Hello, and the happiest of holidays to you!

This newsletter celebrates the unique, focusing on two items that are truly one of a kind.

Item one is that the Town of Jackson has finally posted the job description for its there-is-no-other-job-like-it Ecosystem Stewardship Administrator position.

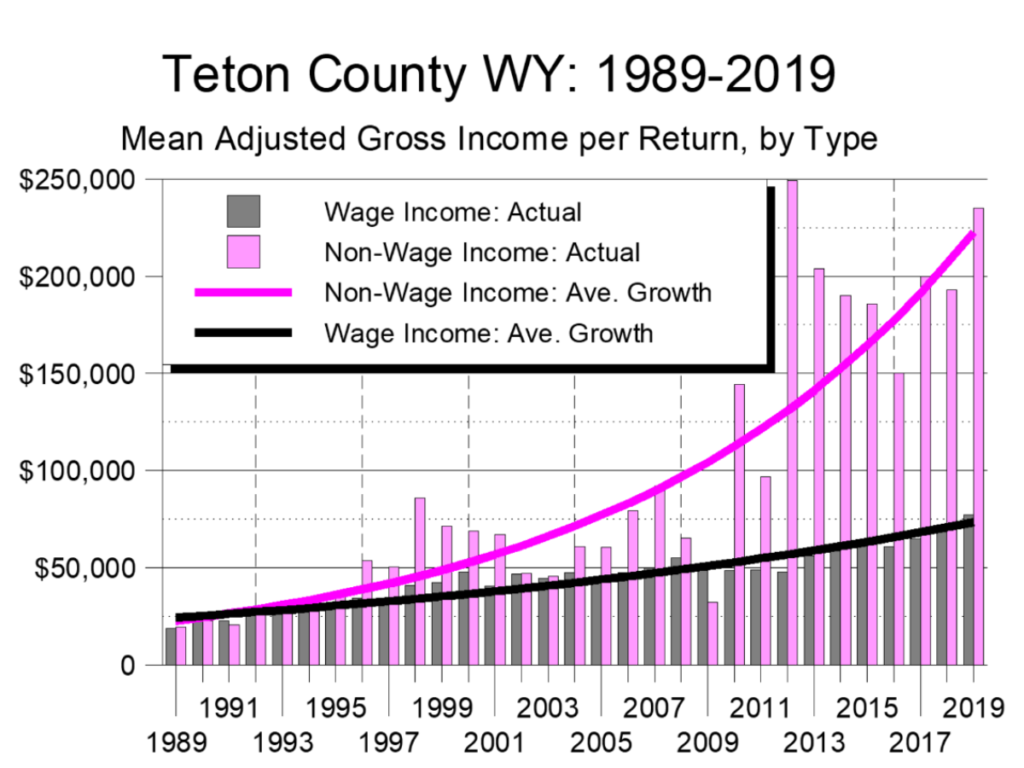

Item two is that the IRS has put out data showing that, in 2019, Teton County, Wyoming’s mean per-return Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) was $312,442. This not only led the nation, but marked the first time in US history that a county’s mean per-return AGI exceeded $300,000.

To put Teton County’s figure in perspective, in 2019 New York County, New York (aka the island of Manhattan) had the nation’s second-highest mean per-return income. It was $212,534, a full $100,000 lower per return than Teton County’s.

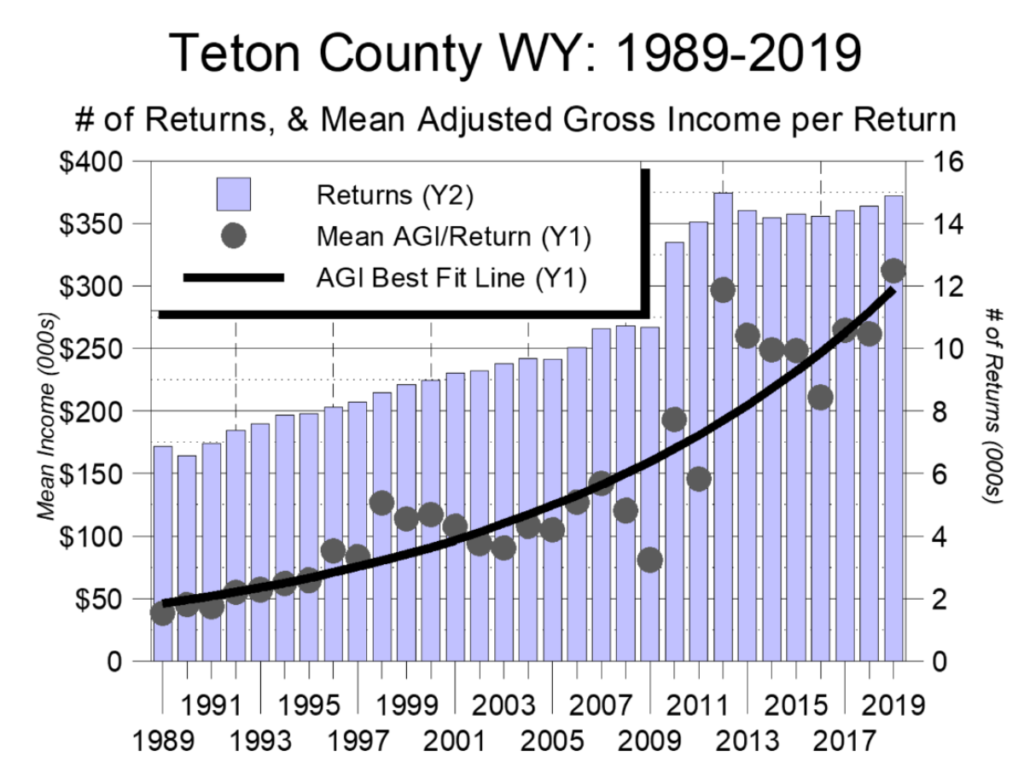

Perhaps more striking still, 75% of Teton County’s income comes from investments and other, non-wage income (the US average is 31%). In 2019, Teton County’s mean per-return non-wage income alone was $235,186, 11% higher than New York’s total income figure.

These are insane numbers. Yet what’s really nuts is that these figures are from 2019; i.e., the year before COVID-19 migrants started flocking to Jackson Hole. As a result, 2020’s numbers should be much higher, and 2021’s numbers nuttier still.

Bottom line: If it feels like things are not just crazy, but spinning-out-of-control crazy, there’s a good reason for it.

Table of Contents

- Ecosystem Stewardship Administrator

- 2019 IRS Data

- Basic data for Teton County, Wyoming

- Teton County v. the rest of America

- People moving out; people moving in

- Charitable giving: actual and potential

- America’s greatest income inequality

- Observations

Not-at-all-crazy are two deeply-held feelings of mine.

First, I hope 2022 proves to be a year of great happiness and deep contentment for you and all those you love.

Second, thank you so very much for your interest in, and support of, my efforts. Words cannot capture how much that means to me.

The happiest of holidays, and here’s to a wonderful 2022.

Cheers!

Jonathan Schechter

Executive Director

Ecosystem Stewardship Administrator

The Town of Jackson has finally posted the job description for our new Ecosystem Stewardship Administrator position. Applications are due on Friday, January 24, 2022, at 12 noon.

Here are links to the general job posting, as well as the complete job description.

To my eye, the most important sentence in the general job posting is this: “Any combination of education and experience providing the required skill and knowledge is qualifying.”

The significance of this sentence stems from the fact that, to the best of my knowledge, no other local government in America has a position like Jackson’s Ecosystem Stewardship Administrator. This is because no other community in America has a Comp Plan whose vision is anything like ours: “Preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem in order to ensure a healthy environment, community, and economy for current and future generations”

Because of this dual uniqueness, there is no mold or archetype for this hire. As a result, the richer and more diverse our applicant pool, the greater the chances of the Town of Jackson finding just the right person to create and make a success of this entirely new position.

Please feel free to share this information as widely as possible — not just with folks who might be interested in the position, but with anyone who might know people who might be interested.

2019 IRS Data

Each year, the IRS presents an astonishing amount of data about each county’s tax returns. For example, did you know that, between 2010-2019, the number of Teton County households whose income tax returns were classified as “Farm Returns” rose from 143 to170 (1.0% and 1.1% respectively)? Or that, in 2019, Teton County residents’ total tax liability was nearly $1 billion – $969 million, over twice 2010’s figure of $440 million? Neither did I.

The IRS provides so much data that I can focus on only a fraction of it:

- Basic data for Teton County, Wyoming

- Teton County v. the rest of America

- People moving out; people moving in

- Charitable giving: actual and potential

- America’s greatest income inequality

Basic data for Teton County, Wyoming

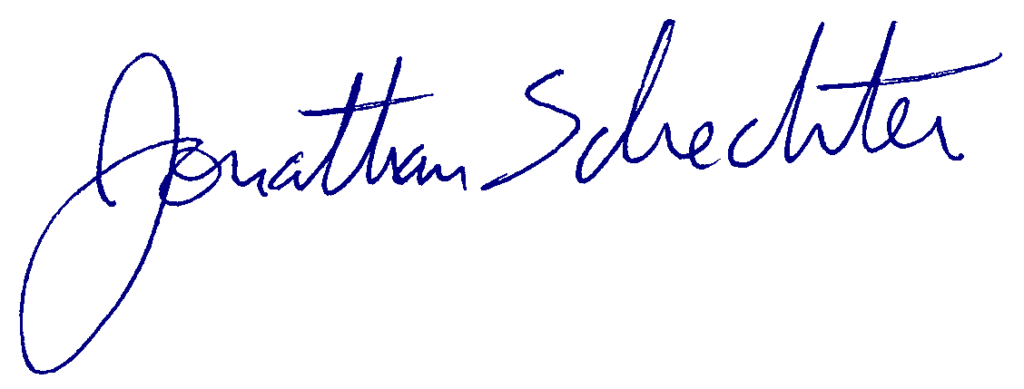

In the 30 years between 1989 and 2019, the number of income tax returns filed by Teton County residents more-than-doubled, from 6,875 to 14,870. During that same time, residents’ mean per-return AGI grew over eight-fold, from $38,339 to $312,442. (Graph 1)

As noted above, the 2019 mean per-return income figure was a record high not only for Teton County, but for any county in any year in the nation’s history.

The 30 year average annual growth rates were:

- Tax returns filed: 2.6%

- Mean total AGI: 7.2%

- Mean wage income: 4.8%

- Mean non-wage income: 8.6%

As a point of comparison, over this same 30 year period the average annual growth rate for the S&P 500 was 7.8%; for inflation, it was 2.4%. (Graph 2)

Teton County v. the rest of America

Comparing Teton County to the rest of America, two 2019 figures are especially striking.

First, between 2018 and 2019, Teton County’s mean per-return AGI rose by $50,942 (19.5%). During that same time, America’s mean per-return AGI fell from $75,695 to $75,694, a drop of $1 (0.0%)

As a point of comparison, in 2019 40% of all US counties – a total of 1,263 – had a mean per-return income of under $50,942; i.e., their mean per-return income was smaller than Teton County’s 2018-2019 increase alone.

Second, in 2019, Teton County’s mean per-return income figure of $312,442 was over four times greater than the national average of $75,694. To put that figure in perspective, let’s quickly return to the aforementioned gap between nation-leading Jackson Hole and second-place New York City.

in 2019, Jackson Hole’s mean per-return AGI was essentially $100,000 greater than New York City’s; to be precise, $99,908. In contrast, a nearly-identical $99,732 gap separated second-place New York City and 63rd place Delaware County, Ohio, a wealthy suburban area bordering Columbus OH.

Same dollar difference. One place between us and New York. Sixty two places between New York and Delaware County.

Historically, the only county that has come even close to matching Teton County’s income has been New York, NY. New York led Teton County until 1994. Since then, Teton County’s per-return income has exceeded New York’s every year save two: 2009 and 2011. (Graph 3)

People moving out; people moving in

One of the many sources of angst washing over Jackson Hole is a sense that the community is being decimated by turnover, with new arrivals pricing out long-time residents. While IRS migration data shed some light on this, please note that we won’t know the extent of COVID-related migration until 2020’s data are released a year from now.

In its reporting, the IRS lumps all taxpayers into three migration-related categories:

- Non-migrants; i.e., people who live in the same county two years in a row.

- In-migrants; e.g., those who lived outside of Teton County in 2018, and in Teton County in 2019.

- Out-migrants; e.g., those who lived in Teton County in 2018, and outside Teton County in 2019.

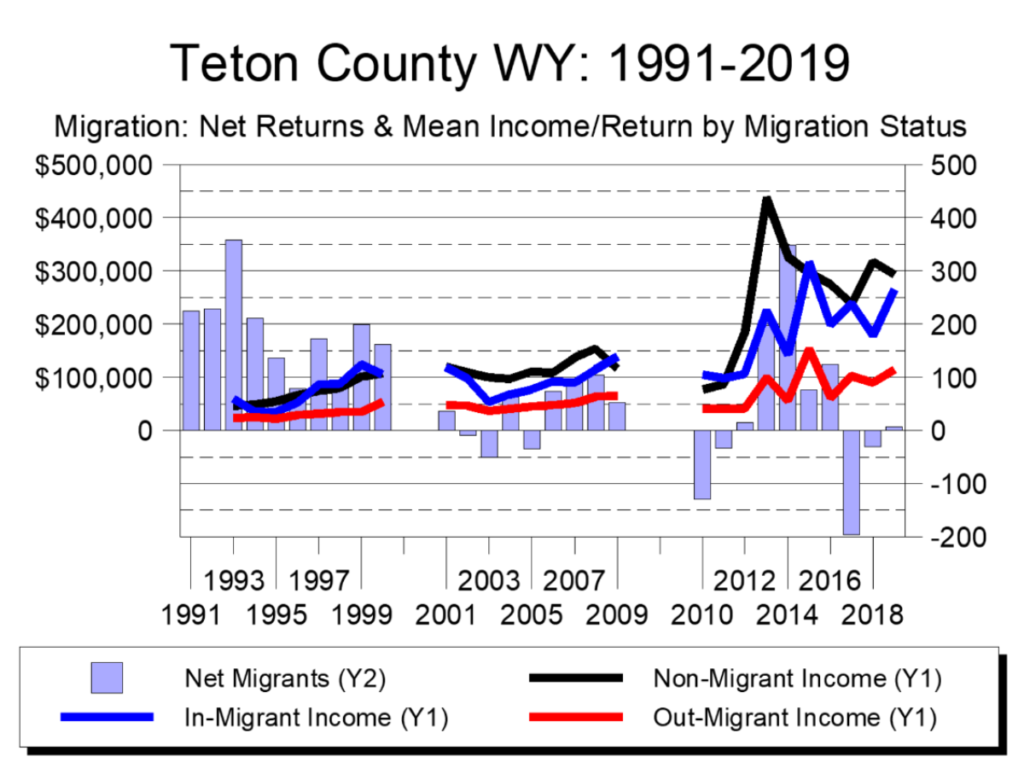

Migration data go back to 1990-1991, with income data provided from 1993 on. Broadly speaking, during those 28 years Teton County has experienced three migration phases, roughly coinciding with the past three decades.

Phase I was the 1990s. Call this the “population growth” phase. Each year, hundreds more households moved to Teton County than left, and the newcomers made about as much money as those already living here. Which was about twice as much as those leaving Teton County.

Phase II was the 2000s. Call this the “stasis” phase. Far fewer people moved here, and all three income figures – non-migrant, in-migrant, and out-migrant – were about the same at the end of the decade as they were at the beginning.

Phase III was the 2010s. Call this the “income growth” phase. This past decade was hallmarked by two qualities: volatility in migration patterns, and a huge explosion in income growth. It was also the first decade in which, for every year, the income earned by in-migrants was at least twice that of out-migrants.

In 2019, the mean per-return income for Teton County’s non-migrants was $169,719. For in-migrants, it was $265,413; for out-migrants it was $115,134. To put that latter figure in context, in 2019 only 49 US counties – 1.6% – had mean per-return incomes higher than that of the households leaving Teton County.

Combined, the migration-related data seem to support our migration-related angst, not to mention the quip about billionaires crowding out millionaires. (Graph 4)

Charitable giving: actual and potential

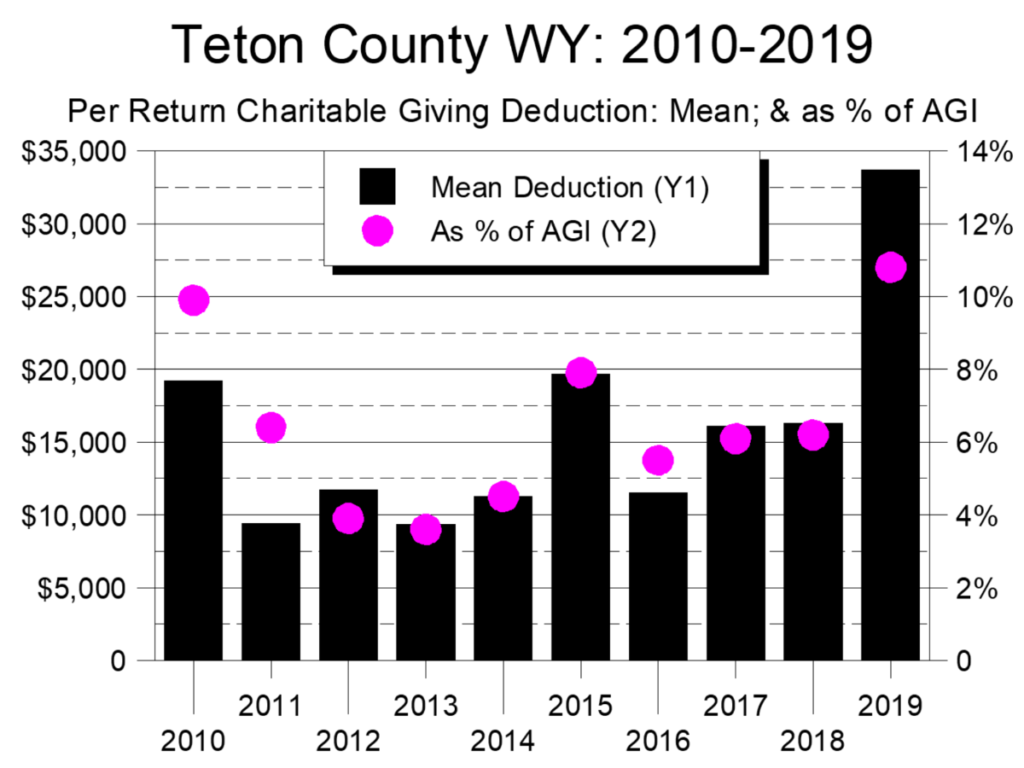

The IRS has made charitable contribution data available since 2010. Each year, Teton County has recorded the nation’s highest per-return charitable contribution figure. 2019’s $33,710 was the highest per-return contribution figure ever recorded, a full 72% higher than Teton County’s 2015 figure of $19,646 (the previous high).

Overall, in 2019 Teton County residents claimed 10.8% of their total AGI as charitable contribution. This, too, led the nation, the first time we’d done so. (Graph 5)

This extraordinary generosity raises two obvious questions.

First, how much of residents’ giving goes to local nonprofits?

Unfortunately, there is no direct way of answering that question. We can surmise, however, that because Teton County residents claimed a total of $501 million in charitable donations in 2019, most of residents’ giving is targeted at nonprofits outside the community (as total charitable contributions to local nonprofits are too small for a figure as large as $501 million to make sense).

Second, do residents have additional giving capacity?

At one level, it doesn’t seem possible, for as noted above, in 2019 Teton County led the nation in both mean donation amount and donations as a percentage of AGI.

That noted, it’s also true that between 2018 and 2019, residents more-than-doubled their total charitable giving. They also donated a much bigger percentage of their AGI than before.

Equally intriguing, until 2019 Teton County residents donated a smaller percentage of their AGI than did residents of some other counties.

More striking still, Teton County has never led the nation in percentage of non-wage income donated to charities, and has never come even close. In 2019, we were 9th in the nation in charitable donations as a percentage of non-wage income; before then, we barely averaged being in the top 1,000 of all counties.

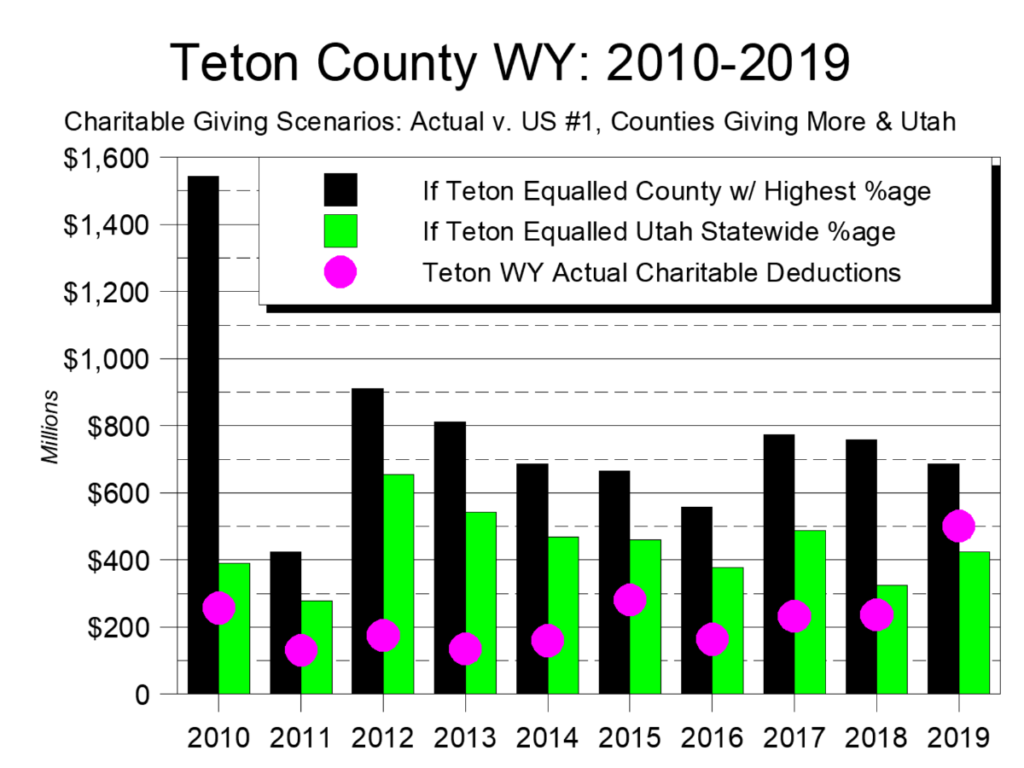

Graph 6 compares Teton County residents’ charitable donation levels as a percentage of non-wage income to two benchmarks:

- each year’s leading county; and

- the state of Utah (which annually leads all states in its percentage of non-wage income donated to charity).

Bottom line? If Teton County’s already-generous charitable givers donated their investment income at the same levels as residents of the nation’s leading county and/or state, they’d have donated several hundred million more dollars annually than they actually did.

Combine this with the big leap in residents’ donations between 2018 and 2019, it seems likely that Teton County’s residents have greater charitable giving capacity than is currently being realized.

America’s greatest income inequality

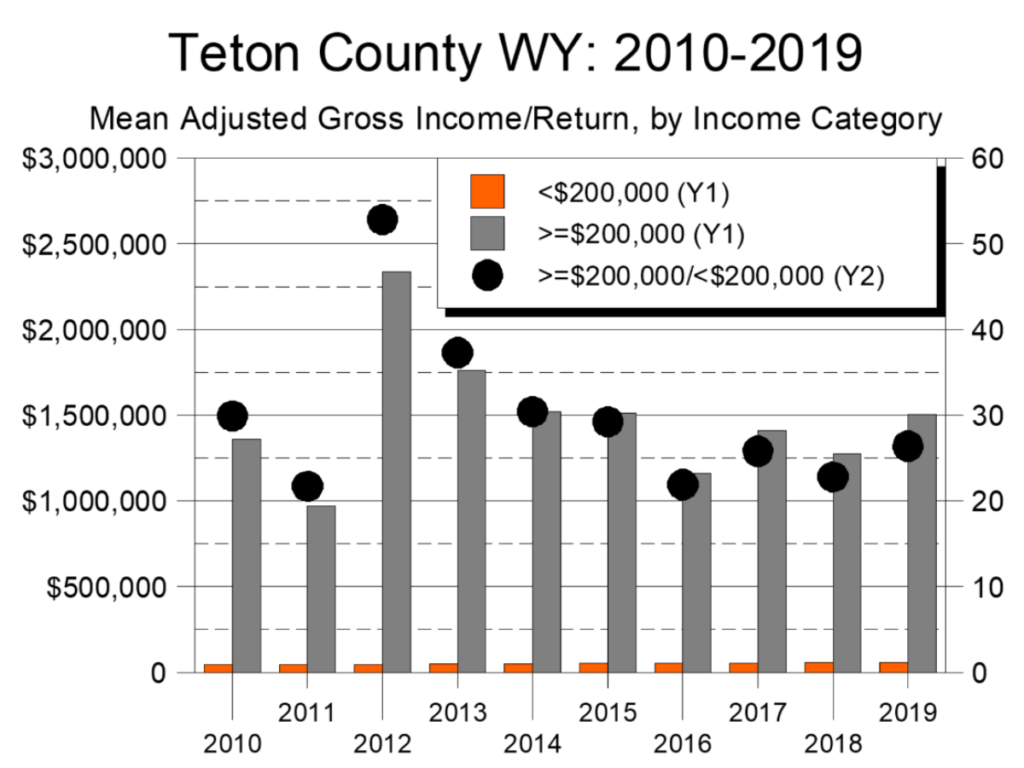

As I first reported many years ago, historically Teton County has had the nation’s greatest income inequality. In 2019, this streak continued.

Since 2010, the IRS has broken every county’s tax returns into income brackets, with the highest bracket recording returns with AGIs of $200,000 or more.

In Teton County in 2019, 2,630 returns – 18% – had AGIs of $200,000 or more. These returns had a mean per-return income of $1,5 million, and accounted for 85% of the community’s collective income. The 82% of returns with AGIs of under $200,000 had a mean per-return income of $56,909, 1/26 that of those earning $200,000 and more. (Graph 7)

And again, these figures end in 2019; i.e., before Jackson Hole’s influx of COVID-19 migrants. As a result, these inequality figures have almost certainly grown in the past two years.

Observations

Sustainability involves three types of capital: environmental, economic, and social. As 2021 flows into 2022, Jackson Hole is unique in two of them: we sit at the center of the largest generally-intact ecosystem in the lower 48, and we have the highest mean per-return income of any county in American history.

Moving beyond 2022, however, it’s not clear whether we will retain both of these unique qualities.

Economically, there’s no doubt about Jackson Hole’s future. Given COVID-related migration, the worldwide explosion of remote working, and Wyoming’s tax-friendly legal structure, Teton County will clearly continue to enjoy record-setting wealth.

Much less certain, however, is whether we can maintain our environmental health.

We face what I’ve come to think of as the “Eco/Eco Dilemma.” The first “Eco” is Economic Development; the second is Ecosystem Health. The dilemma lies in the sad fact that, since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago, every place on Earth that has developed a successful industrial or post-industrial economy has, in the process, compromised the health of its ecosystem.

The one exception? Contemporary Jackson Hole and, more broadly, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

So what might happen?

On the one hand, Jackson Hole sits at the heart of the largest generally-intact ecosystem in the lower 48. Further, ecosystem stewardship is the foundation of our Comp Plan. Better still, we’re acting on that commitment – most recently through the creation of the town’s Ecosystem Stewardship position. This is truly great stuff.

On the other hand, there’s the Eco/Eco Dilemma.

In particular, recent growth patterns strongly suggest that the Tetons region – especially the counties absorbing Jackson Hole’s growth-related pressures – will succumb to the same pressures that have compromised ecosystems across the planet for the last 250 years. Indeed, despite Jackson Hole’s location at the headwaters of the Snake and Columbia river basins, two local streams are currently classified as “impaired” by Wyoming’s Department of Environmental Quality – not a good omen.

Making matters more complicated still, because no place on Earth has ever figured out how to solve the Eco/Eco Dilemma – i.e., ever figured out how to simultaneously develop a successful contemporary economy and maintain a healthy ecosystem – there is no blueprint for Jackson Hole to follow in its quest to “preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem.”

Without a blueprint, what will it take for us to solve the problem on our own? Two things:

- A shared sense we’re in this together; and

- A shared sense of the opportunity at hand.

We’re in this together

Throughout much of its history, living in Jackson Hole required making sacrifices. For some residents, this meant forsaking income and career opportunities. For others, it was being away from family and friends; for still others, not having access to cultural and consumer opportunities. Something about the place, however, made those sacrifices worth it, and that sense of shared sacrifice knit the community together.

Over the past 30 years or so, though, changes in technology, the economy, transportation, and mores have steadily eroded the need to make sacrifices. As a result, today it’s possible to live in Jackson Hole and truly “have it all” – an extraordinary lifestyle in an extraordinary setting without making any meaningful sacrifices.

Well, at least some of us can have it all. But when 18% of households are making 85% of the community’s income, not everyone is having it all. Far from it.

So if a sense of shared sacrifice can no longer knit us together, what can? In my view, our best opportunity is to collectively commit ourselves to solving the Eco/Eco Dilemma; to collectively commit ourselves to figuring out how we can continue to have both a thriving economy and a thriving ecosystem. For unless we can do that, we put at grave risk all that makes this region and community exceptional.

The opportunity at hand

Solving the Eco/Eco Dilemma may be an audacious goal, but our region’s history is replete with examples of people and organizations not just pursuing audacious goals, but achieving them. More striking still, these efforts have occurred in 50 year cycles, and we’re coming to the end of the most recent one.

In particular:

- March 1, 2022 will mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of Yellowstone, the world’s first national park. In the 1870s, creating a national park was an audacious idea, if not a truly radical one. Yet today we see it as one of history’s great no-brainers.

- In the 1920s, John D. Rockefeller Jr. began the process of buying 35,000 acres in the Jackson Hole valley, which eventually became part of Grand Teton National Park. Again, a truly radical idea. Again, an idea appropriate to the times. Again, an idea which has more-than-stood the test of time.

- In the 1970s, the first conservation easements were placed on Jackson Hole properties. Viewed as radical at the time, the concept has become so broadly accepted that today more than 30,000 acres of land is protected in Teton County, Wyoming, and another 67,000 acres in the counties surrounding Teton County.

Our current decade marks 50 years after the last big initiative was launched, presenting today’s generation of Tetons residents with our opportunity to leave a meaningful legacy.

To leave a meaningful legacy will require us to be bold, but the same was true for our forbears 50, 100, and 150 years ago. As we proceed, though, our boldness needs to be tempered with humility, in particular a recognition that everyone who has chosen to live in the Tetons region has, whether consciously or not, also chosen to be a steward of this extraordinary place; a place which, as the National Park Service Organic Act puts it, is worthy of being conserved and left “…unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Can we successfully address the Eco/Eco Dilemma? As was true for previous “50 year challenge” folks, the answer isn’t clear. Unfortunately, 250 years of precedent suggest the answer will be “no,” because after 250 years the Eco/Eco Dilemma remains unsolved. Making things more challenging still is the fact that seemingly every economic incentive is pushing us towards ecosystem-harming types of development; in particular towards providing increasingly expensive homes, services, and other products to the folks who can afford them.

Arguing for success, though, is Jackson Hole’s history of innovative conservation, and our deeply embedded passion for conservation.

This is an incredibly strong foundation upon which to build. Add in our extraordinary wealth and extraordinary philanthropy, as well as our potential for donating even more, and our generation has the raw materials in place for making a truly meaningful contribution to the region’s historic 50 year pattern.

To be clear-eyed about our opportunity, we won’t be able to figure out how to thrive economically and ecologically unless we consciously set out to do it. And even if we do, there’s no guarantee of success. But similar challenges were faced by those who founded Yellowstone, expanded Grand Teton, and set out to conserve Jackson Hole’s private lands. How incredibly great would it be for this generation to take its place among that pantheon?

As we move into 2022, here’s hoping we rise to the occasion.