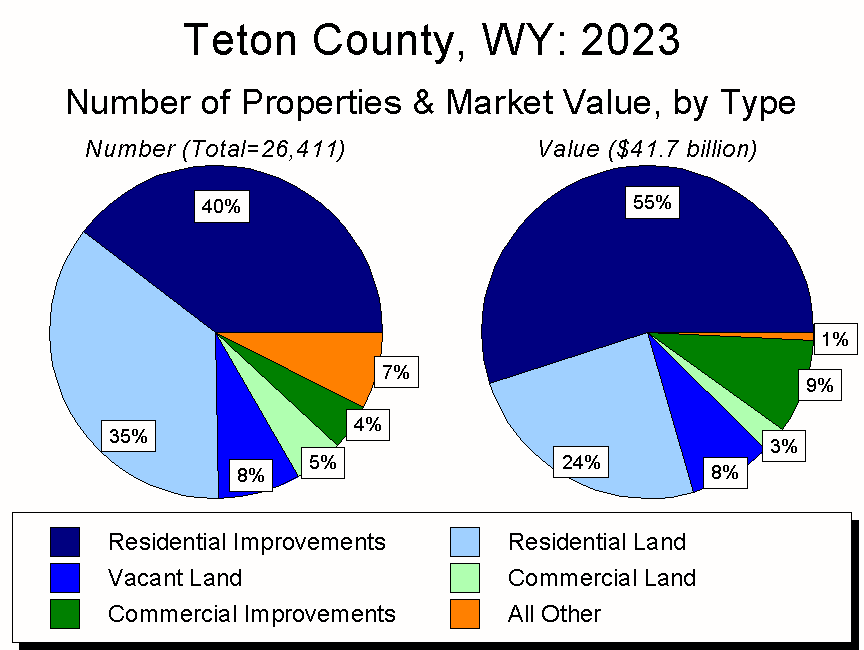

Levying taxes on the Big 5 is a three-step process.

Step 1: Estimate Market Value

In each of Wyoming’s counties, the assessor estimates the Market Value of each taxable property. By law, a property’s estimated market value must be within 5% of its actual market value.

Step 2: Calculate Assessed Value

Also by law, once the Market Value is determined it is multiplied by 0.095 (9.5%) to determine the Assessed Value.

Step 3: Levy Property Taxes

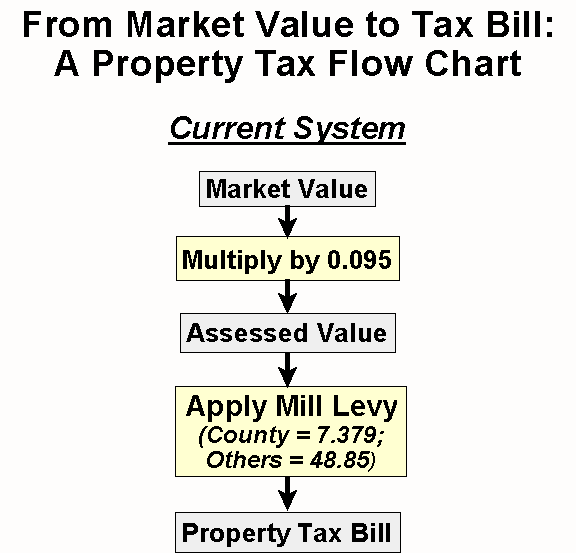

Property taxes are based on Assessed Value and levied in mills (a mill is one-thousandth of a cent.). Because Teton County’s 2023 base tax rate was 56.229 mills, this year a property worth $1 million would owe $5,342 in taxes. (Figure 2)

Figure 2

In Teton County, 79% of a property’s base tax payment funds public education. Thirteen percent funds local government, and the remaining eight percent goes to a combination of St. John’s Health and the county’s two public conservation efforts: Teton County Weed & Pest and Teton Conservation District.

Two things are notable about the 79% that funds public education:

- Essentially all of the education-related mill rate is set by the state; and

- Most of the proceeds go into a pool that funds public schools statewide.

For decades, Teton County received more money back from the statewide pool than we paid in. Because of our rapidly-rising property values, though, today we pay in more than we receive.

Teton County’s government currently levies 7.379 mills out of the 12 it can legally charge. Of that, ½ mill is earmarked for Fire/EMS. For properties in town, this ½ mill goes to the Town of Jackson to fund its share of Fire/EMS. Currently this is the only property tax the town levies. (Figure 3)

Figure 3

Property Taxes – Their Role in Government Funding

Teton County and the Town of Jackson have three basic sources of general fund revenue: sales taxes, property taxes, and “all other.”

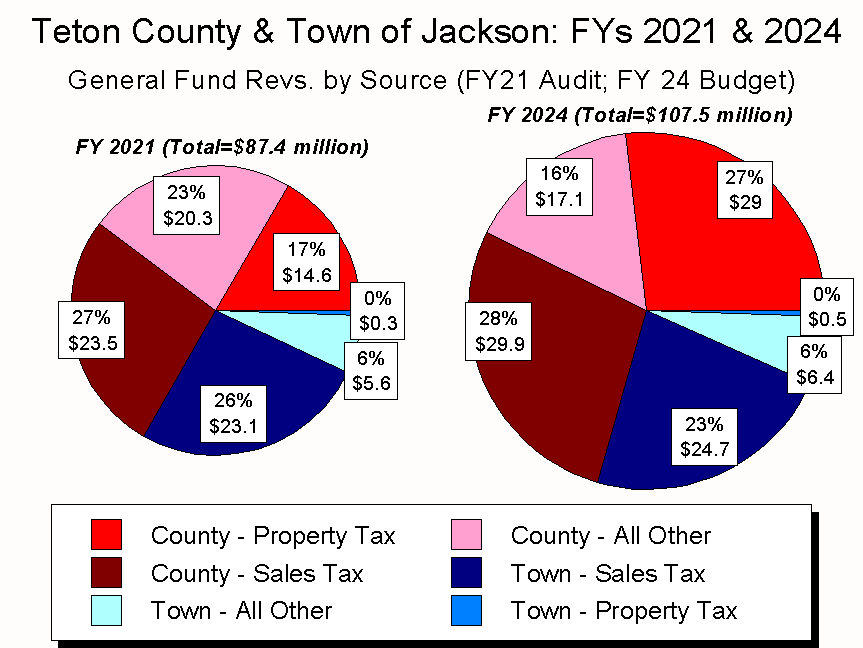

All Wyoming governmental entities have a July 1 fiscal year. In FY21 – i.e., the first full year of the COVID pandemic – Teton County and the Town of Jackson had combined general fund revenues of $87.4 million. This year, their budgeted general fund revenues total $107.6 million, a $20.2 million increase (23%) over FY21.

Of the $20.2 million increase, $14.6 million (72%) came from property taxes, with the rest coming from a variety of other sources. $200,000 of the $14.6 million went to the Town of Jackson, and the rest to Teton County’s government.

Sales taxes are the largest source of income for local government. In FY21 sales taxes accounted for 53% of local government’s combined general fund revenues, and property taxes accounted for 17%. This made for a 3.1 to 1 ratio of sales tax revenue to property tax revenue.

In FY24, sales taxes will account for a similar amount of local government’s total general fund revenues: 51%. Because of the sharp rise in property taxes, though, in FY24 property taxes will account for 27% of all local government general fund revenues. This makes FY24’s sales-tax-to-property tax ratio 1.9 to 1. (Figure 4)

Figure 4

Property Taxes – Why They Exploded

For two reasons, 2020 marked a turning point for Jackson Hole’s property tax situation.

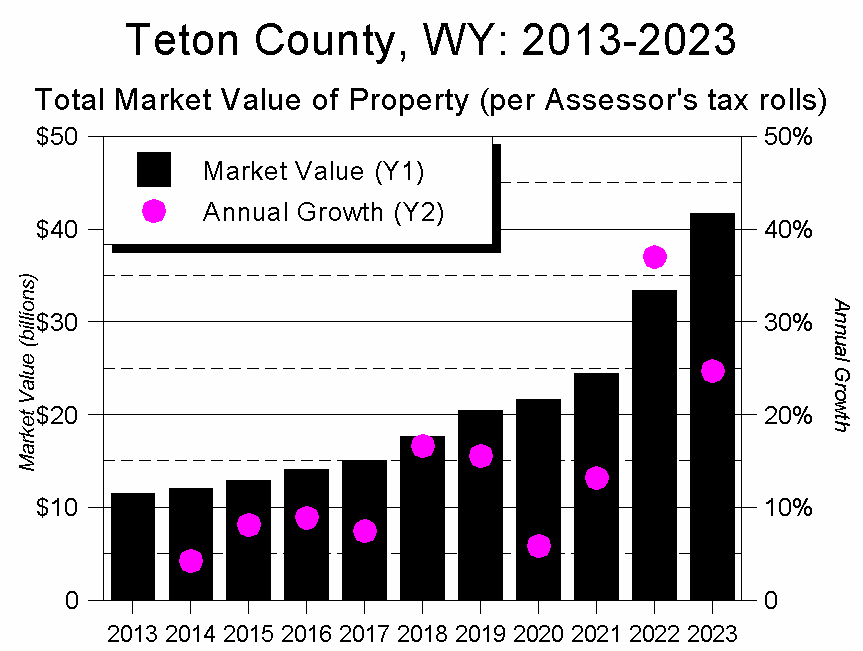

First, as noted above, under Wyoming law the County Assessor’s estimated market value of a property must be within 5% of its actual market value. For a variety of reasons, though, through the mid-2010s Teton County’s estimated market values were well below actual market value. As a result, about 10 years ago the state said “Fix it.”

Bringing all of Teton County’s properties up to market value took a couple of years. That resulted in the double-digit property value increases that occurred between 2017- 2019.

Once the re-valuation process was finished, the growth rate returned to earlier levels. Just as that dust was settling, though, COVID hit, and the ensuing flood of pandemic in-migrants drove Jackson Hole’s property values to previously unimaginable heights. As a result, between 2021-2023 the total value of all Jackson Hole properties rose by 71%, twice as fast as 2017-2019’s then-record increase.

Because property taxes are based on property values, the COVID-induced demand for Jackson Hole homes resulted in the recent property tax explosion. (Figure 5)

Figure 5

Property Taxes – Why Folks Are Hurting

In 2013 the median value of all of Teton County’s residential properties (both land and dwellings) was $273,559. Today it’s $1,005,760 – an average annual growth rate of 14%.

In 2013, Teton County’s average annual wage was $38,012. Today it’s $74,412, an average annual growth rate of 7% – half that of property values.

Most of the growth in property values has occurred during the past couple of years. Between 2021-2023, property values grew 30%/year, while wages grew 11%/year. Because property values drive property taxes, over the past couple of years Teton County’s property taxes have risen three times faster than its wages.

Some people have been unable to afford this rapid increase in property taxes. Others have been able to afford it so far, but won’t be able to if property taxes continue to grow faster than wages. Still others may be able to afford the increases in property taxes but may not want to. These folks are asking themselves questions like: “Is living in Jackson Hole worth the extra money I’m paying each year in property taxes?”

For each of these groups, moving away from Jackson Hole has become something between a necessity and an increasingly plausible option. That’s a cruel fate for people who don’t want to move, especially long-time residents who have helped create a place the well-to-do are finding so desirable. Yes, many of these long-time residents will enjoy a huge financial windfall when they sell. But what if they don’t want to sell? Being forced to move for the sin of suddenly finding themselves land-rich and cash-poor is a cruel reward for their extraordinary stewardship of the community.

Property Taxes – An Alternative Approach (Enter The MOTH)

To state the obvious, when it comes to taxes it’s important to treat everyone equitably. Currently, Teton County and the Town of Jackson do that by levying the same number of mills on all property, regardless of value.

There is another way to approach the issue, though; one that also treats everyone equally but produces different outcomes for both taxpayers and local government.

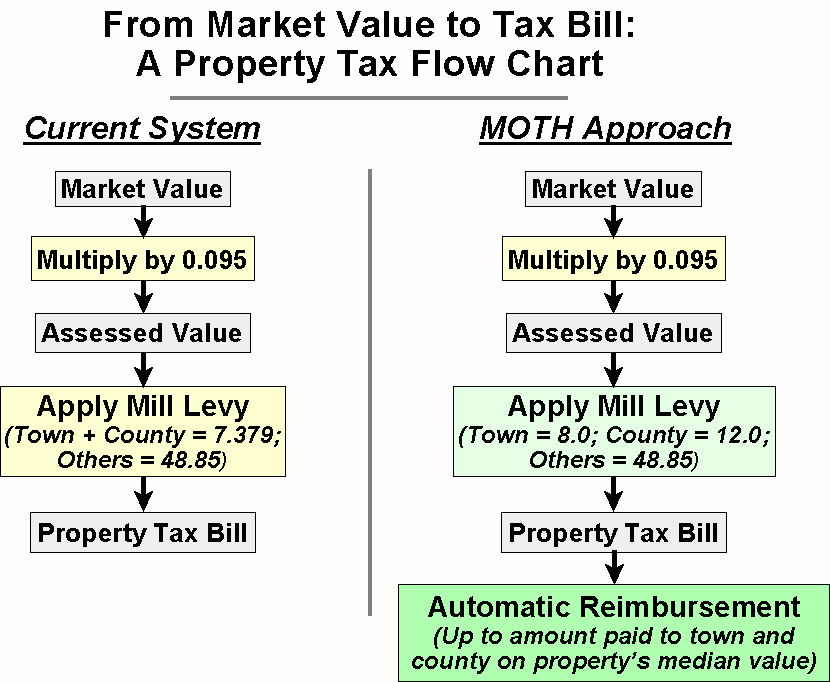

The MOTH differs from the current approach to property taxes (the “Current System”) in two key ways:

- The MOTH raises the property tax mill levy to the full amount allowed under Wyoming law. Specifically, Teton County’s levy would go from its current 7.379 mills to 12; the Town of Jackson’s would go from its current 0.5 to 8.

- Upon paying their property taxes, each taxpayer would immediately be reimbursed the tax paid to the town and county, up to the amount levied on the median-value property of that type. (Figure 6)

If enacted, the MOTH would result in 50% of all property owners paying no property taxes to local government, another ~15% paying lower property taxes than they do now, and ~35% paying higher taxes.

(Note: Rather than have someone pay their taxes and then be reimbursed, it would be easier to simply not pay the reimbursed amount. Unfortunately, under Wyoming law the more straightforward approach isn’t legal, while the reimbursement approach is.)

Figure 6

For an example of how the MOTH would work, consider a Residential Improvement (i.e., a dwelling, but not the land it sits on) in the unincorporated county.

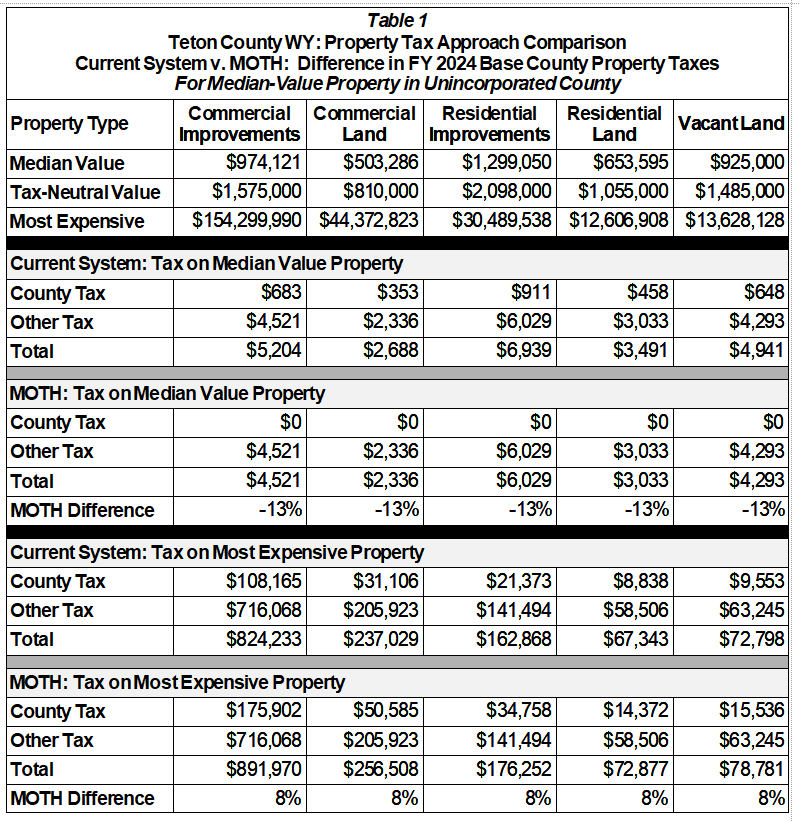

In 2023, the median value of all of Teton County’s Residential Improvements was $1,299,050. Currently, someone owning a Residential Improvement worth that amount pays Teton County’s government $911/year in property taxes.

Under the MOTH, the county’s mill levy would go from the current 7.379 to 12, resulting in a $1,481 property tax bill. Once the county received that payment, though, it would automatically reimburse the property owner the same $1,481. As a result, the property owner’s net tax payment would be $0.

Anyone owning a property worth less than the median value would be reimbursed the entire amount they paid the county in property taxes. Anyone owning a property worth more than the median would receive $1,481 back from the county. For about 15% of all taxpayers, that would result in them paying something, but less than what they would pay under the Current System. For the remaining 35%, their property tax bill would be higher than it currently is.

The MOTH – Effects on Taxpayers

The median is the number in the middle of a data set; i.e., half the values fall below the median and half above it.

Because the MOTH is based on the median, under the MOTH half of all property owners would no longer pay any property taxes to local government. Let’s call these folks the Category 1 taxpayers.

Category 2 taxpayers would pay some property tax, but not as much as they do under the Current System. Using the Residential Improvements example from above, Category 2 taxpayers would be those with a dwelling valued between the median value of $1,299,050 and the Tax-Neutral value of $2,098,000.

While the exact percentage would vary for each property type, around 15% of all taxpayers would fall into Category 2.

Category 3 taxpayers would be those owning the remaining, higher-end properties. Under the MOTH, these property owners would pay more in local property taxes than they currently do. Again using the Residential Improvement example from above, anyone owning a dwelling in the unincorporated county valued at more than $2,098,000 would pay higher property taxes under the MOTH than under the Current System.

(Note: Keep in mind that these examples include just the value of the dwelling, not the property on which it lies. There is a separate tax calculation made for Residential Land, which currently has a median value of $653,595. As a result, under the MOTH, a median-valued dwelling worth $1,299,050 sitting on a median-valued lot worth $653,595 – for example, a typical Rafter J house – would pay no local property tax. A Category 2 property owner (i.e., one paying no more than they do now) would be someone with a dwelling worth up to $2,098,000 on a lot worth up to $1,055,000 – think a home in Melody Ranch or the Aspens.

If you want to know the value of any particular property in Teton County, you can CLICK HERE to be connected to the endlessly interesting Teton County GIS server.)

The one-eighth we control

As noted above, the MOTH would apply only to the property taxes levied by Teton County and the Town of Jackson. Because those two entities combined levy only a fraction of all property taxes, if enacted the MOTH would not have a huge effect on any individual taxpayer.

For example, consider once again the median-value $1,299,050 Residential Improvement. Under the MOTH, the owner of that property would end up paying no net property tax to local government. They would, however, still have to pay all other property taxes. As a result, under the MOTH their overall property tax bill would be $911 less than under the Current System (13%). Not a huge amount, but for those on tight budgets every little bit helps.

At the most rarified end of the spectrum, the owners of the highest-valued dwelling in Jackson Hole (its Residential Improvements alone are valued at $30.5 million) would see their overall property tax bill rise 8%, from the Current System’s $162,868 to the MOTH’s $176,252. (Table 1)

The MOTH – Effects on Local Government

If adopted the MOTH would help local government in two ways: financially and politically.

Financial

Currently the highest-valued one-third of Teton County’s “Big 5″ properties account for three-quarters of the properties’ total value. Because of this, despite the fact that the MOTH eliminates or reduces local taxes on roughly two-thirds of all properties, its higher mill levies would result in more tax revenue for Teton County and the Town of Jackson. (Figure 7)

Figure 7

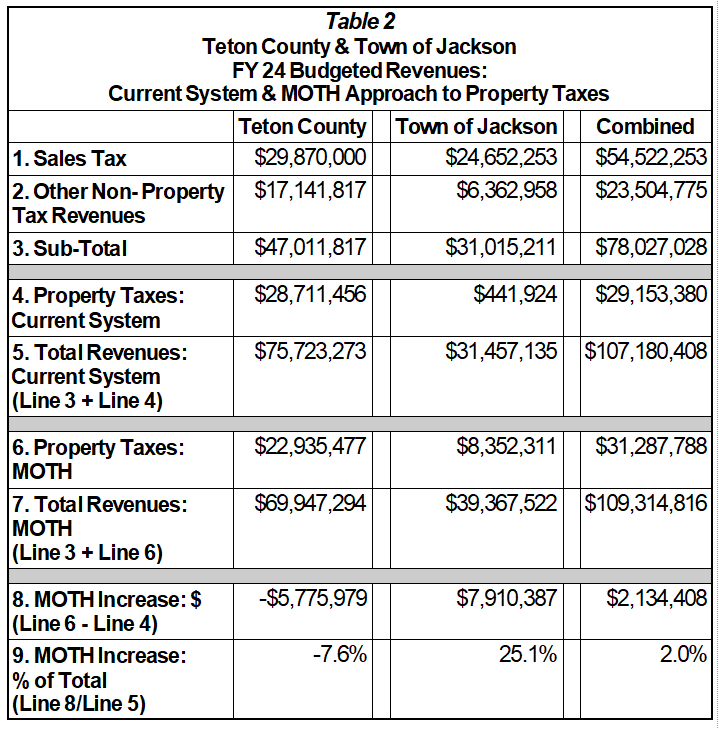

Putting specific numbers on this phenomenon, had the MOTH been in place this year Teton County and the Town of Jackson would have collectively received $2.1 million more in property taxes than under the Current System.

As Table 2 indicates, under the MOTH the town would take in more property tax money than it currently does, and the county would take in less. In the “Comment” section below, I address the obvious problem this creates.

Figure 7

Political

Over the past couple of decades, Teton County and the Town of Jackson have repeatedly tried to get the legislature to pass bills that would help Jackson Hole deal with its singular challenges. Some of these efforts have succeeded; most have not.

Particularly unsuccessful have been efforts to align Jackson Hole’s tax structure with its economy. For example, over the last five years real estate sales have exceeded taxable sales by $1.1 billion (12%). As a result, there’s a strong argument to be made for a real estate transfer tax. Yet like so many other efforts Jackson Hole has made, getting the legislature to approve such a tax has proven a non-starter. (Figure 8)

Figure 8

One reason the legislature gives for saying “No” is that Teton County and the Town of Jackson currently don’t utilize all the revenue-generating tools available to them, in particular property tax mills. If the MOTH were adopted, this objection would be neutralized.

Comment

The MOTH raises four issues that lend themselves to discussion: cost-shifting, revenue distribution, the nature of the community, and the role of local government.

Cost-Shifting

Like graduated income taxes, at its essence the MOTH is a cost-shifting mechanism: It decreases property taxes on less-expensive properties and increases them on more-expensive properties.

Underlying the cost shift is an assumption that, on balance, those who own lower-value properties have lower incomes and are therefore less able to afford sharp increases in property taxes. A related assumption is that those who own higher-value properties make more money, and are therefore better able to afford higher property taxes.

Since assumptions are never 100% correct, under the MOTH those still needing property tax relief could seek it from income-based property tax relief programs. In fact, the MOTH would make such programs more effective because fewer people would turn to them, leaving more money for those truly in need.

One other thing worth noting is that because the MOTH is based on median property values, its reimbursement levels will change along with property values. As a result, it will always benefit those owning less-expensive properties regardless of how property values fluctuate.

While all this describes the MOTH’s mechanics, it begs the larger question: Why change the current system? Any thoughtful debate will ultimately focus on two core issues: the nature of the community, and the role of government. Before discussing those, though, a quick word on distributing MOTH revenues between the town and county governments.

Revenue Distribution

As noted above, while the MOTH would increase local government’s overall property tax revenues by ~$2 million, it would do so unequally: had the MOTH been in effect this year, the town would have taken in $7.8 million more in property tax revenue than under the Current System, and the county $5.8 million less.

While it obviously makes no sense for the county to take such a hit, there are at least two ways to address the distribution imbalance.

The simplest way is reallocation. This could be done by writing a check, altering how much the town and county pay for joint departments (e.g., START and Parks & Rec), or through a variety of other mechanisms.

Another approach is to reduce the amount of money reimbursed to taxpayers. For example, if the MOTH were structured so that taxpayers were reimbursed only 50% of a property type’s median value, the county would take in as much revenue as it currently does.

The problem with the “reduce the reimbursement” approach is that it undercuts the primary reason for implementing the MOTH. For example, by cutting the reimbursement rate from 100% of median to 50%, the number of property owners paying no-or-lower taxes would drop from 65% to 41%. That’s still a lot of people, but it makes the MOTH’s rationale less compelling.

Ultimately, allocation questions aren’t what matters. What matters is this: If the community feels the MOTH is a good idea, it would be folly to let a debate over how to distribute funds scuttle the overall concept.

Indeed, the only question that really matters is whether pursuing the MOTH is in the community’s best interests. To answer that, we first need to develop a better understanding of who we are and where we’re heading.

The Nature of the Community

What kind of community do we want?

Historically, Jackson Hole’s character has been defined by the valley’s geographic isolation. Moving here required residents to make sacrifices ranging from limiting their earning power to enjoying fewer cultural and consumer opportunities. However subliminally, that sense of shared sacrifice forged a community of folks who prioritized “place” over “big city amenities.”

Today, living in Jackson Hole requires far fewer sacrifices. Changes in the economy and improvements in technology and transportation have rendered the valley’s geographic isolation increasingly moot, allowing residents to enjoy an ever-widening range of culture, consumer goods, and other opportunities. These changes have also made it easier to connect to the world beyond the Tetons.

The reduction in challenges has produced a surge in the number of people wanting to live and invest in Jackson Hole. As that has occurred, the price of Jackson Hole’s scarcest commodity – real estate – has skyrocketed, making it harder for all but the wealthiest to afford to live here.

Which raises a fundamental question: Is this the kind of community we want? If not, then we also need to explore a second fundamental question: What is the proper role of government?

The Role of Local Government

Like any other service provider, local government’s biggest expense is its employees. And as with any employee, the biggest expense facing government employees is housing.

Add in the fact that Jackson Hole’s housing prices are rising much faster than local government’s revenues, and the result is this: Within the next few years Jackson Hole will face a reckoning. Like it or not, the community will have to choose between two options: Put substantially more money into local government coffers, or see a reduction in governmental services.

As with so many of the trends currently shaping Jackson Hole, this “Champagne tastes on a beer budget” phenomenon was occurring before the COVID pandemic. Paradoxically, even though COVID amplified a lot of the pressures on the community, for two reasons it also produced short-term budget benefits for local government:

- When COVID hit, both the town and county greatly tightened their budgets by implementing hiring freezes and cutting costs wherever possible; and

- Federal money poured in to help local governments cope with the pandemic’s challenges.

Neither of these gains were sustainable, though, so today local government finds its expenses growing faster than its revenues. More ominously, looking down the road a few years expenses will likely grow faster still.

This imbalance can’t last. So what can we do?

One option is to reduce staff. But because the pandemic taught us that asking government employees to constantly work extra hours produces burnout, reducing staff ultimately means cutting services and/or reducing service levels (e.g., plowing streets less frequently or putting fewer cops on the street).

The other option is to raise taxes. This would allow government to maintain its current breadth and depth of services, and perhaps even raise them. Critically, as staff turns over, it would also allow government to promise new employees that they, too, might live in the community they’re being hired to serve.

So we face a lousy choice: fewer services or higher taxes. Making matters more complicated still is the Jackson Hole Conundrum: As the community becomes more economically stratified, an increasing number of residents and businesses will need an increasing amount of help from a government increasingly unable to provide it.

We also can’t ignore the likelihood that, as housing prices continue to rise, people buying high-end homes will expect ever-higher levels of service from local government.

If we choose to maintain or even increase services, how will we pay for them? Until Jackson Hole can figure out a more effective way to work with the legislature, we don’t have many options.

The Essential Question

Wyoming’s tax and trust laws apply in all of the state’s 23 counties. Yet overwhelmingly, newly arrived well-to-do Wyoming residents have chosen to move to Jackson Hole. In 2020, Teton County had 4% of Wyoming’s total population, 18% of its high-end households, and 51% of its high-end income. Today, the population percentage is likely unchanged, but the high-end household and income percentages are almost certainly higher.

So why do the well-to-do want to come here? That’s a question worth exploring. And once we answer that, here’s another: Would those attracted to this place be willing to give back some of the money they’re saving in taxes to help Jackson Hole maintain its essential qualities and, more broadly, its sense of community?

For that, at its essence, is what the MOTH would do – reduce the financial stress on Jackson Hole’s land-rich, cash-poor residents by asking owners of higher-end properties to pay a larger share of government expenses.

Viewed this way, the MOTH is more than a public policy proposal. It can also serve as the catalyst for asking ourselves what we value and what we’re willing to do in support of those values. It won’t be an easy conversation, but this place and this community are well worth it.