Hello, and Happy May!

In an interesting metaphor for life in general, and the importance of optimism in particular, my daffodils are winning their battle with spring’s snows. They’re a little worse for the wear but beautiful nonetheless.

Speaking of spring, mine has been one of polar opposites. My late March and early April were pretty quiet, especially since I spent my spring break in COVID lockdown. I emerged healthy, but somehow doing laps between my bedroom, office, and kitchen didn’t recharge me like a full-blown vacation would have. As a result, I’ve felt rather buffeted by the onslaught of issues that has recently crashed down upon Jackson and its town council.

In no particular order, these issues include:

- Notices informing property owners of a massive increase in the assessed valuation of the county’s property (the average 2021 to 2022 increase was 40%; my house went up 58%).

- Some massive cost overruns on new government buildings (building prices have gone up about 1/3 since these projects were approved three years ago).

- 18 different applications for government and non-profit capital projects seeking taxpayer funding. The collective cost of these projects is $400 million, and they’re looking for $275 million in tax revenues. Around $120 million will be available.

- The town’s new fiscal year starts on July 1, so we are trying to create a budget that, ironically, will be very tight despite record-high revenues and savings (the tightness is a function of how much the local housing and labor markets have been upended by COVID migration and related phenomena).

- A yet-to-be-finished sustainable tourism study which has both tourism’s champions and critics on edge.

- A shifting regulatory regime which is raising questions about whether local government can continue the “parklets” program that has so benefitted local restaurants the past two years.

- A real estate market increasingly disconnected from anything resembling local financial realities.

Oh, and by the way, we’re going into election season, with all its attendant silliness and angst.

Bottom line – life is rich.

I mention all this because, as I see it, it’s vital for elected officials to at least acknowledge how much angst is out there right now. To that end, in this newsletter I’d like to take a closer look at the aforementioned property valuation wallop.

With luck, in this newsletter I can shed a little light on the realities of the situation facing our community, as well as offer a suggestion to which I’d love your reactions.

- A Bit of Background

- Teton County’s Coal

- Building Trends

- Values Go Boom

- A Mill Levy Primer

- Setting Mill Levies

- Property Taxes & Local Government Funding

- Government’s Role

- Lowering Property Taxes

- 21st Century Community With a 20th Century Operating System

- Cutting the Gordian Knot

Even by my standards, this is a long newsletter. Thanks for slogging through it, and I hope you find it of value.

As always, thank you for your interest and support.

Cheers!

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

A Bit of Background

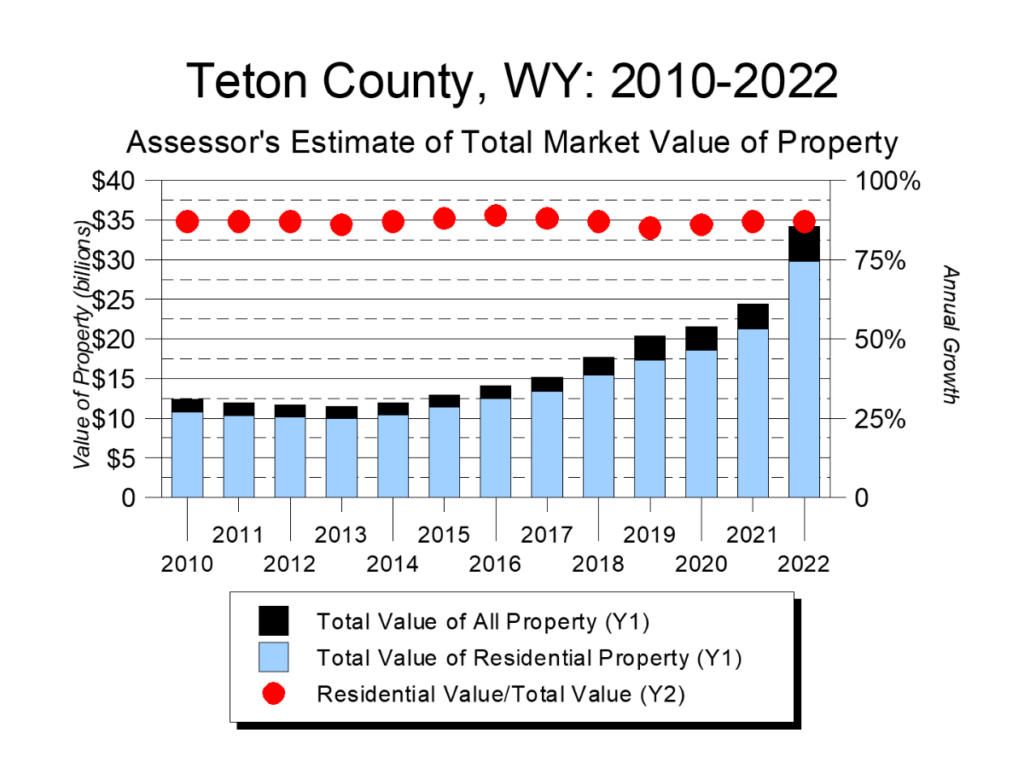

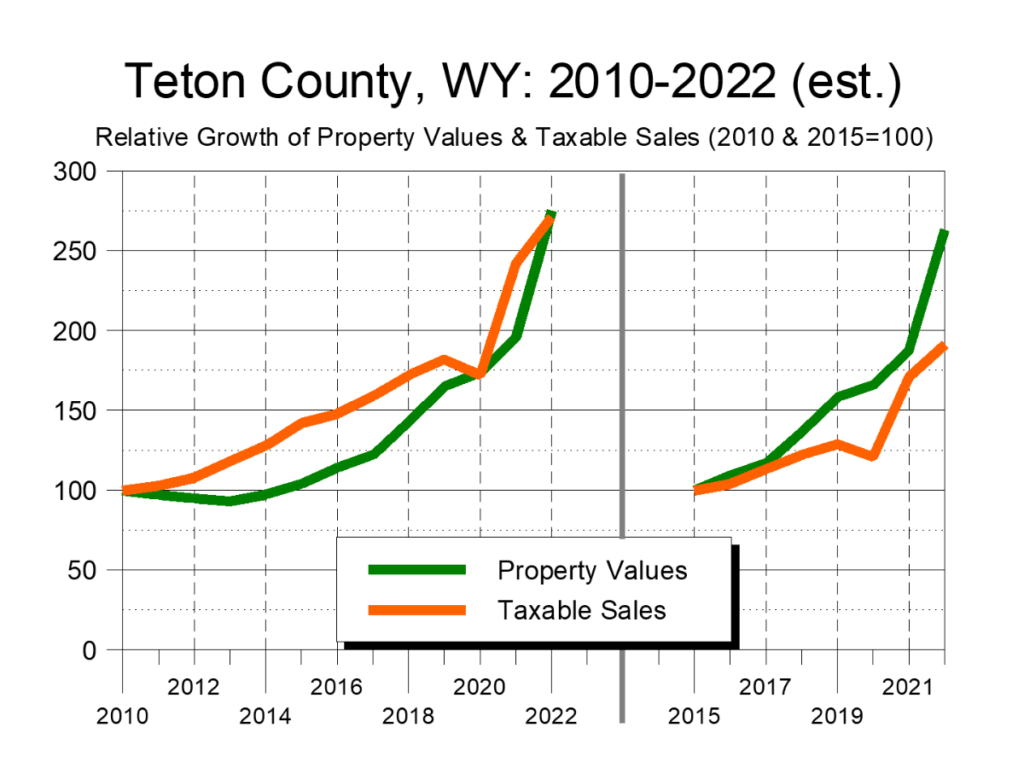

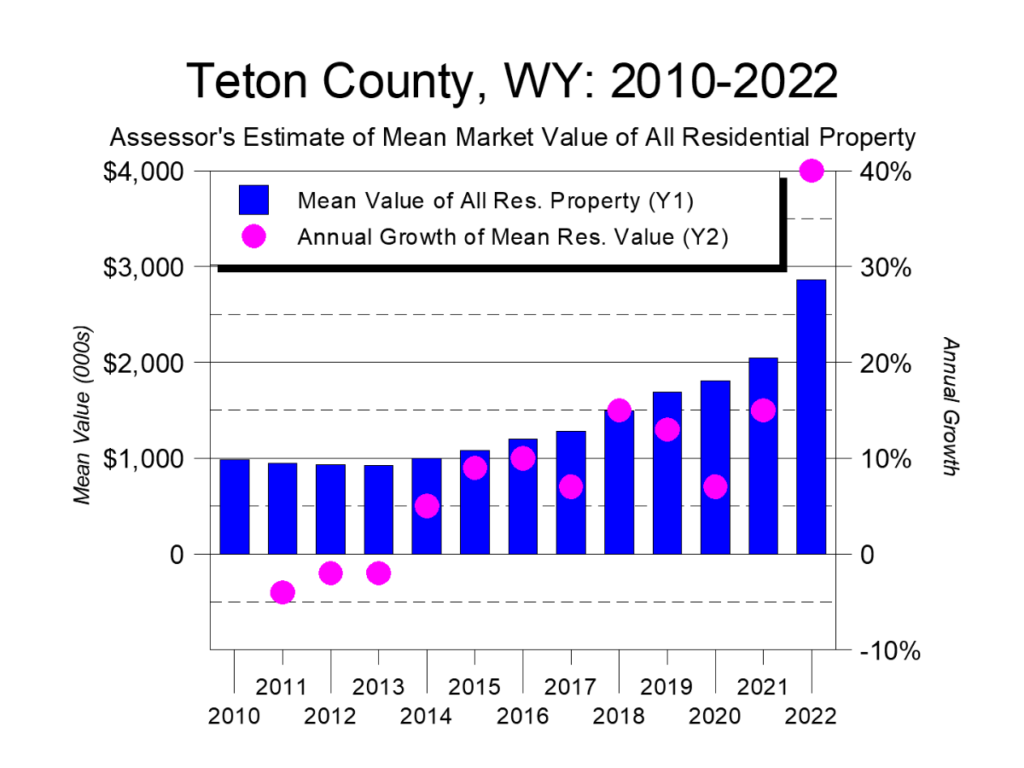

In 2010, Teton County’s Assessor estimated the market value of all property in Teton County – land, buildings, capital equipment, and personal property – to be $12.5 billion. Five years later, it was about the same – due to the recession, the total property value was $13.1 billion, an average annual growth rate of only 1%.

As a point of comparison, during the same 2010-2015 period, Teton County’s total taxable sales grew 7% annually.

Leap ahead five years, and between 2015-2020, the assessor’s estimated market value of all Teton County property grew from $13.1 billion to $21.7 billion, an average annual growth rate of 11% – 11 times greater than during the first half of the decade.

Again as a point of comparison, during that same five year stretch, total taxable sales grew 4% annually, roughly half the 2010-2015 rate.

Then we come to the past two years.

According to the figures released by Teton County’s Assessor a few weeks ago, between 2020-2022 the total market value of all Teton County property grew from $21.7 billion to $34.4 billion, an annual growth rate of 26%. Total taxable sales are growing at essentially the same stratospheric rate, which yields a doubling time of three years.

To state the obvious, no system is well-equipped to deal with such rapid growth. As a result, Jackson Hole is feeling extraordinary strain.

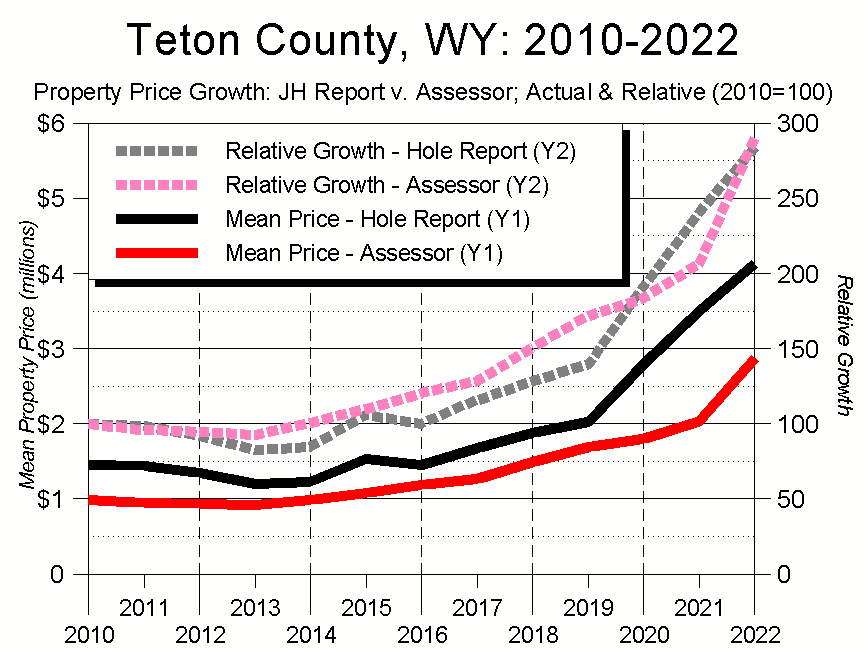

Much of the growth in property values was due to rapidly-escalating real estate sales prices. Another and unknowable portion was due to the fact that, for many years (if not decades), Teton County had been out of compliance with a Wyoming law that requires county assessors to value property within 5% of its market value. Because Teton County’s assessments had generally been way below that target range, it fell to the previous and current Teton County Assessors – Andy Cavallaro and Melissa Shinkle respectively – to bring the estimates of Teton County’s property values to where they needed to be.

Combine this legally-required adjustment with a doubling of real estate prices over the past three years, and you get a community reeling from the recent massive increase in assessed property values.

Teton County’s Coal

For over a decade, residential land – undeveloped lots, developed lots, and the buildings upon them – has accounted for roughly seven-eighths of the total value of all Teton County property.

Residential land is to Jackson Hole what hydrocarbons are to the rest of Wyoming – the foundation of the community’s property values. Unlike hydrocarbons, however, as long as the community doesn’t fundamentally screw itself up, residential land can be “mined” over and over again.

In Wyoming, property taxes are the primary source of school funding. In Teton County, residential property has become so valuable that the local school district is one of only four statewide that take in more property tax revenue than Wyoming’s funding formula says they need (one of the other districts is in natural gas-rich Converse County; the other two are in natural gas-rich Sublette County).

Until around a decade ago, Teton County’s schools cost more to run than the community generated in property taxes. As a result, Teton County was taking in “excess” property tax revenues from Wyoming’s hydrocarbon-rich counties, especially Campbell County, America’s leading coal producer. Today, with “King Coal” on the decline, Campbell County is struggling, and its schools are getting money from Teton County.

Building Trends

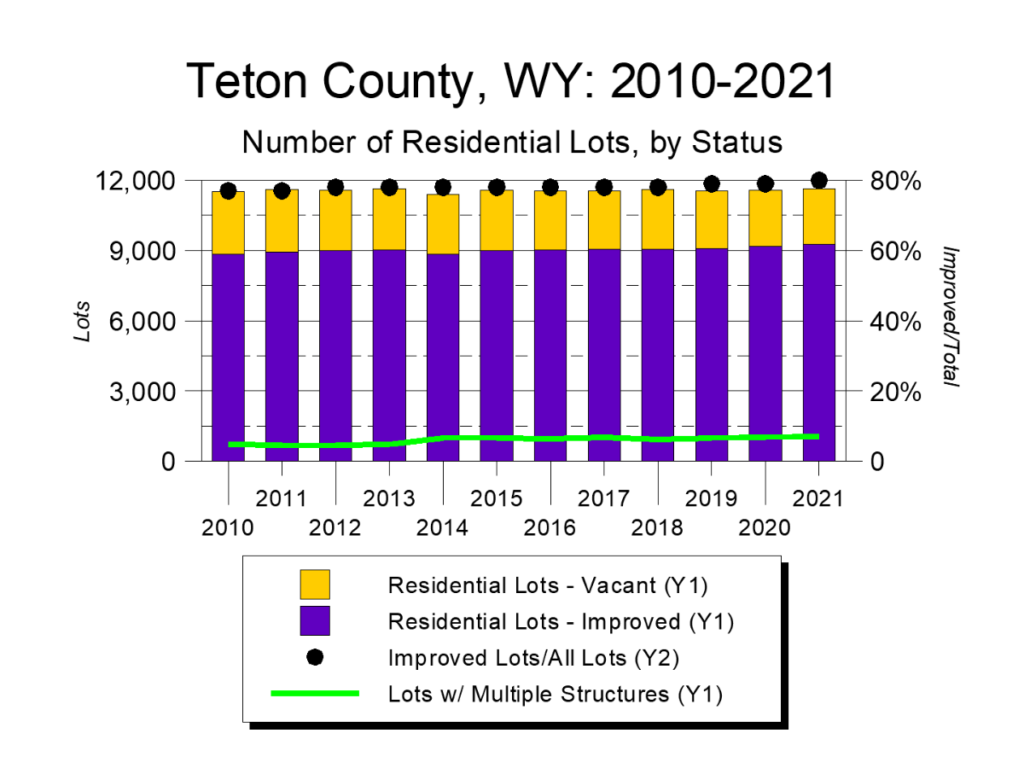

In 2010, Teton County’s Assessor identified 11,513 residential lots. 77% were built upon, and 8% had guest houses, Accessory Residential Units, or similar structures.

In 2021, there were 11,644 residential lots, an increase of 131 (1% over the 11 years). 80% were built upon, and 11% had multiple structures.

In short, between 2010-2021 Teton County added 131 new residential lots. Because it built on 448 lots, though, the inventory of empty lots declined by 317 (11%).

Over the past decade, around 30% of the new builds included a second residential structure on the property. As a result, today around 50% more properties have a second residential unit on them than was true in 2010.

The data don’t make clear how – if at all – the additional structures are being used. As a result, some may be vacant guest homes, while others could be rental properties.

Values Go Boom

As noted above, the rise in Teton County’s assessed property values has been due to a combination of rapidly rising sales prices and the assessor bringing the county into compliance with state law.

Because the assessor’s values always trail market conditions, two points are notable.

First, even though the growth in property values was shockingly high, from a percentage perspective it made sense. This is because the big jump in values brought the percentage growth of Teton County’s assessed values into line with the percentage growth of local real estate prices – both have essentially tripled since 2010.

Second, because market prices are continuing to rise, and because market prices are still much higher than assessed values, further assessed valuation increases are likely.

A Mill Levy Primer

Why do we care about assessed valuation? Because it forms the basis of property taxes.

Getting from the former to the latter involves four steps:

- Determine a property’s market value.

- Multiply it by the state-mandated 9.5% to determine its assessed value. (E.g., the assessed value of a $1 million property is 9.5% of $1,000,000, or $95,000.)

- Divide the property’s assessed value by 1,000 to determine how much it will have to pay for each mill of property tax levied (in this case, $95,000/1,000 = $95)

- Multiply the value of the property’s mill by the number of mills being levied, and the result is the property tax.

- For example, in 2021, Teton County’s base mill levy was 56.979 mills. For our $1 million home, that mill levy will result in a property tax bill of $95 x 56.979 = $5,413.

Under Wyoming law, property taxes can fund six types of governmental activities:

- Public education

- County government

- Town government

- Hospitals

- Local conservation districts

- Local weed and pest districts

Also under Wyoming law, all of these save Weed & Pest districts are directly accountable to voters by dint of their boards being publicly elected (Weed & Pest board members are appointed by county commissions).

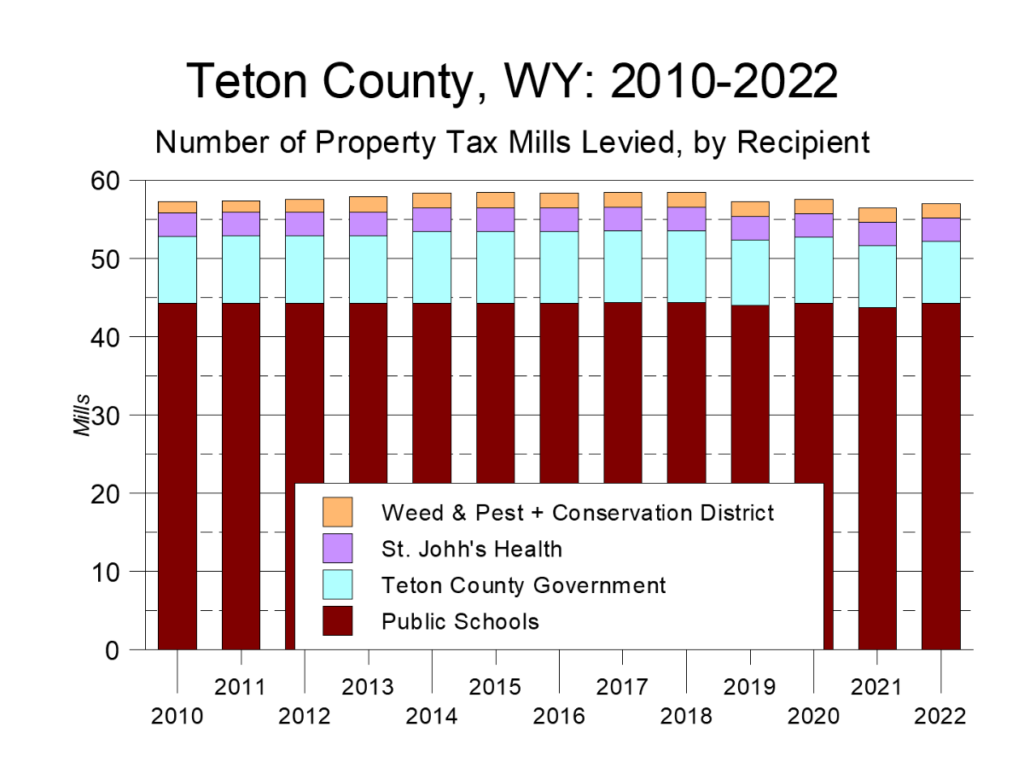

Of note is how consistent the number of mills levied on Teton County properties has stayed over the past decade-plus. The minimum was 56.479 mills in 2020; the maximum was 58.454 in 2014, 2016, and 2017 – a range of just 1.975 mills, or 4%.

Setting Mill Levies

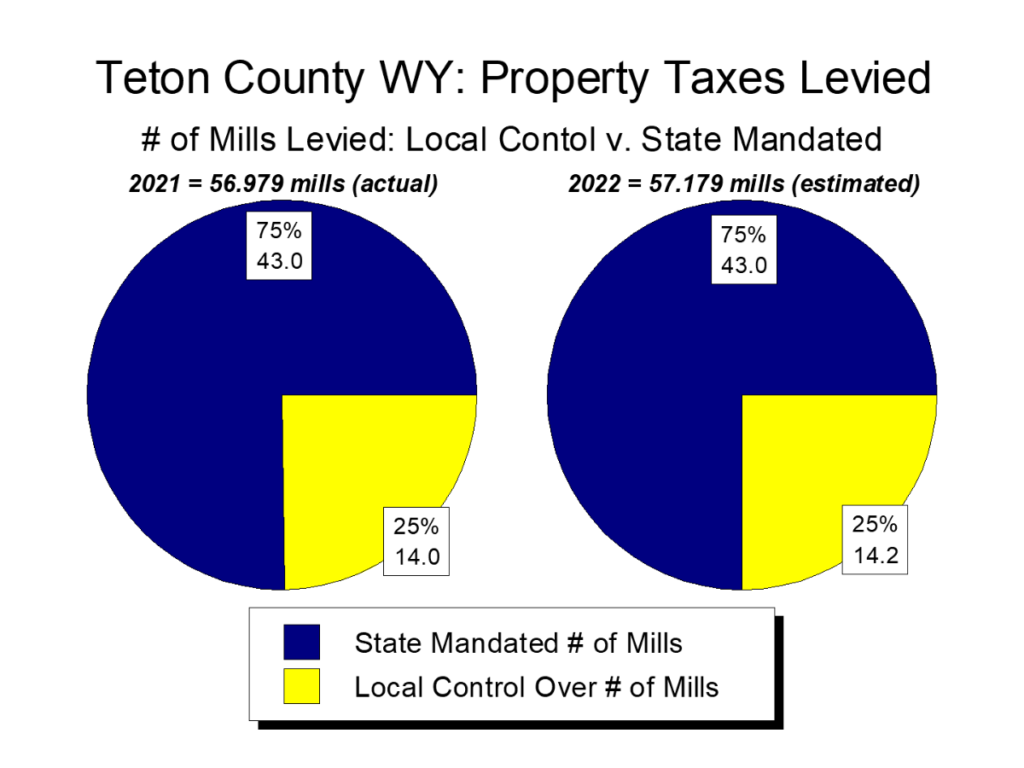

Regardless of type or location, every Teton County property is charged the same basic mill levy. 2021’s basic levy was 56.979 mills.

On top of this, some properties lie in special districts which can charge additional levies for infrastructure and the like. Examples include the Alta Solid Waste District, the Teton Village Fire, Water and Sewer district, and roughly two dozen other infrastructure and water & sewer districts.

Local government has no control over 43 (75%) of the county’s basic 56.979 mill levy. These 43 mills are mandated by the State of Wyoming, and fund the state’s public education system. Changing these rates would require changing state law or Wyoming’s constitution.

The remaining mill levies are set at rates determined by local government. In 2021, 7.879 of the additional 13.979 mills (14% of the total mill levy) were levied by Teton County to fund its operations (including fire protection, the library, and the county fair), 3 mills (5%) by St. John’s Health, and 1.8 mills (3%) by the combination of Teton County Conservation District and Teton County Weed & Pest.

Beyond the state-mandated 43 mills for education, the Teton County School Board can levy a few additional mills for specific local educational needs. In 2021, they levied 1.3 mills for this purpose, 2% of the entire assessment.

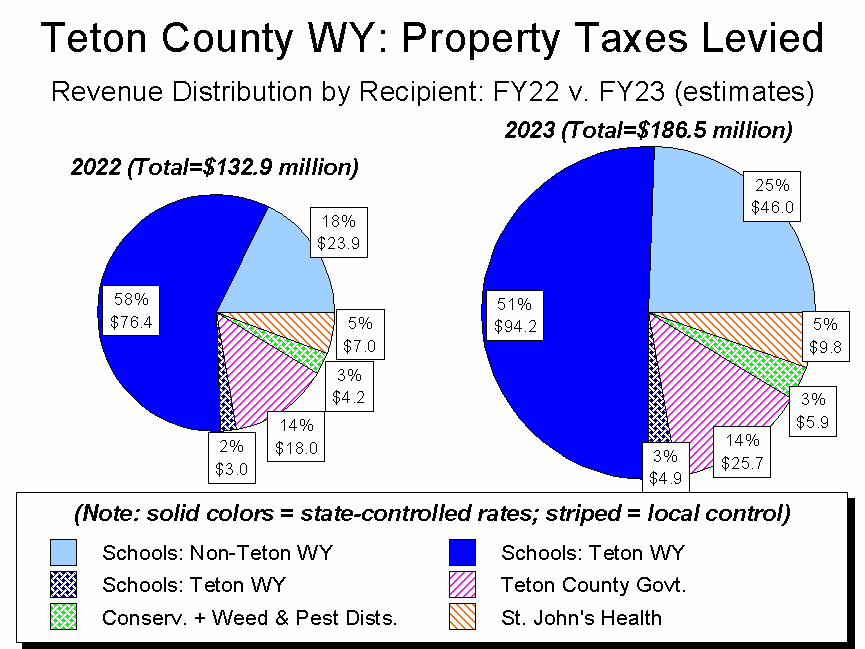

Of particular note is how much property tax goes to fund schools.

Wyoming funds its schools based on a school enrollment-driven formula. In those districts where the 43 mills of mandated property tax generate less money than the formula says they need, the state gives them extra funding. In those districts where the 43 mills generate more, the state “recaptures” the extra funds and distributes them to those districts needing money.

Because Teton County’s property values increased so much between 2021 and 2022, in FY 2023 the state-mandated 43 mills will generate around $46 million more than the state feels Teton County needs to run its schools. As a result, $46 million in Teton County-generated property taxes will fund schools in other parts of Wyoming.

To put that figure in perspective, the $46 million in property tax revenue that will leave Teton County to fund schools elsewhere in Wyoming is about the same as the combined amount of property tax revenue that will be received by all local government entities able to set their own mill levy rates: St. John’s Health, the Teton County Commission, the Teton County Conservation District, the Teton County School Board, and Teton County Weed & Pest (whose rate is set by the county commission).

Property Taxes & Local Government Funding

Because Wyoming doesn’t have a state income tax, funding for state and local governments basically rests on a three-legged stool of property taxes, sales taxes, and taxes on mineral extraction.

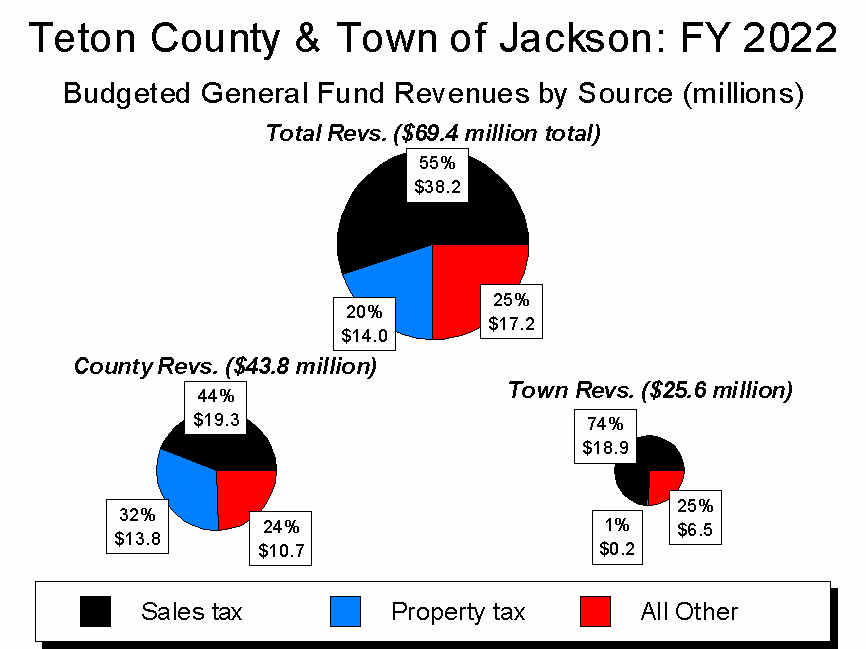

Because Jackson Hole has no economically valuable minerals to speak of, most of the funding for Jackson Hole’s local governments comes from a combination of sales and property taxes. More precisely, most of the Town of Jackson’s funding comes from sales taxes, while a goodly chunk of Teton County’s funding comes from property taxes.

Two points are noteworthy here.

First, nearly 80% of Teton County’s property value lies in the unincorporated county. As a result, every mill of property tax the county levies yields roughly 5 times more than every mill levied by the town.

In addition, under Wyoming law counties can levy up to 12 mills, while towns are capped at 8 mills. As a result, if both governments maximized their respective mill levies, Teton County would raise around 7.5 times more property tax revenue than would the Town of Jackson.

In reality, the disparity is much greater. The reason for this is the second noteworthy point.

In the 1970s, the mayor of Jackson was Ralph Gill, one of the county’s largest landowners.Worried about the town’s finances, he struck a deal with town residents: If you vote to raise the sales tax, the town will no longer levy a property tax.

In those days, Jackson was a relatively poor town with a growing tourism economy. Recognizing that, Mayor Gill argued that swapping the town’s property tax for a sales tax made sense for two reasons: because a sales tax would generate a lot more revenue than a property tax, and because a goodly amount of that extra revenue would be paid by tourists (i.e., non-locals).

Agreeing with that logic, the town’s voters approved the sales tax, and for nearly 50 years the Town of Jackson did not levy a property tax. This changed in 2021, when the town council authorized a ½ mill tax on town property. In FY 2022, this will generate around $250,000, all of which will be earmarked for Fire/EMS services. It also puts town property owners on an even footing with county property owners, for due to an anomaly in Wyoming law, county taxpayers had been paying ½ mill more for Fire/EMS than had town taxpayers.

Government’s Role

Of the discretionary mills levied by Teton County’s various taxing authorities, the largest amount is levied by the Teton County Commission. If the commissioners levy the same 7.379 mills in FY 2023 that they did this year, they will raise around $25.7 million.

What does all that money buy? The simplest answer is that it funds the basic services of county government. These Core Services range from plowing roads to running the library; from providing public health services to running elections.

In addition, property tax revenue helps fund affordable housing efforts and local human services non-profits, organizations providing services the community needs but which are beyond the scope of local government.

All of this is good stuff. Yet for completely understandable reasons, at the moment residents are furious with their government.

Why? Well, for starters, having property values jump 40% in one year is nearly inconceivable, especially in a state that prides itself on low taxes. Plus, at the same time this explosion in assessed values hit, the town council and county commission voted to pay for a 50%+ cost overrun on the expansion of the Rec Center, the mind-boggling result of scope creep, bad estimating, and construction inflation.

(Self-serving interjection. I voted against paying for the Rec Center overrun, saying I would oppose it until we were able to do two things:

- conduct a post-mortem on what went wrong; and

- understand the Rec Center cost overrun in the context of both the town’s overall budget and several other current projects also facing cost overruns.

Unfortunately there seems to be a systemic problem with the way the community handles capital projects. This is causing me great concern in general, and tremendous concern given the $290 million of new capital project proposals that just landed on our desks.)

Throw all this into an environment overwhelmed by two years of COVID-driven angst – when so much has seemed so surreal and so many of us are feeling emotionally, physically, and spiritually ground down – and the result is a whole lot of frustration and anger.

Which we electeds are hearing about. It doesn’t matter that government has no control over many of the forces washing over the community. Nor does it matter that, in many cases, there is little we can do about those forces or their consequences.

What does matter is something much more primal and much more important: In times of crisis, people look to their institutions to fix things. In in the minds of at least a very vocal minority, Jackson Hole’s local governments are currently and manifestly not fulfilling that role.

Lowering Property Taxes

So given current circumstances, what should government do?

There are those demanding that property tax rates be lowered. If that happened, who would do it and what would it mean?

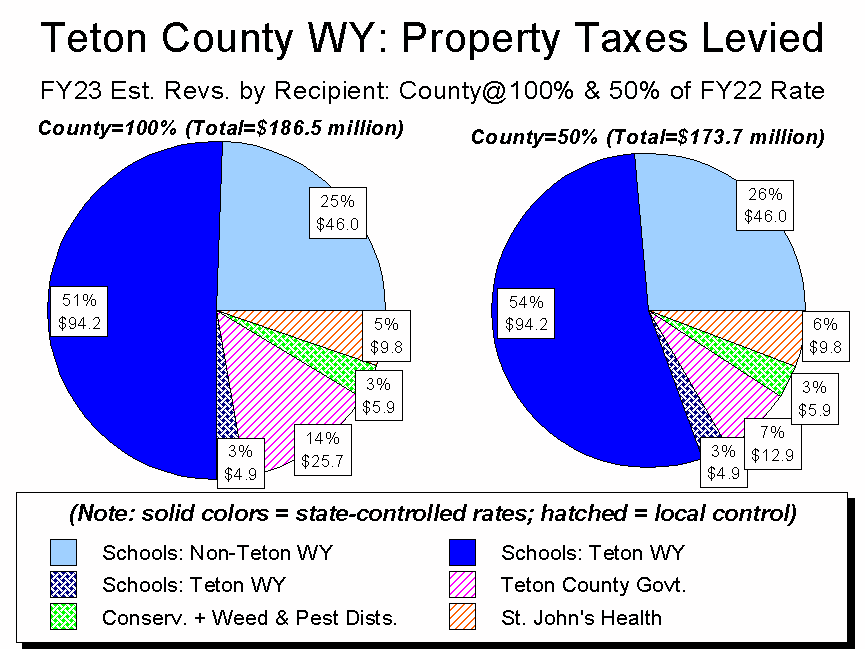

Given the fact that 75% of our property tax rate is set by the state, the only entity able to move the needle much on tax rates is the county commission. What if they were to, say, halve their mill levy?

Factually, it would cut the county’s projected FY 2023 revenues by $12.9 million, around one-sixth of their anticipated revenues. If that happened, the commissioners would face some difficult choices regarding which services to cut. Why? Because under Wyoming law, the county is legally required to provide a variety of Core Services. As a result, if major cuts needed to be made, they would likely come at the expense of non-Core expenditures such as support for affordable housing programs and the non-profits providing addressing human services needs. Efforts which, of course, are facing greater-than-ever demand for their services.

That’s one financial reality of a major property tax cut. The more significant one, however, is truly crazy, and rests on two realities.

Reality #1: Wyoming’s Constitution and laws mandate the levying of 43 mills of property tax.

Reality #2: Wyoming’s Constitution and laws mandate that assessed property values have to be within 5% of market value. Hence this year’s 40% increase in assessed values.

Combine the two, and even if every discretionary property tax were eliminated next year – even if the Teton County Commission, the Teton County School Board, St. John’s Health, and the Teton County Conservation District all agreed to levy zero mills of property tax – Teton County’s property taxes would still go up 6%.

Which raises a very interesting public policy question: How is the community best-served? By maximizing individual gain? Or by pursuing the collective good?

For example, let’s say that, in FY 2023, Teton County cuts its property tax levy by 50%. In such a case, the total tax bill facing Teton County’s property owner will fall by only 7%, raising the question: “How is the community best served: by 10,000 property owners each saving 7% on their tax bills, or by using the resulting $12.9 million to provide a variety of services that benefit the larger community, including some of its most vulnerable members?”

21st Century Community With a 20th Century Operating System

To answer questions like this, Jackson Hole needs to ask and answer a question it has never explicitly addressed: In our community, what is the proper role of government?

Historically, the answer has been shaped by Wyoming law, which ties government funding to a combination of property ownership and the very 20th century activities of going to the mercantile and digging stuff out of the ground. This mechanism produces a rather limited amount of revenue, resulting in local government being able to do little more than provide Core Services. Additionally, because of this focus on 20th century economic activities, Teton County’s governments can’t adapt to the more contemporary economic trends driving the community’s growth.

For example, in today’s Jackson Hole, untaxed real estate sales account for about 50% more gross revenue than taxable sales. Throw in the similarly untaxed professional services sector, and the figure goes up to about twice the level of taxable sales.

This disconnect between Wyoming’s 20th century operating system and Jackson Hole’s 21st century economy means there is little money available to address the challenges created by our very contemporary economy. Strikingly, these challenges include not only the obvious ones resulting from things like Teton County’s nation-leading income inequality, but also those facing property owners – Jackson Hole’s 21st century economy is causing property taxes to explode, creating real problems for those whose incomes aren’t growing as fast as property values (i.e., creating real problems for basically all of us).

Yet because Wyoming laws are so rooted in the mid-20th century, they don’t provide Jackson Hole the tools it needs – for example, a real estate transfer tax or the ability to offer property tax breaks for primary residences – to address its 21st century challenges.

Cutting the Gordian Knot

So what might we do?

Let’s start by acknowledging the obvious: Rapidly-rising property values have created a dilemma.

On the one hand, rising property values are fueling a concomitant rise in property tax revenues. These revenues are primarily benefiting Wyoming’s schools; to a lesser extent they are benefiting local government, health care, and conservation. Critically, those increased revenues are needed to offset the disruptions being caused by rising property values.

On the other hand, rising property taxes are creating a burden for those who aren’t extraordinarily wealthy. The well-to-do can afford to pay current Jackson Hole real estate prices and the concomitant property taxes. Those less well-off are struggling, particularly those long-time residents whose stewardship has made Jackson Hole such a desirable place to live.

Hence the paradox. How do we simultaneously help two struggling groups with diametrically opposite needs? One group needs greater amounts of tax dollars to address their needs, while the other needs their tax burden lowered. To make the challenge harder still, how do we accommodate both given the constraints of Wyoming’s 20th century operating system?

I can come up with one possible solution – imperfect, but not nothing: Link a reduction in property taxes to an increase in sales tax.

This isn’t an original idea. Instead, it’s just an updated version of what Ralph Gill championed 50 years ago. This time, the bargain would have two linked steps:

• In May 2023, ask voters to increase the local sales tax rate from the current 6% to the state-allowed maximum of 7%.

• If the vote is successful, the county commissioners would then cut in half the mill levy they control.

Doing this would have three positive results and one negative one.

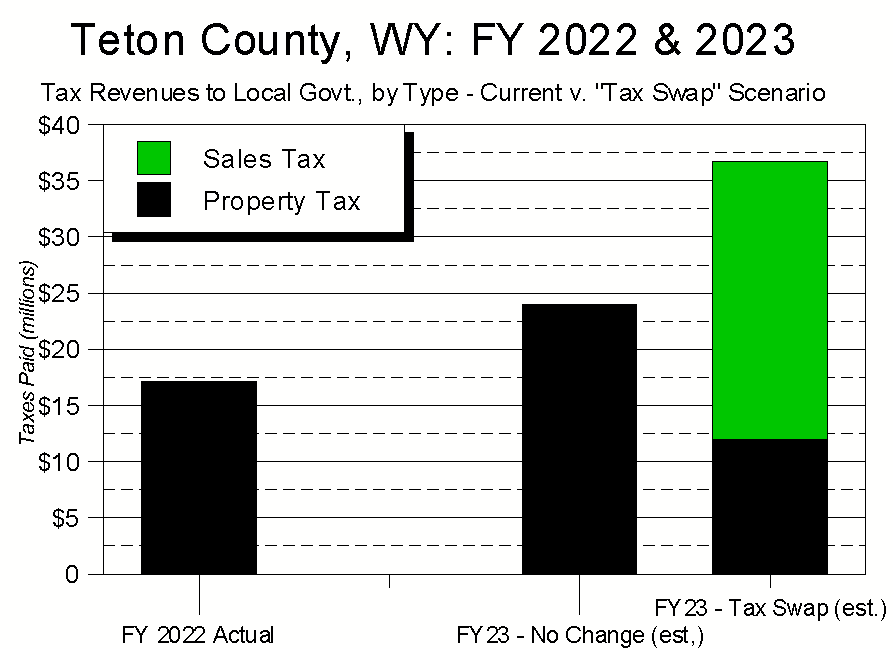

Positive result #1: Local government– both Teton County and the Town of Jackson– would receive more revenue.

Positive result #2: The overall tax burden on Teton County residents wouldn’t change – locals would pay about the same total amount of tax, just with a different split.

Positive result #3: Because tourists account for about 50% of Teton County’s total taxable sales, essentially all of the extra money flowing to local government would come from tourists.

The negative result would be that while property owners would see their property tax burden decline, all residents – whether or not they own property – would pay more in sales taxes.

Under this plan, a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the average property owner’s tax bill would go down around $1,000/year, and the average resident’s sales taxes would increase around $500/year.

So what will serve our community best? As I see it, there are three basic options.

Option 1 is to stay with the status quo –leave sales taxes and property tax rates where they are.

Under this option, property taxes will go up, and the county commission will have extra revenue for continuing to provide a mix of Core Services and support for things like housing and local social services non-profits.

Option 2 is that the county commission can lower the property tax rate, and in so doing keep property revenues flat or, perhaps more realistically, growing slower than they otherwise would.

With less money to work with and facing higher costs (due to both inflation and skyrocketing housing and labor costs), the county will have to tighten its belt, likely cutting back on things such as its support for housing and human services non-profits.

Option 3 is to swap a sales tax increase for a property tax decrease.

Under this option, local property owners will clearly benefit. But because that group includes both those of great means and those who are barely hanging on, by helping the latter we’ll also be using government policy to help the rich get richer (and they certainly don’t need any additional help…).

Making matters worse, those who don’t own property will find themselves paying more in taxes – and this at a time when inflation is already driving up prices.

Yet besides providing meaningful property tax relief to those who need it, this “sales tax for property tax swap” mechanism will also boost overall local government revenues between 10%-15%, allowing the county and town governments to provide greater services to the entire community, especially those in need of more assistance.

(Note: because of the town collects very little property tax, only option 3 will significantly affect the town’s finances.)

So what’s the right answer? I don’t know. Each option has merits, and I’m acutely aware of the many cross-currents involved in the issue, including the do-nothing option.

What I am certain of, though, is this. Raising the tax swap idea is a way of getting at the larger question of what role government should play in our community. That is a conversation worth having, and I look forward to hearing your thoughts.