Hello, and happy Spring (or at least Spring Break)

Tax day looms. In an effort to further my brand, I’ve gone down a rabbit hole of analyzing income tax data. You, dear reader, are the lucky beneficiary of my efforts.

In particular, I’ve been using IRS data to explore two questions: “As the cliche goes, are Jackson Hole’s billionaires driving out its millionaires?” and, if so, “How did COVID affect things?”

Three recent occurrences sparked this research.

The first was a poignant comment my son recently shared with me. Born and raised in Jackson Hole, he observed: “These days, when I hear about my hometown, it’s no longer that the Tetons are a really cool place. Instead, it’s that Jackson Hole has become a caricature of extreme wealth.”

The second was a conversation with a venture capitalist. Recently arrived in town, my new friend shared several observations about our fair community. He caught my ear by remarking that we need to construct two tunnels – one “between Jackson Hole and Idaho Falls;” the other “between Teton Village and Jackson Hole.” More comprehendibly, he noted that “if wealthy people stop liking it here, they’ll move to Montana or some other place.”

Finally, he also acknowledged that the wealth moving into Jackson Hole is causing a lot of problems, and potentially permanently damaging the community. However, “…that’s just how it goes in America.”

The third occurrence was a Wall St. Journal poll asking about five core values. The results showed steep declines in support for four traditional pillars of American life: patriotism, religion, having children, and community involvement. The only value gaining traction was money: In 1998, 31% of respondents said money was “very important;” in 2019, it was 40%; today it’s 43%.

Combined, the poll results and the two sets of comments neatly distill the concerns I’ve been hearing about the greater Tetons region – folks are increasingly worried that our sense of community is eroding, falling victim to a growing focus on that lowest of all common denominators: money.

Is that the case? Obviously IRS data can’t answer that directly, but they did allow me to conclude that, in both Jackson Hole and our peer “lifestyle communities,” the cliche has merit: the newly-arriving billionaires are metaphorically driving out the millionaires. Further, COVID did throw gasoline on that fire.

Equally interesting, the same phenomenon is happening – albeit at lower dollar figures – in not just lifestyle communities, but in “lifestyle suburbs;” i.e., the regions surrounding the lifestyle communities. There, in places like Wyoming’s Star Valley and Idaho’s Teton Valley, newly-arrived residents are making more money than longer-term residents. In turn, this new wealth seems to be pushing out those lower down on the income scale.

I think these findings are both interesting and important, especially because the influx of wealth is at the core of every challenge facing not just Jackson Hole, and not just the Tetons region, but every desirable place on Earth to live.

Further, I don’t see the underlying dynamics changing. Indeed, the data confirm my strong sense that, in desirable places around the country, socio-economic-driven changes are accelerating in both pace and magnitude. As they do, once-distinctive places are seeing their cultures become increasingly homogenized; their class structures become increasingly income-stratified. In turn, all this is wreaking havoc on the sense of community, leaving long-time residents reeling.

Below, this very lengthy newsletter shares the results of my digging. Thanks in advance for working through it, and I hope you find the information valuable.

As always, thank you for your interest and support.

Cheers!

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

Introduction

Annually, for every county in America, the IRS tallies how many households filed tax returns from the same county two years in a row, and how much total Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) those households reported. The IRS calls these “Non-Migrants.” It also reports the same information for households moving out of one county into another (In-Migrants) and vice-versa (Out-Migrants).

The analysis below looks at four geographies:

- Teton County, WY

- The Tetons region

- Wyoming

- Communities similar to Jackson Hole and, more broadly, national trends

The analysis emphasizes In-Migrant income because people with the highest incomes have the greatest freedom to live where they want to, rather than where they have to.

Teton County, Wyoming

Between 2010 and 2020, a total of 12,700 households moved into Teton County. 12,197 moved away, a net gain of 503 new households over 10 years.

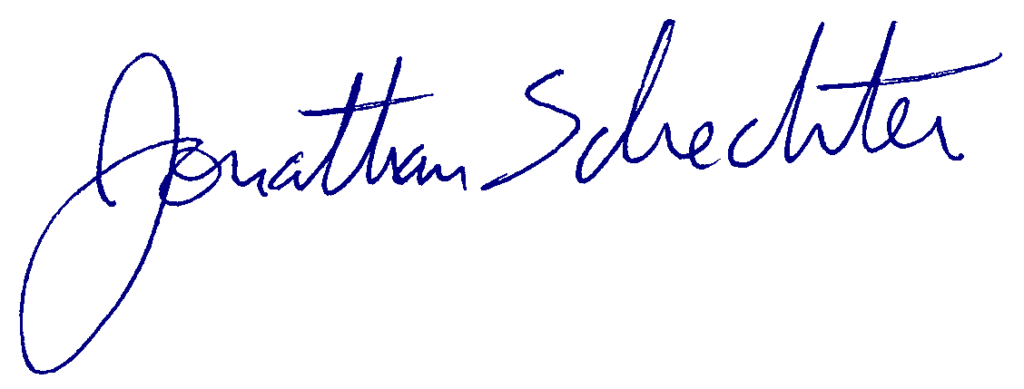

In some years, there were more In-Migrants than Out-Migrants; in other years, it was the opposite. In a typical year, 11.4% of Teton County’s households had lived elsewhere the previous year, and 10.9% moved somewhere else. The net result was a modest annual gain of 0.5%. (Figure 1)

Far less modest were the income differences.

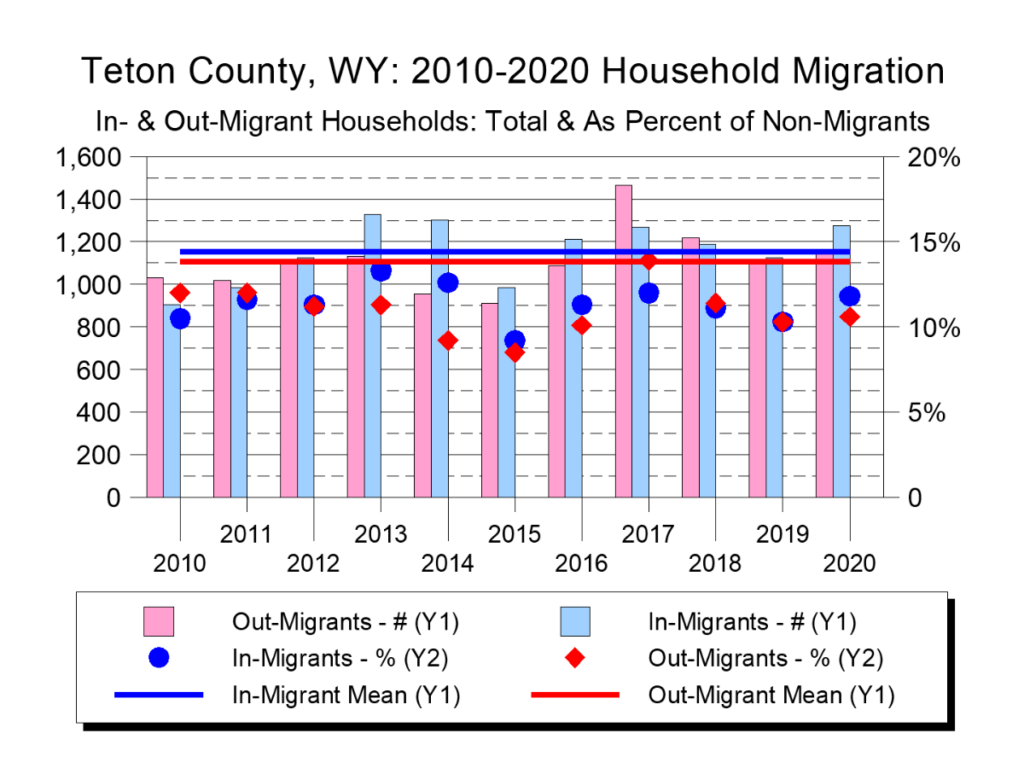

In 2010, Teton County’s 8,569 Non-Migrant households had a mean AGI of around $78,000. The 903 households moving into Teton County had a mean AGI of around $106,000 – 36% higher. The 1,032 households moving away had a mean AGI of around $42,000 – 46% lower than that of the Non-Migrants.

Over the subsequent decade, those figures varied. In most years Teton County’s Non-Migrants had a higher mean AGI than did the newcomers. The only constant was that Teton County’s Out-Migrant households always had a much lower income than did In-Migrants.

Then, in 2020 – the beginning of the COVID migration – things went crazy.

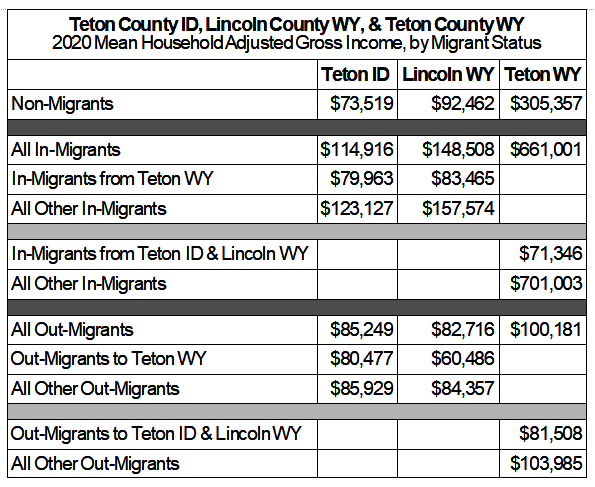

That year, Teton County’s 1,275 In-Migrant households – the highest number of In-Migrants since 2014 – had a mean AGI of $661,001, more than twice the previous In-Migrant record of $316,910. It was also over twice the mean AGI of the county’s Non-Migrants, who enjoyed a nation-leading $305,357.

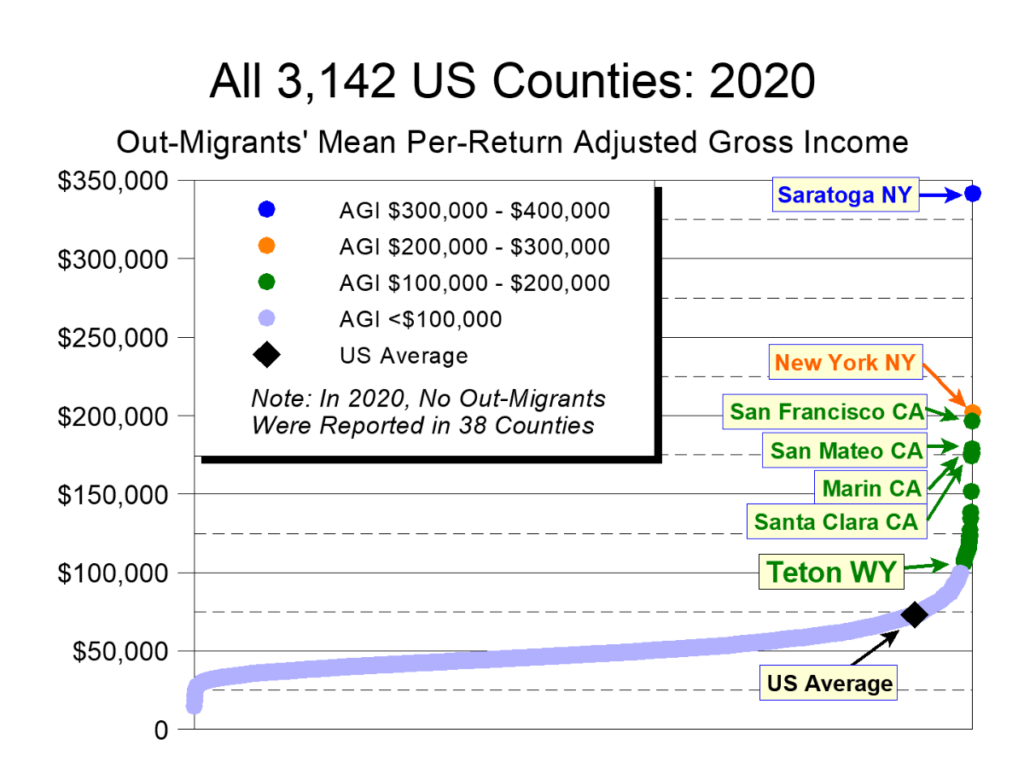

Meanwhile, those leaving the county in 2020 had a mean household AGI of $100,181 – over six times less than the In-Migrants’ income. (Figure 2)

To put the Out-Migrant figure in perspective, in 2020 the typical Teton County Out-Migrant household earned a lot of money – 15% more than the mean US AGI. Yet in a cruel coincidence, that $100,181 figure was also just 15% of the income earned by the typical In-Migrant household.

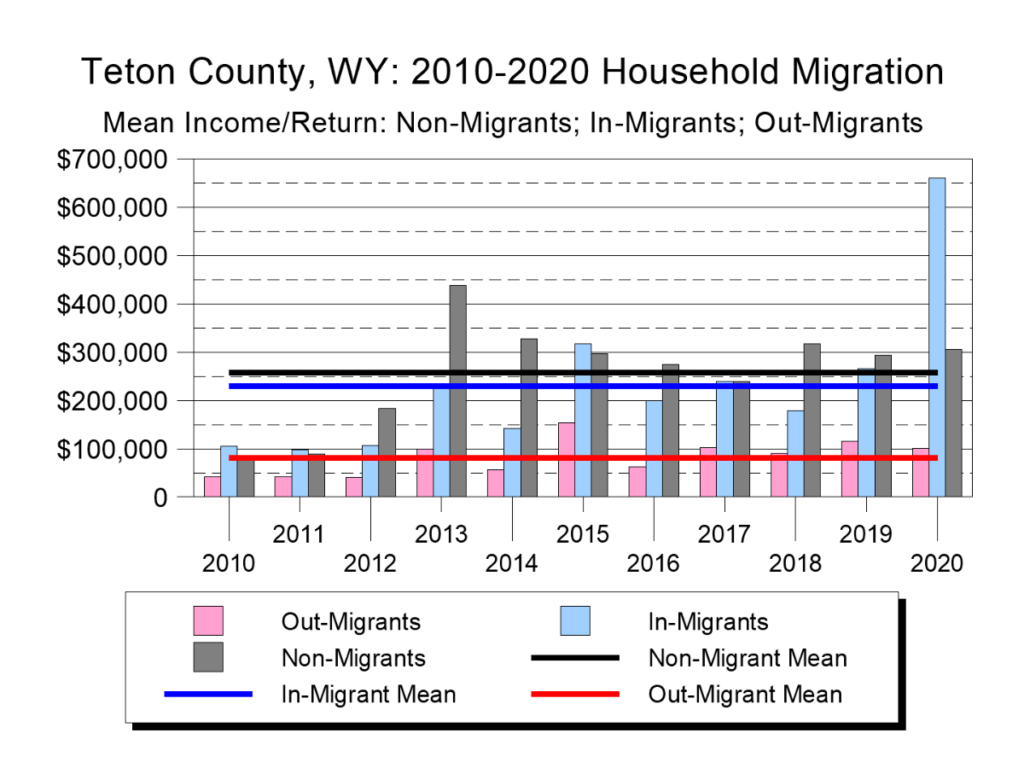

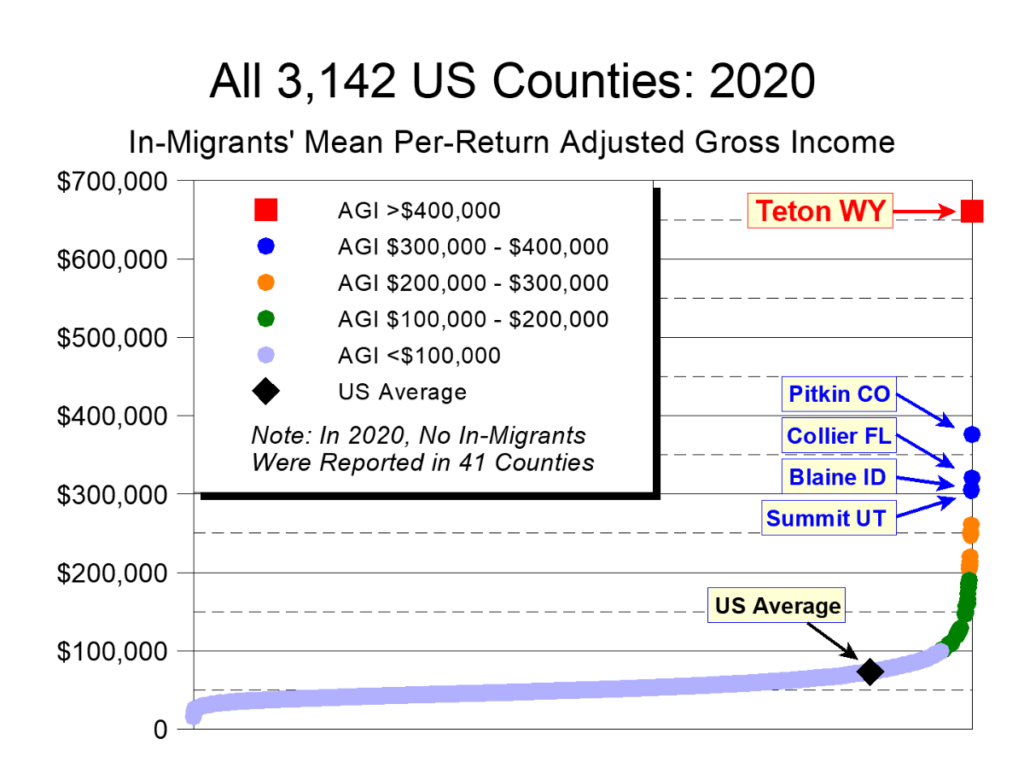

In 2020, Teton County led the nation in both mean Non-Migrant AGI and In-Migrant AGI: $305,357 and $661,001 respectively. Our Out-Migrant AGI of $100,181 ranked 49th, putting us in the top 2% of all US counties. (Figures 3, 4, and 5)

Because our In-Migrant income was so high, though, in 2020 – again, the first year of the COVID migration – In-Migrants to Teton County accounted for fully one-fifth of the county’s total income. The previous record had been one-eighth.

The bottom line? For many years, the incomes of those moving to Jackson Hole have been far greater than the incomes of those moving out. In 2020, the tidal wave of new In-Migrant money was so great that it completely overwhelmed the incomes of Jackson Hole’s Out-Migrants. Ominously, it also more-than-doubled the $305,357 made by Teton County’s Non-Migrants; i.e., the community’s locals.

Therein lies the evidence that, at least since COVID hit, Jackson Hole’s metaphorical billionaires have been displacing our metaphorical millionaires. Which begs an interesting question: Where are all those displaced millionaires going? To answer that, let’s look at regional trends.

Tetons Region

Here’s a rather astonishing statistic.

In 2020, Teton County, WY’s In-Migrants earned 20.3% of the county’s total AGI. This ranked us 5th nationally.

That same year, Teton County, ID’s In-Migrants earned 18.6% of that county’s total income, ranking it 11th nationally. In Lincoln County, WY – Jackson Hole’s other “bedroom community” – In-Migrants earned 14.5% of that county’s total income, ranking it 53rd nationally. (If it were possible to focus just on the Star Valley portion of Lincoln County, the percentage would be much higher).

In 2020, Teton County, WY’s In-Migrant mean AGI of $661,001 led the nation. That same year, Lincoln County’s typical In-Migrant household earned $148,508, ranking it 28th nationally. In Teton County, ID, the figures were $114,916 and 70th.

Where did our neighboring counties’ big-earning In-Migrants come from?

Not surprisingly, Teton County, WY accounted for the greatest number of In-Migrants to both Lincoln, WY and Teton, ID, accounting for 12% and 19% of new households respectively.

What’s interesting, though, is that those moving from Jackson Hole to Star Valley or Idaho’s Teton Valley weren’t those with the most money. Instead, those moving to Jackson Hole’s “lifestyle suburbs” from outside the Tetons region had much higher mean incomes than those moving within the region (Table 1)

Why would this happen? The data can’t answer this question directly, but I have a two-part hypothesis.

Part 1 is that younger, less well-off people priced out of Jackson Hole but wanting to stay in the region found they could afford housing in adjacent counties. Hence the lower mean incomes of those leaving Teton County, WY for our neighboring counties. These folks love our region, and are willing to do whatever they can to stay proximate to the Tetons.

Part 2 is that a number of well-to-do COVID migrants living outside our region wanted to move here, but found themselves priced out of Jackson Hole. The alternative? Move to neighboring counties.

Add it together, and two things are going on. First, Jackson Hole is pushing its less well-to-do out to surrounding communities, who in turn are pushing their less well-to-do even further afield. Second, those who can’t afford Jackson Hole in the first place are choosing to go to its lifestyle suburbs, where the newcomers make more than extant residents.

Over time, these disparities will greatly increase the economic pressures facing our region, particularly for new housing. Even if scads of new units are built, though, the mounting economic pressures are so powerful that it will make it increasingly difficult for the less well-to-do to live not just in Jackson Hole, but anywhere in the greater Tetons region.

Wyoming

Wyoming is considered to be an “on-shore, off-shore tax haven,” the state with the most wealth-friendly income tax and trust laws in the nation.

Because these laws apply in each of Wyoming’s 23 counties, if all other things are equal, people should be similarly attracted to each county.

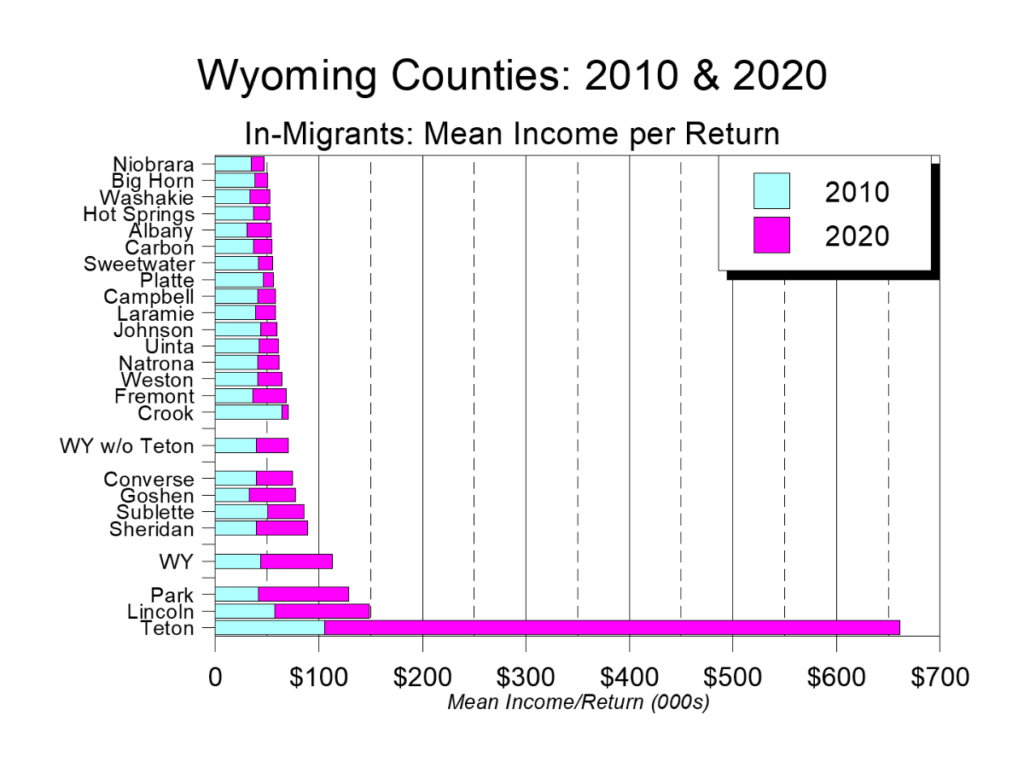

As Figure 6 illustrates, though, all other things are not equal. Not even close.

In 2010, the average Teton County In-Migrant household earned $105,850. This was highest in the state and third-highest in the nation.

That same year, Wyoming’s lowest figure was in Albany County. There, the average In-Migrant household earned $30,538, 29% that of Teton County

In 2020, the average Teton County In-Migrant household earned a nation-leading $661,001. That same year, Wyoming’s lowest figure was in Niobrara County. There, the average In-Migrant household earned $46,989, 7% that of Teton County.

Had Teton County not been part of Wyoming in 2010, the state’s mean In-Migrant AGI/household would have been 8% lower. In 2020 it would have been 38% lower.

Strikingly, in 2020 only two other counties exceeded Wyoming’s statewide mean In-Migrant AGI: Lincoln and Park. The former is a landing place for those priced out of Jackson Hole; the latter is Wyoming’s only other national park gateway county.

This suggests that more than just tax breaks is affecting where well-to-do In-Migrants settle in Wyoming. Given the counties which are attracting such folks, it appears the big differentiator is the qualities offered in the northwestern part of the state. There, in 2020, the four northwest Wyoming counties (Lincoln, Park, Sublette and Teton) accounted for 14% of Wyoming’s population, 20% of its acreage, and 30% of its AGI. They also are home to 56% of Wyoming’s US Forest Service land and 99% of its National Park Service land.

National Trends and Peer Communities

As the umbilical cord that connects where we live with where we work becomes increasingly stretched, frayed, and broken, people of means are finding it increasingly easy to live where they want to live, rather than where work requires them to live.

To that end, where are people of means moving?

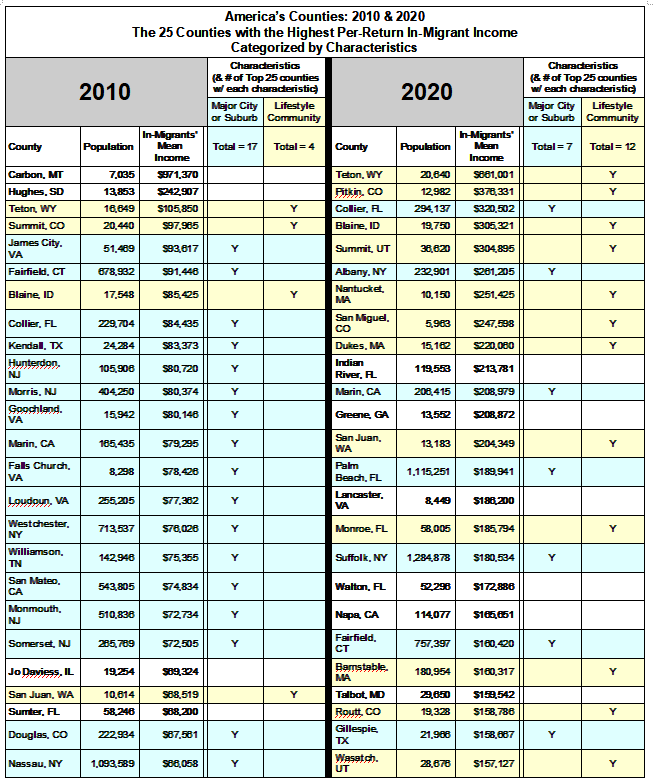

In 2010, of the 25 counties with the highest In-Migrant mean household AGI, 17 were the location of either a major city or the suburbs of a major city. Only 4 were communities where lifestyle was the main draw.

In 2020, the situation was dramatically different. Only 7 of the Top 25 counties were the location of either a major city or suburb. In contrast, 7 of the Top 10, and 12 out of the Top 25, were lifestyle communities. (Table 2)

Between 2019-2020, 23% more people moved into the Top 25 high-income lifestyle communities than moved out. What’s really striking, though, is that the typical In-Migrant household made more than twice as much as the typical Out-Migrant household: $229,927 v. $95,486. Also notable: the mean Out-Migrant AGI of $95,486 was 10% higher than the mean US household figure. This strongly suggest that while lifestyle communities’ Out-Migrants are doing very well by national standards, they are getting crushed by lifestyle community standards.

As is true with so many income metrics, in 2020 Teton County had the most extreme gap between mean In-Migrant and Out-Migrant household income – the former was the nation-leading $661,001; the latter was $100,181, a 660% difference. In second place was Pitkin CO, where the difference was “only” 460%.

Also of note is that, among America’s 3,142 counties, Park County, WY ranked 19th in its gap between In-Migrant and Out-Migrant incomes (230%); Lincoln County, WY ranked 57th (180%), and Sheridan County, WY ranked 219th (146%). Even Teton County, ID (135%) ranked in the top 12% of all US counties – in 2020, the typical Teton Valley In-Migrant household made $114,916, while the typical Out-Migrant household made $85,249.

The conclusion? As the work-home umbilical cord becomes increasingly tenuous, people are flocking to places offering a high quality of life. For those who can afford it, lifestyle communities are all the rage. For the less well-to-do, lifestyle suburbs are becoming increasingly attractive. As all this plays out, though, those on the bottom end of the income scale are finding it increasingly difficult to stay in places which, a generation ago, were much more affordable.

Ominously, because those lower-income folks are often the workers undergirding the “lifestyle” in lifestyle communities, the traditional tourism business model – which depends on large numbers of relatively low-paid employees – likely faces a period of wrenching adjustment.

Observations

So what to make of all this?

Three meta-observations leap out:

- It’s not just Jackson Hole

- Going forward, current trends will accelerate

- Current approaches are no match for current patterns

It’s Not Just Jackson Hole

The fact that billionaires seem to be metaphorically pricing out millionaires in every desirable place is a modern-day variation of an age-old theme.

Humans have constantly searched for a better life. In America, 19th century settlers migrated west. In the 20th century, city-dwellers flocked to the suburbs. In the 21st century, our nation and planet are experiencing virtual suburbanization.

Whether physical or virtual, suburbanization has been made possible by improvements in technology and transportation, as well as changes in the economy and mores. In the 20th century, the ever-stretching umbilical cord between work and home was limited by physical constraints such as highways and telephone lines. As those extended their reach, so too did the suburbs.

In this century, technology has rendered moot most physical constraints – the rapid spread of reliable wi-fi is allowing increasing numbers of people to live where they want to live, regardless of their profession.

The people best-positioned to take advantage of this phenomenon are the well-to-do, whose sources of income are increasingly disconnected from where they live. As folks earning location-neutral income flock to places once considered off the beaten path, the newcomers’ wealth is making it increasingly challenging for long-term residents of formerly-remote places to continue to afford to live there.

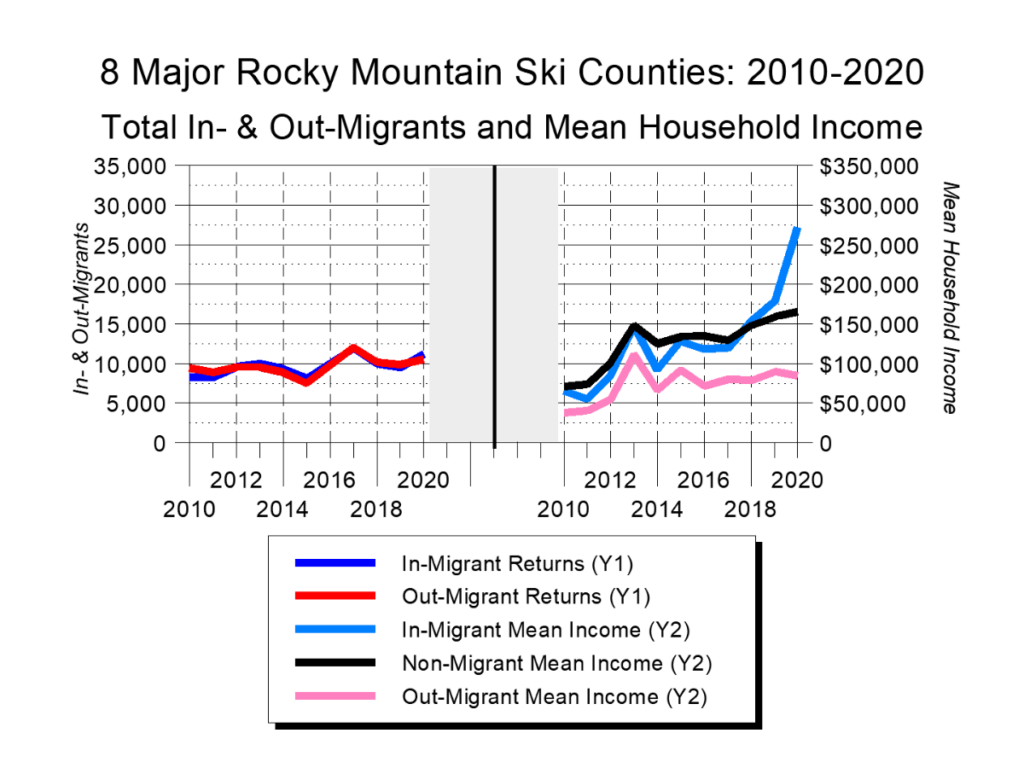

This phenomenon is most easily seen in major resort communities. As Figure 7 shows, over the past ten years, the eight major Rocky Mountain ski counties – Teton WY (Jackson Hole), Blaine ID (Sun Valley), Summit UT (Park City), and Eagle, Pitkin, Routt, San Miguel, and Summit CO (Vail, Aspen, Steamboat, Telluride, and Breckenridge respectively) – saw virtually identical numbers of In- and Out-Migrants.

What’s striking, though, is that starting in 2018, the income earned by the typical In-Migrant household not only started growing faster than the typical Out-Migrant household, it also started growing faster than the typical Non-Migrant household.

That this phenomenon started a couple of years before COVID is significant, for it strengthens the argument that COVID merely accelerated extant trends.

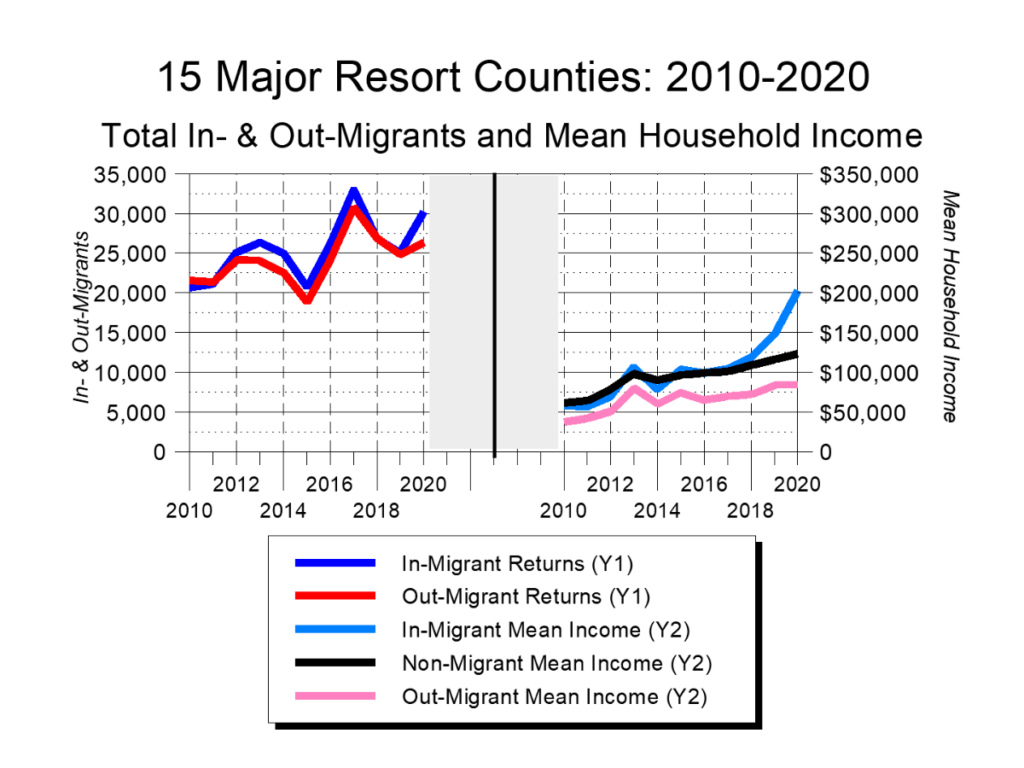

If we widen our gaze to include seven additional lifestyle-oriented counties, the same basic patterns hold true. Figure 8 adds into Figure 7 the resort counties of Gunnison CO (Crested Butte), Gallatin MT (Big Sky), Monroe FL (Key West), San Juan WA (San Juan islands) and Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket MA (Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket respectively).

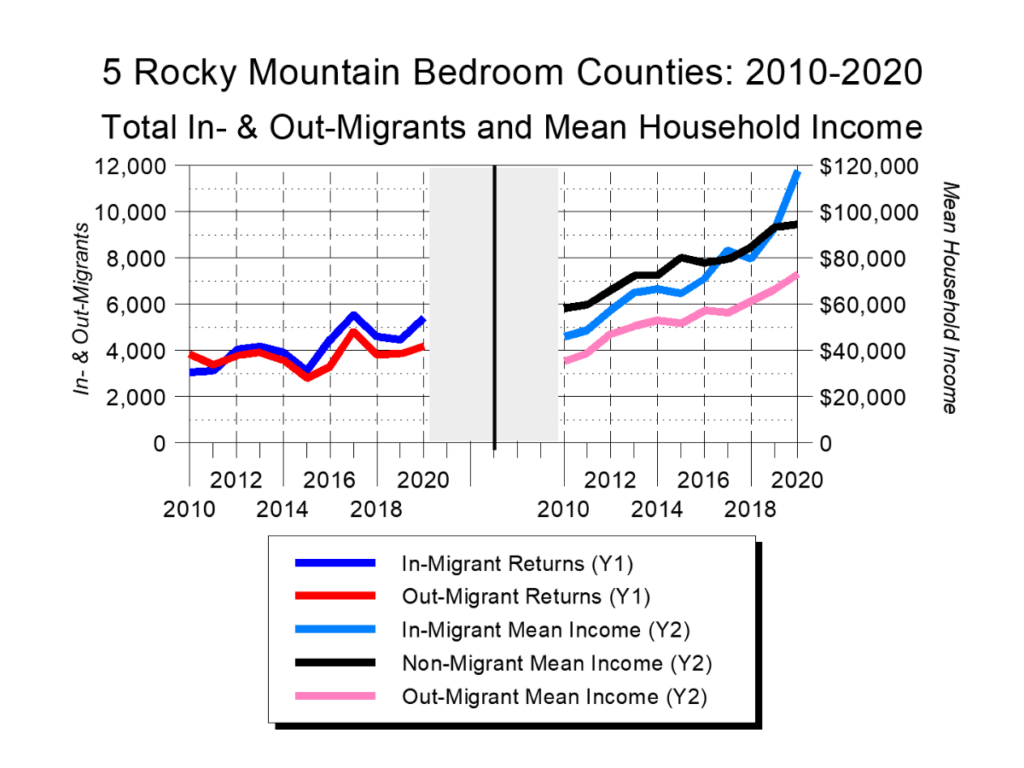

The most striking thing of all, though, is that the same basic phenomenon is also occurring in the bedroom counties adjacent to major ski counties. Figure 9 looks at five counties where people priced out of major ski counties are moving: Garfield and Ouray, CO (proximate to Aspen and Telluride respectively), Wasatch UT (over the hill from Park City), and Teton ID and Lincoln WY (Jackson Hole’s neighbors).

While these lifestyle suburbs have much lower incomes, they share with their lifestyle community neighbors the fact that lower-income residents are being priced out. Combine this with the growing incomes of the lifestyle suburbs’ Out-Migrants, and it suggests growing numbers of people may be finding themselves priced out of not just lifestyle communities, but entire “lifestyle regions.”

Also striking is that in these lifestyle suburbs, the number of In-Migrants began consistently exceeding the number of Out-Migrants in 2016. This suggests lower-income residents of lifestyle communities began feeling serious economic pressures several years ago, catalyzing what has become a steady exodus to the surrounding lifestyle suburbs.

The ultimate consequence of this pricing-out phenomenon is what I call “special challenges;” i.e., the challenges facing all special places to live (and increasingly their physical suburbs). This suite of challenges is hallmarked by affordable housing, transportation, and growing income inequality, issues which haven’t been successfully addressed anywhere, even in big cities with a lot more money. For lifestyle communities – with their much higher incomes (and therefore much higher housing prices) and much smaller budgets – the challenges are even greater.

Going Forward, Current Trends Will Accelerate

As my venture capitalist friend noted, wealthy people go where they want to go. As they do, their actions create ripple effects in not just the communities they move to, but entire regions.

Decades ago, the quest for a better life led people without much money to geographically isolated places. In Jackson Hole, the original In-Migrants were ranchers; later came the wave of recreational enthusiasts. Similar patterns took place throughout the western US.

Bonding together previous generations of In-Migrants was a shared sense of sacrifice. By moving to a remote place, they enjoyed certain qualities of life available only in small towns in remote regions. But those qualities were not cost-free. Instead, they required In-Migrants to give up things ranging from proximity to friends and family to the employment, cultural, commercial, and educational opportunities available only in larger areas.

Today, moving to lifestyle communities such as those in Table 2’s Top 25 requires increasingly fewer sacrifices, particularly for the well-to-do. As a result, more and more people are making an increasingly easy choice – like generations before them, they’re heading to places offering a higher quality of life. As this “no trade-offs” pattern continues, so too will the income growth in lifestyle communities, with its concomitant effects on both those communities and their surrounding regions.

Current Approaches Are No Match for Current Trends

My analysis makes it clear where things are going – towards a future where Jackson Hole and, more broadly, all nice places to live are increasingly hallmarked by cultural homogeneity and economic stratification.

Knowing this, do we like where we’re heading? If we don’t, are we are willing to do the hard work necessary to create – or, more precisely, potentially create – an alternative future?

When running for re-election last fall, hundreds of people shared with me their concerns about where Jackson Hole is heading. Many harbored a much more personal concern – whether they will be able to remain in the community.

In times of stress, people look to government in general, and elected officials in particular, to do something. For me, this analysis is part of my response – before I feel comfortable taking action, I need to deeply understand the issue at hand.

Bigger picture, though, four years in office have made it clear to me that the forces sweeping over Jackson Hole, the Tetons region, and similar lifestyle areas are so powerful – the money is so large, and is moving with such velocity and strength – that local government can’t adequately address them.

Can local government slow things down a bit? Tweak things around the margins? Sure. But given all that’s affecting Jackson Hole, can it make a meaningful difference? No, not on its own.

Working in conjunction with other efforts, and asked to do things it can actually do, government has a vital role to play. But asking government to take the lead in producing a significantly different future is like asking a dog to climb a tree – however much it might want to, doing so is beyond its ability.

So what’s the alternative? Since November’s elections, that’s the question I’ve been asking myself. The vexing thing is that it’s uncharted territory – no place has successfully addressed its “special challenges.” Nor, with the exception of contemporary Jackson Hole, has any place in history developed a successful industrial or post-industrial economy without fundamentally compromising the health of its ecosystem.

So what do we do? For those who don’t like where things are going, how do we proceed into this uncharted territory? How do we figure out an alternative route without a map to guide us?

I don’t have the answers but over the past few months, a picture has started to emerge.

For starters, it involves gathering together and – critically – organizing the legion of folks who don’t like where things are going and want to create a different future.

To do that requires developing an alternative vision, one grounded not in platitudes but in clarity: clearly articulated values, clearly defined goals, and clear metrics for judging progress.

It also means broadening our perspectives. Dwight Eisenhower once noted “If a problem cannot be solved, enlarge it.” To me, at a minimum this means taking a regional approach to problems that transcend arbitrary political boundaries.

Finally, it also means taking a clear-eyed look at where things are, where we want them to be, and how we might get there. Then, of course, acting accordingly.

As I’m coming to see it, trying to bring all this about is emerging as the next chapter of my professional life. How to proceed isn’t clear, and how it will play out is beyond me. What I do know, though, is that I’ll need all the help I can get. Please let me know if you’d like to take part.