Hello, and welcome to the first edition of the CoThrive blog.

CoThrive will replace the Corpus Callosum column I no longer write for the Jackson Hole News&Guide. Like that column, it will examine issues affecting Jackson Hole, the greater Tetons/Yellowstone region, and similar communities outside our region.

For the remainder of 2019, CoThrive will be offered without charge. If you would like to subscribe, please click here.

The research and analysis underlying CoThrive is representative of the fact-based, action-oriented work my Charture Institute does. If you would like to support our work, please click here to make a tax-deductible donation to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run.

Below, you’ll find that this initial edition of CoThrive is divided into four parts:

- Some background on CoThrive (click here)

- The logistics of CoThrive (click here)

- This month’s main essay: The Jackson Hole Paradox: Big City Traffic and Jobs; Small Town Population (click here)

- An addendum with additional information I unearthed researching this essay (click here)

Thank you so much for your interest in Charture. I look forward to your feedback, and thank you in advance for supporting our work through Old Bill’s Fun Run.

Cheers!

Jonathan Schechter

Please support our work by donating to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run

To contact us, please call (307) 733-8687, or e-mail js@charture.org

CoThrive: Background

In late May, 2018, I announced my candidacy for Jackson’s Town Council. When I did, the Jackson Hole News&Guide and I agreed to suspend my Corpus Callosum newspaper column until after the election.

Happily, I won my race, but being an elected official creates its own conflicts. As a result, until I leave office, I will not be writing for the News&Guide.

Hence this blog: CoThrive. Its organizing principle will be an idea I’ve become increasingly obsessed with over the past few years: To the best of my knowledge, since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago, Jackson Hole is the only community, region, or nation on Earth to develop a successful post-agrarian economy without fundamentally compromising the health of its ecosystem.

That’s a remarkable concept. At a number of levels. Both locally and globally. Yet at its most elemental level, this only-place-in-250-years idea illuminates the most fundamental fact about our community: If Jackson Hole wants to continue to thrive as a human community, we have no choice but to figure out how to keep our ecosystem healthy.

Unfortunately, there is no roadmap for us to follow. Indeed, 250 years of history suggest we’ll fail in that effort. Rather than succumb to pessimism, though, I decided to launch CoThrive as a real-time tool to help all those who care about this region figure out that which no community has ever done before.

And if we get it right, our roadmap can become a guide for other places looking to co-thrive.

“Co-thrive” is a term I coined to describe the state in which a human community and the ecosystem in which it lies simultaneously thrive. Building on this theme, the CoThrive blog will primarily focus on the Tetons region’s human community, its ecosystem, and the nexus between the two. Because the issues facing the region are so complex, however, and because no one really knows how to achieve a state of co-thriving, I’ll also use the CoThrive blog to explore ideas and events outside the bubble that is the greater Tetons/Yellowstone region.

Please support our work by donating to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run

To contact us, please call (307) 733-8687, or e-mail js@charture.org

CoThrive: Logistics

CoThrive is a logical extension of the work of my Charture Institute, whose five-part focus is “Learn. Teach. Inspire. Act. Fund.”

My hope had been to launch CoThrive months ago, but the drinking-from-a-firehose quality of learning my Town Council job has proven nearly all-consuming. One result is that I don’t know how frequently I’ll be able to produce new editions of CoThrive. My desire is to produce at least one lengthy analytical piece per month, with additional smaller features offered on an irregular basis. Whether the actions of the flesh can match the willingness of the spirit, though, remains open to question.

Because of this uncertainty, for the remainder of 2019 CoThrive will be offered for free. That will give the blog four months to hit its stride, allowing us to figure out both a publishing schedule and a pricing model that work for both the readers and us. Until then, enjoy it with our compliments.

That noted, while CoThrive may be free to readers, it is not free to produce. Far from it. To support this work, Charture Institute accepts tax-deductible donations – please click here to do so through Old Bill’s Fun Run.

Old Bill’s matches donations to its recipients. Old Bill’s donations are accepted through 5:00 pm MDT on Friday, September 13.

Please support our work by donating to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run

To contact us, please call (307) 733-8687, or e-mail js@charture.org

CoThrive: Main Essay

The Jackson Hole Paradox:

Big City Traffic and Jobs; Small Town Population

Around dinnertime a couple of weeks ago, I drove east on Snow King Avenue. Heading west were three-quarters of a mile of bumper-to-bumper traffic, stretching from Scott Lane to the Fair Grounds.

To tell you what you already know, the same thing happens in Jackson Hole pretty much every day, especially on the highways in and out of town. And often in both directions. And, increasingly, not just in summer. Clearly we have a traffic problem, and that got me wondering about its root causes.

Here’s my basic conclusion. Jackson Hole creates jobs like a big city, resulting in big city traffic problems. Because we have the population of a small town, though, we lack the critical mass of people needed to make mass transit work well.

Exacerbating this job-production reality is our tourism economy. Combine our jobs-created traffic plus that generated by thousands of tourists and the result is an extraordinarily vexing transportation problem.

Special challenges, and a unique challenge

Jackson Hole is not the only place facing traffic problems, of course – we’re special, but not unique. Indeed, we face the same suite of problems facing every other special place to live on the planet, including traffic, affordable housing, and issues related to increasing wealth inequality.

On top of these special problems, Jackson Hole also faces a truly unique challenge: Preserving the health of our ecosystem. To the best of my knowledge, Jackson Hole is the only place on Earth that currently has both an advanced post-agrarian economy and a basically intact ecosystem. Making matters more complicated still is a further reality: No blueprint exists for successfully addressing any of the challenges we face, whether special or unique.

Rather than despair, let’s take the first step needed to successfully address any problem and examine the root causes of our traffic issues.

Jackson Hole’s “peers”

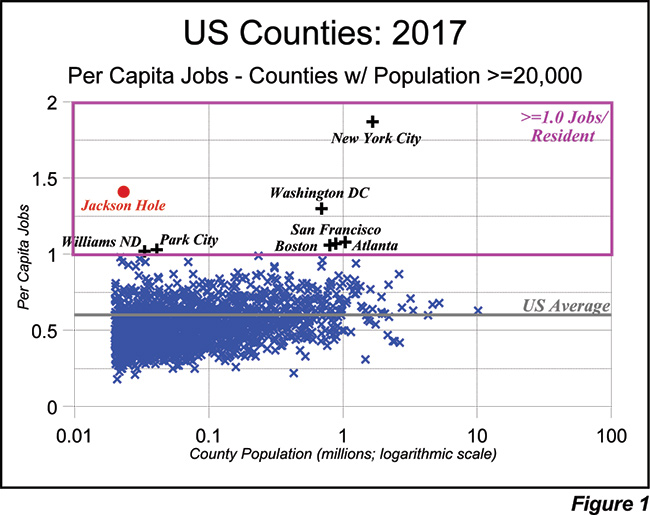

Context is important, and among the 3,113 counties in the United States, Teton County, Wyoming is one of 1,815 – 58 percent – with a population greater than 20,000.

I’m focusing on these more-populous 1,815 counties because they are home to 96 percent of the nation’s population and 97 percent of its jobs. Do the math, and in 2017 America as a whole averaged 0.60 jobs for every U.S. resident, be they child, retiree, chronically unemployed or actively in the workforce. In counties with a population greater than 20,000, the per capita job figure was a bit higher: 0.61 jobs per resident. In the less-populated counties, the figure was lower: 0.50 jobs per resident.

In 2017, eight of the 1,815 more-populous counties – 0.4 percent of the total – had more than one job per resident. Leading the way was New York County, New York, the island of Manhattan, with 1.87 jobs per capita (each of New York City’s five boroughs is also its own county – Figure 1).

New York’s per capita jobs figure is so high – three times the national average – because around two million people pour into New York City every day to work, only to return each evening to their home outside of Manhattan. And because some 20 million people live in the greater New York City metropolitan area, both financially and logistically the region can afford to have a large and effective multi-modal mass transit system.

Ditto four of the other seven counties with more than one job per resident: Washington DC (1.30 jobs/resident, and 6.3 million people in the metropolitan area), Atlanta (1.08 and 5.9 million), San Francisco (1.07 and 4.7 million), and Boston (1.06 and 4.9 million).

Ranking seventh among the eight more-populous counties with more than one job per resident was Summit County, Utah, with 1.03 jobs per resident. Summit County is the location of Park City, and its job count is a reflection of the fact that tourism is a labor-intensive industry. Happily for that community, because it is part of the Salt Lake City metropolitan area (population 2.4 million), Park City has access to some, although by no means all, of the mass transit solutions available to big cities.

In eighth place, at 1.02 jobs per resident, was Williams County, North Dakota, the epicenter of the Bakken Basin oil boom. In 2007, Williams County had 0.75 jobs/resident; five years later, 1.51 jobs/resident; five years after that, 1.02. This is a classic boom/bust pattern, and when an economic slowdown occurs, the resulting decline in oil prices will likely lower Williams County’s job figures.

And then there’s Jackson Hole.

Jackson Hole

In 2017, among America’s 1,815 counties with a population greater than 20,000, Teton County had the second-most jobs per capita: 1.41. More jobs per resident than Washington DC. Or Atlanta. Or San Francisco. Or Boston. Or, saving New York City, any other American county with more than 20,000 residents.

Yet rather than being home to millions of people, our “metropolitan area” has around 45,000 residents; i.e., about one percent (if that) of most other job-producing Meccas. And with a population our size, it is profoundly difficult to run an affordable and well-utilized mass transit system.

Hence we get traffic. Lots and lots of traffic. How much?

Hard to say exactly, but along with more than one job per resident, we also have more than one vehicle registered per resident. And over the last ten years, our total vehicle miles traveled have increased faster than our population.

Making it harder still to run an affordable and well-utilized mass transit system in the Tetons region are two additional realities.

Two additional realities

The first is population density. Teton County’s population is not only a mere fraction of major metropolitan areas’ populations, it’s also far more dispersed. For example, the private lands in just the southern half of the Jackson Hole valley can hold two islands of Manhattan. Yet in an area that could hold 3.3 million New Yorkers you’ll find only about 10,000 Jackson Hole residents. This means Manhattan’s population is 330 times more dense than ours, and its subway system alone serves around 1,800 times more riders than does START.

The point is that if you have New York’s population density, you can make an effective mass transit system work both logistically and economically. In contrast, if you have Jackson Hole’s population density, it’s much, much harder.

Second, even if you have a small population, it’s still possible to do effective mass transit. Case in point: Butte County, Idaho. Located four counties to our west, Butte County has the greatest number of jobs per resident of any US county. Its population is tiny, just 2,600 or so. But because Butte County is the location of the Idaho National Lab (INL), in 2017 it had over 8,600 jobs – 3.3 per resident.

Yet here’s the crazy thing. Despite having a population only one-tenth that of Teton County, Wyoming, Butte County has a great mass transit system. Or, more precisely, INL has a great mass transit system, serving thousands of people daily on five different routes.

What makes this possible is that the INL bus system is a hub-and-spoke model: Buses from all over the region head to one place at about the same time each morning, then reverse the process each afternoon.

Contrast that to our situation in Jackson Hole. With the exception of Teton Village in the winter, our region has no major employers, hubs, or times of day with overwhelming peak demand. Instead, we have lots of employees coming from different places, going to different places, and doing so at different times of day. Ditto people who are out-and-about for non-work reasons.

To serve this kind of population requires a point-to-point system – think of New York’s subways. Such systems work well if they serve a population of millions and have a ridership of billions. They can’t, however, if those population and ridership numbers are chopped into not just percentages, but fractions of percentages.

Why so many jobs?

To take this analysis to another level, why are we such a job-producing machine? A large part of it has to do with tourism.

Tourism is extraordinarily labor-intensive, and in 2017, 36 percent of all of Teton County, Wyoming’s jobs were in the four main tourism-related industries of retail, recreation, lodging, and restaurants. This 36-percent-of-all-jobs-in-tourism figure ranked Teton County 19th among the nation’s 3,100+ counties.

Drilling a little deeper, in 2017 nearly one-quarter of all of Teton County’s jobs were in the combined category of lodging and restaurants, over three times the national average and ranking us 11th out of all US counties. We’re similarly strong in the “Arts, Entertainments, and Recreation” category, where our five percent figure – over twice the national average – ranked us 49th overall.

This matters because one hallmark of tourism-related jobs is the odd hours they require. The bakers at Persephone arrive to work not too much later than the bartenders at the Cowboy head home, and not only do they work far apart from one another, the chances are they live far apart. Apply that reality to each of our 12,000 or so tourism jobs, and from a mass transit perspective it creates the worst of all possible worlds: a ton of workers going and coming to different places at different times, yet without the critical mass needed to allow for effective public transportation solutions. So they, like so many of us, rely on their cars.

The one tourism-related employment category where we aren’t in the nation’s top one percent or so is retail. Despite the industry’s prominence in Jackson Hole – it’s the single biggest generator of local taxable sales – just eight percent of Teton County’s workforce is employed in retail jobs, 20 percent below the national average.

One other area of note regarding employment and traffic is that the second biggest single employment category in Teton County is construction, which accounts for roughly ten percent of our jobs. This ranks us in the top eight percent of all US counties, and before the recession we were in the top four percent. Why does this matter? Because contractors need their trucks, and Teton County’s roughly 3,000 construction jobs put a lot of vehicles on the road every day.

On top of all this, of course, is the traffic generated by our tourists. But the point these data make is that the combination of four factors – Teton County’s prodigious job-creation engine, our small population, our limited amount of private land, and the constraints we face regarding our transportation infrastructure – means traffic-related woes will be with us for some time, regardless of our tourism situation.

What to do?

So what do we do? If we had the population base of other major per-capita jobs communities such as New York or Boston, we could build a crackerjack mass transit system. But if we had that kind of population base, we wouldn’t be Jackson Hole.

Alternatively, we could try to improve our road system, but at this point its basic contours are pretty well set. Plus, because of our where we’ve put our houses and businesses, it would be pretty hard to do much more than merely tinker with our current road system.

And even if we do add new roads or widen existing ones, it’s wishful thinking to believe this will “solve” our traffic problem. This is because, as has been shown in city after city, whatever congestion relief new roads produce is quickly negated by a phenomenon called “induced demand,” which shows that regardless of how big you make a new road, its traffic will eventually expand to fill it to capacity once again.

Two lousy choices

This leaves just a couple of choices, neither of them great.

One is to fundamentally alter our approach towards mass transit and parking. This will cost a lot of money, though, and almost certainly require a tax increase of some sort.

This begs a fundamental question. What do Jackson Hole residents like less: traffic congestion or higher taxes? If it’s the former, there are clearly steps we can take, including developing a low-cost, expansive, and frequent bus system; congestion pricing for our roads; paid parking; and a vigorous alternative transit system. But such solutions are not cost-free – far from it. So if what really matters most to Jackson Hole residents is keeping our personal tax burden among the nation’s lowest, then we need to accept traffic congestion.

Put another way, we’ve had Champagne tastes and a beer budget for decades now, and traffic is the most obvious symptom of why that can’t continue.

Following this thought process through to its logical conclusion, if, after a thoughtful debate, the community decides lower taxes are more important than less traffic, then the only other realistic choice we have is to acknowledge that greatly increased traffic is an unfortunate but inescapable consequence of our astonishing economic success. While many long-time residents can remember when traffic wasn’t much of a concern, and while others have moved to Jackson Hole to get away from the types of problems exemplified by traffic jams, the reality is that today’s traffic is part of the price we’re paying for our economic vibrancy. And if we don’t want to buy our way out of those problems, recalibrating our traffic-related expectations may be our only other alternative.

Please support our work by donating to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run

To contact us, please call (307) 733-8687, or e-mail js@charture.org

CoThrive: Addendum

To produce pieces like The Jackson Hole Paradox, I start with basic research.

Sometimes such research proves to be profoundly meandering and excruciatingly inefficient, especially when it takes me down data-mining cul-de-sacs that don’t prove useful. More often than not, though, my research produces little nuggets I find really interesting, but which don’t neatly fit into what I end up writing.

This need to edit was a real problem when I was writing for the Jackson Hole News&Guide, because columns were so space constrained that I invariably left at least a few interesting snippets on the editing room floor. Because the blog format allows me more room, however, I thought I’d use addenda like this to include items that strike me as interesting, but don’t naturally flow into the final cut. In this case, as I researched jobs I came upon the following.

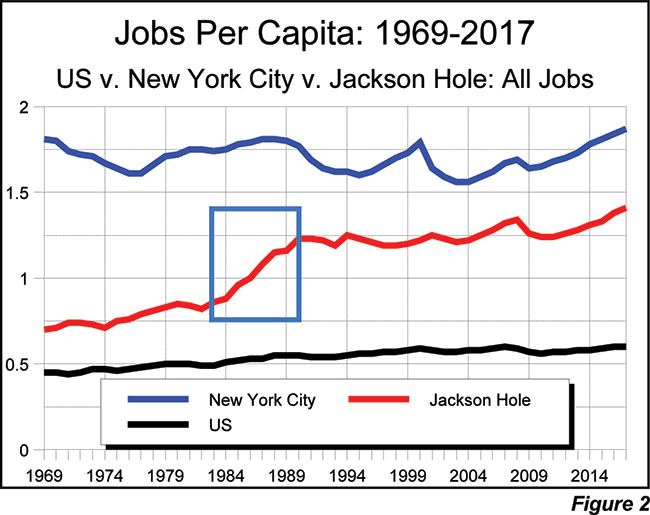

New York City has about three times as many jobs per resident as does the US. Teton County, Wyoming has about twice as many. This wasn’t always the case, though.

As Figure 2 shows, on a per capita basis, Teton County’s job situation really shifted in the 1980s. Up until 1980 or so, per capita jobs grew at a steady pace. After leveling off in the early 1980s, the per capita job number skyrocketed, growing from 0.82 in 1982 to 1.23 in 1990. Then, save for the recession, things continued their pace of slow-but-steady growth.

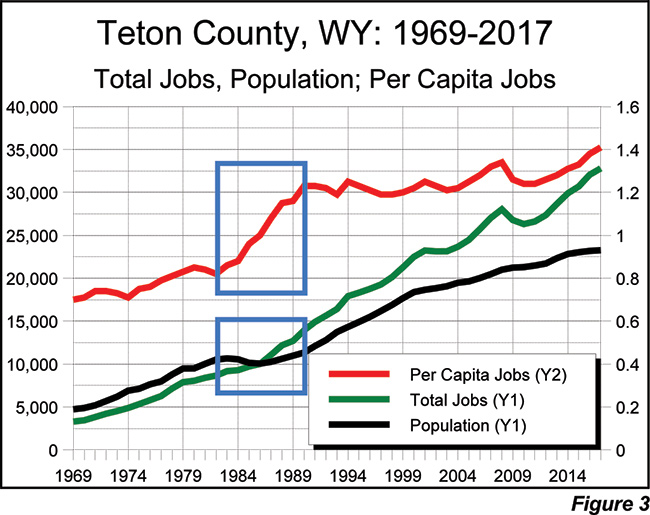

What happened? As Figure 3 shows, the answer lies not in the numerator (i.e., the number of jobs), but in the denominator; i.e., Teton County’s population.

In 1982, Teton County’s population totaled 10,653, its highest ever to that point. Starting in 1983, though, the population began declining, and would not return to 1982’s level for seven years.

In 1990, Teton County’s population went above 11,000 for the first time. The 1990 total of 11,328 means that, on a compounded basis, Teton County’s population grew just 0.8 percent/year between 1982-1990. In contrast, during that same eight year stretch, the number of jobs in Teton County grew from 8,650 to 13,924, a compounded annual growth rate of 6.1 percent.

As the 1990s began, Jackson Hole entered into its current post-tourism economic era. In fact, 2016 marked 30 consecutive years of population growth for Teton County. Even more remarkably, with the exception of the two immediate post-recession years of 2009 and 2010, the number of jobs in Teton County’s has grown every year since 1969.

Put another way, barring a catastrophic occurrence in the last five months of this year, 2019 will mark the 48th year in the last 50 that Teton County’s job market has grown. In contrast, in that same 50 year stretch, the United States has seen job declines five separate times.

Before 1990, Teton County’s economy was deeply dependent upon tourism, a reality best exemplified by the fact that, in the mid-1980s, Teton County’s leaders were so concerned about local tourism’s future that they lobbied Wyoming’s legislature to create the state’s first-ever lodging tax.

In 1990, though, construction surpassed government as Teton County’s third-largest job-creating industry. And by the end of the 1990s, the number of jobs in the Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate sector (FIRE) eclipsed those in government. Viewed another way, as late as the mid-1970s, Teton County has more jobs in agriculture and government combined than we had in construction, finance, and real estate combined – more ranchers and rangers and lawmen, if you will, than nail-bangers, bankers and real estate agents. By 1990, that had changed, creating a different take on “The Last of the Old West.”

The data also reveal another fascinating shift in Teton County’s economic history: the increasing importance of self-employment.

In 1969, 83 percent of Teton County’s jobs were wage and salary jobs, with the remaining one-sixth held by self-employed people (many of whom were ranchers). Jump ahead a generation, and that ratio really hadn’t changed much: in 2000, 78 percent of the county’s jobs were still wage-based (although there weren’t too many ranchers left).

Since 2000, though, the percentage of wage-based jobs in Teton County has fallen sharply, from 78 percent to 66 percent. As a result, today fully one-third of Teton County’s jobs are held by self-employed folks.

The fact that 34 percent of all Teton County jobs are held by entrepreneurs puts Teton County in the top six percent nationally. What’s really striking, however, is that, on a per capita basis, over the past ten years Teton County’s number of self-employed jobs has been the nation’s highest.

Unfortunately, the data don’t reveal the breakdown of those self-employed jobs by industry. But they do tell us that, in 2017, there were 0.48 self-employed jobs for every resident of Teton County. Meaning that, on average, if two years ago you weren’t working a self-employed job, either your spouse or your neighbor or your buddy was.

Given those numbers, it’s no surprise that efforts such as Silicon Couloir, Pitch Day, and other facets of our growing entrepreneurial ecosystem have been so favorably received. The market is clearly there.

Please support our work by donating to Charture through Old Bill’s Fun Run

To contact us, please call (307) 733-8687, or e-mail js@charture.org